Motherhood is hard. Make no mistake; this is a truth universally acknowledged amongst mothers of all stripes. Regardless of the philosophies of motherhood to which you subscribe, or the mama-circles in which you move, no other mother will question the enormity of the task to which you have committed. As feminist author Jessica Valenti puts it:

There’s a certain look that moms get that’s difficult to describe… all I know is that in the same way I can spot a heroin addict on the street, I can spot a mom. Caring for children leaves you haggard. (Believe me, I know— the under-eye circles I used to get after too many cocktails are now permanent fixtures on my face.) So I will not argue when someone says that mothering is hard.(1)

Contrary to popular mythology, I have never felt a single moment of judgment from women who have children in the same age group as my son.

Unfortunately, this consensus and camaraderie amongst mothers won’t stop everyone else from voicing their evaluations. As a mother, I’ve learnt this further universal truth: people are incredibly unkind to and judgmental of mothers. Whether it’s in the looks people give you whilst you’re fielding a very loud, very insistent supermarket meltdown, or the endless formula vs. breastmilk sittings of the peanut gallery, people love to judge mothers. The world revels in policing womanhood and it follows that policing motherhood is a natural extension of this. Keeping women preoccupied with our own faults and whether or not we’re making the best decisions possible for our children is a very good way of distracting from all of the ways in which mothers are still unsupported, underpaid and underserved by social structures.

This drives us into frenzied activity to ensure that we are doing the most we can and being The Best Mother Ever. We run ourselves into the ground daily, taking on the momentous everyday challenge of raising our children, and adding all of the additional trappings that we’re told make for good parenting. As Valenti says:

[…] good mothering is no longer just about raising well-adjusted kids. It’s about raising the smartest, coolest, artiest, most organic-eating, most well-behaved, and fastest video-game-weaned kids of all time. Whether you call them helicopter parents or CEO moms— there’s no doubt that “over-parenting” is everywhere and mothers are leading the way. They’re making their own organic baby food while scheduling piano lessons, ballet class, and French tutors. They’re spending all day online discussing the right kind of baby wrap and whether their DS or DD (dear son or dear daughter) is reading enough, rolling over soon enough, or could be getting any number of colds, flus, or viruses that are going around their neighbourhood. (1)

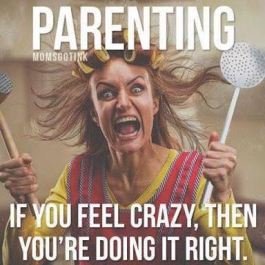

Popular discourse legitimises this by telling understandably frazzled moms that the bone-deep fatigue that results from this exhausting treadmill is completely normal. Which brings to the social media trend I like to call the #CrazyMutha.

I’m sure you’ve seen the memes: they depict a tired, hollowed-out husk of a woman with text explaining that she only looks and feels this bad because she’s doing it right. The message is loud and clear: if you happen to not exhibit these signs of extreme exhaustion and slight to moderate ill health, you’re not momming hard enough, and probably suck at this.

Some of the best moments in my life have been spent mothering my vivacious and energetic child. Some of the lowest, too. And whilst it’s true that many of my mothering moments – best, worst, and everything inbetween – have seen me looking and feeling like an exhausted mess, it cannot be said that my exhaustion and frenzy have made me The Best Mother Ever. If anything, the greatest lesson my son teaches me, is that we are both at our best in the moments where we stop trying very hard to be the Very Best to each other. We are at our bests when I am just me and he is just him. It’s a tough, ongoing lesson, with rich rewards.

A friend of mine rightly pointed out that the #CrazyMutha discourse is useful in that it acknowledges the truth that gets lost as our society pushes mothers to be Better, if not The Best Ever. We are tired. Some of us are clinically unwell. And it can feel affirming to see that difficult truth reflected back to us amidst a sea of Pinterest-perfect stock images of mothering. What feels less affirming is the message that your fatigue and possible ill health are a ‘normal’ state of affairs. Motherhood is hard and that is normal. Living with chronic anxiety and debilitating burnout are not. The inevitable fact of motherhood’s ‘hardness’ should not let society off the hook in terms of supporting and holding mothers up. In her excellent meditation on modern parenting and risk aversion, Zoe Williams writes:

If everything has an individual cause, you don’t have to sympathise with that mother whose child is disabled – she probably didn’t eat the right vitamins while she was pregnant. You don’t have to have fellow feeling when that child was hit by a car – that child should never have been outside the house, that child was unsupervised. You don’t have to feel for those parents whose child is self-harming or anorexic – they probably put it in nursery when it was too young, and are now witnessing the consequences of its cortisol levels. (2)

If we buy into this idea that the safety and success of a child is the responsibility of the mother (and she better be working her fingers to the bone to ensure both and be The Best Ever), we let go of the empathy necessary to build figurative and literal villages for all children. And those literal villages are those in which each child has access to quality healthcare and education, and is safe from harm, and well-nourished and cared for. By making these the sole responsibilities of mothers, we stop holding the necessary bodies – our state structures, the people who serve in our kids schools, the workplaces that will not grant us and/or our partners paid parental leave – to account and expect mothers to work miracles in social vacuums.

Is it any wonder we’re all so tired? Instead of this normalised debility and panic, I prefer a society that shows its gratitude to mothers and its empathy to all families and to children, by supporting mothers adequately. Once such a society is in place, we might all be a little slower to judge all parents, and a little quicker to empathise and lend what hands we can.

(1) Valenti, Jessica. Why Have Kids?: A New Mom Explores the Truth About Parenting and Happiness . AmazonEncore. Kindle Edition.

(2) Williams, Zoe. The Madness of Modern Parenting: (Provocations). Biteback Publishing. Kindle Edition.

Share this: