We all think the Creative Industries are an exciting place to work, but the recruitment and marketing messages we collectively send out don’t seem to be working, and still attract only a narrow band of people- as evidenced in the stubbornly slow changes in levels of diversity and gender imbalance.

Could the creative industries help their recruitment of new entrants by examining and manipulating the dynamics of motivation within young people, and revisit the language we use to portray our world to them?

In short, the general tactics of marketing and recruitment within the creative industries don’t really appeal any more to many young people- a sizeable proportion of tomorrow’s talent pool are no longer listening, and this should be of concern.

I believe well-meaning and aspirational messages can drive millennials further away from careers they could really thrive in and the companies they could enrich. However a possible solution may lie in applying what we now know of the science of motivation to our communication with potential new entrants.

Motivation: the ignored science?When I was at Creative Skillset, one of the issues with persuading people of the value of accreditation of university courses was what I called the motivation argument- basically “So-and-so went to (insert name of a course that hadn’t been accredited) and they were successful, ergo accreditation isn’t credible”

To me this highlights how game-changing motivation can be, and how it is valued. Exceptional talent can often power itself through the poorest of courses. One of the things good courses do is fuel the fire behind their students, but many individuals in less supportive institutions develop ways to light their own tinder.

These days we know a lot more about what some are calling the science of motivation, and yet we don’t use it to gain the talent pool we need.

As the creative industries we realise how important intrinsic motivation can be, and this is reflected in our recruitment strategies. “Come and earn a decent wage for reasonable hours and become financially secure” is not a refrain you see in adverts anywhere. Instead we almost celebrate precariousness by implication. Our message is often “its hard work, you’ll have to give 100%, but it’s really rewarding”. We assume this kind of message will enthuse young talent, and although for some it does, increasingly to today’s talented generation, this just won’t wear anymore. They have many other offers competing for their time.

We adults get the fulfilment of dopamine hits of intrinsic reward that keep us going, so we try to exhort young people in the same way. However, I’d suggest that our messages would have greater reach if we understood more about motivation and what drives young people.

Author Guy Standing talks about the ‘precariatised mind’ as a way to explain a new emerging class that is constantly faced with uncertainty. They are paralysed by choice and often scared of committing to any one path.

If we want to attract the best into the creative industries we need to promote the stability and reliability that creative roles can give. This means shifting the message from that of a chain of short contracts with different employers to one of the opportunity of a developing portfolio, but also a real transactional relationship that addresses young people’s psychological need for wellbeing.

One of the ways we unintentionally cut off supplies of talent to our industries is through our language. Here’s an example of how we try to appeal to young people, albeit from outside the creative industries:

“Don’t sit and watch the world go by. Change it” is the clarion call on a sign for the University of Essex as I pass through Colchester on the train. We’ll return back to this in a minute.

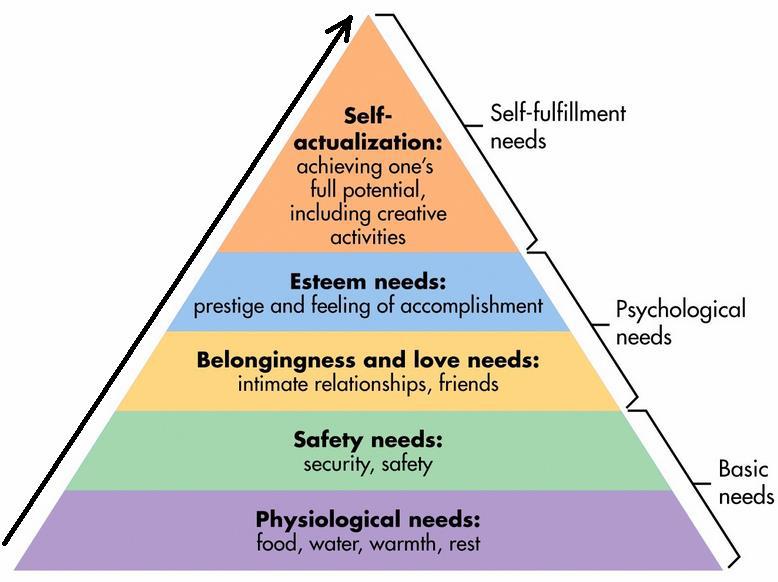

American psychologist Abraham Maslow (1908 – 1970) posited a five tier model of human needs, within a pyramid. The lower level needs must be satisfied before higher-order needs can influence motivation. Base needs of food, water, shelter need to be met, then safety of environment, health and shelter before moving up the layers to friendship, family, and only then self-esteem, respect and finally the peak of self-actualisation- creativity, problem solving and high order thinking.

I’m sure the University of Essex have done their research, but although noble and aspirational, world-changing will fail to stir the heads of those young people who are still worried about not achieving even the lower climes of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

The heady heights of self-actualisation and changing the world won’t appeal as much as the lower layers of Safety or ‘Belongingness’ to today’s ‘Generation Anxiety’, who expect they are destined for a life of debt and falling living standards. Maslow’s reassuring homeostasis of safety, wages and shelter will be more valued and craved by the new young precariat.

So often we try to appeal to lofty aspirations without understanding that the more prosaic and quotidian needs are what young people seek to fulfil. You can save the world, but if you’re still broke and can’t afford a social life what’s the point?

Our route to motivating students is often through dreams, and through the very adult concept of deferred gratification. Or even worse, through the profligate bandying around of the word Passion.

This may be true, but employers expect us to have passion for the most mundane jobs too these days

This may be true, but employers expect us to have passion for the most mundane jobs too these days

Passion is a busted flush. No matter how anodyne, lowly or dull your job role is you can bet somewhere in the job advert or job description is the exhortation that you must be passionate about, say, paperclip procurement or street sweeping.

Yet often we are surprised when potential new recruits don’t respond as we think they should. Young People read passion as a rather histrionic obsession of the adult world, a single-focus force which will cut off other options, or even disrupt the existing social bonds they’ve invested so much in. Unintentionally, recruiters are highlighting an example of loss aversion- students interpret passion as meaning they have to give up or let other pastimes atrophy; that they must leave behind social structures they have invested years in, for the all-consuming passion that the employer wants to propel them to happily work around the clock for.

They’ve had the P-word put in front of them so many times- they’ve seen it in so many contexts where the adult world tries to cajole them into decisions, that it is now viewed with suspicion.

We forget young people are continually bombarded with choices and offers, and having a passion in one area of endeavour is not a good tactic to them in the world of the gig economy.

Agencies like Creative Skillset try to motivate young people to fill skills gaps- it’s part of their role. It’s about supply and demand, not self-actualisation, but the two goals can often coalesce uneasily.

The Creative Skillset website is not unusual in using attractive video clips of creative professionals giving advice in order to attract and motivate new entrants.

“@REWINDco’s CEO tells us why personality, drive and enthusiasm is important to them” states one such article. Solomon Rogers is CEO of Rewind, and coming from a background in teaching, is a great communicator. In the video clip Sol gives solid advice for aspiring new entrants; “follow your heart …if you do the thing you love you will be successful… the second thing is to be dedicated to it, so if you want to do something give a 100%. If you don’t you will never get there. The final thing really is you’ve got to be a good person; being a positive person is the absolute key.” His advice is right from the heart, and designed to inspire.

It’s not that there’s anything wrong in Creative Skillset’s wish to inspire- but it does seem a pre-2008-financial-crash way of addressing young people. It speaks to the small percentage of young people who can afford to give 100% and not worry about practicalities like whether it’ll pay the rent.

Sol will undoubtedly and justifiably get the top percentile of talented driven individuals beating a path to his door. My point is that a re-appraisal of how young people’s motivations have changed over the last few years could mean a wider talent pool comes forward. If you have a family, a partner, a hobby or an equally powerful passion you can’t give the 100% that the Creative Industries seem to demand. That dilemma is even more acute if you don’t know what you love yet, or if you know you’re not always a positive person. Maybe financial services or retail will be better for you. They don’t want you to ooze passion or insist on 100% commitment. Working hours only will do, and they’ll also tell you what you’ll earn.

The science of motivation?

The science of motivation?

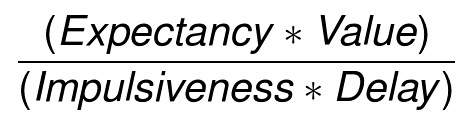

So what do we know about how people’s motivation works? Piers Steel is author of “The Procrastination Equation” and acknowledged as one of the foremost researchers on the science of motivation and procrastination. After analysing hundreds of studies on motivation, he came up with an equation that dissects motivation into its components:

M = E x V / I x D (Motivation = Expectancy multiplied by Value divided by Impulsivity multiplied by Delay).

It bears explanation. The important notion here is that high levels of motivation need high Expectancy and Value ratios while lower Impulsivity and Delay.

Expectancy? Think of this as Confidence. You have to expect that you can bring your goal to life. You have to think or ‘know’ it can happen. It’s the “I CAN DO THIS!” realisation.

The wonderfully alliterative Victor Vroom (1932- ) professor at the Yale School of Management, was responsible for expectancy theory. His 1964 book, Work and Motivation, is regarded as landmark in the field and states that if an individual believes he or she can do something then he or she is more likely to accomplish it. If someone does not think they are able to do a task, he or she is not likely to put much effort in. The resulting and predictable failure that ensues does not motivate a person to try in future.

Value is the level of desire or perceived meaning of any goal. This is the Spice Girls principle of “what I want, what I really, really want” (but in your case it might not be a ‘zigazig ah’). Desire needs to be very high to fuel our motivation.

Tweak those two variables upwards and motivation thrives. Conversely, two factors in our equation can pull us downward and corrode our intent.

Take Impulsivity. Can you focus your attention? Our young people are often called the the distracted generation. Of course, we are hardwired to be impulsive- but tempering this comes with maturity and adulthood. For young people this can be tough, meaning grappling with the anxiety of FOMO, or opting out of social networks. The more impulsivity, the weaker the level of motivation.

The last factor is Delay. Motivation is eroded by perceived temporal distance. Sometimes Motivation only kicks in when time is short- students cramming for exams for instance, after having months of prep time.

This equation can be useful if applied to the young people our industry wants to attract. Taking each of these components and addressing them in our communications can widen the talent that responds.

The lack of Expectancy is rife in young people. When we show examples of great inspirational creative work we have to take care that these potential recruits do not opt out because of low confidence. Also the rocket fuel of motivation – Value – needs to be raised, and this means promoting more of the things young people want in a job- a supportive social network, a community, trust, and a place where small incremental wins and encouragement can build their character.

Motivation’s head scientist Daniel H. Pink is the author of several provocative, bestselling books about business, work, and motivation, translated into 35 languages with more than 2 million copies sold worldwide. “I spent the last couple of years looking at the science of human motivation, particularly the dynamics of extrinsic motivators and intrinsic motivators… there is a mismatch between what science knows and what business does.”

Daniel H. Pink is the author of several provocative, bestselling books about business, work, and motivation, translated into 35 languages with more than 2 million copies sold worldwide. “I spent the last couple of years looking at the science of human motivation, particularly the dynamics of extrinsic motivators and intrinsic motivators… there is a mismatch between what science knows and what business does.”

I think we need to change tack on how we promote our creative industries. By recruiting with a less stakhanovite message, one that emphasises the social and the ability to treat creative work as a 9-5 job at first rather than a monocular all-consuming 24/7 passion, we might find we get a better response to our industry’s needs, and the quality of our new entrants increases too.

HR departments in particular might want to note Pink’s view that “a new operating system for our businesses revolves around three elements: autonomy, mastery and purpose. Autonomy: the urge to direct our own lives. Mastery: the desire to get better and better at something that matters. Purpose: the yearning to do what we do in the service of something larger than ourselves. These are the building blocks of an entirely new operating system for our businesses”.

An apt version of the famous “Success Kid” meme https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Success_Kid

Advertisements

Share this:

An apt version of the famous “Success Kid” meme https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Success_Kid

Advertisements

Share this: