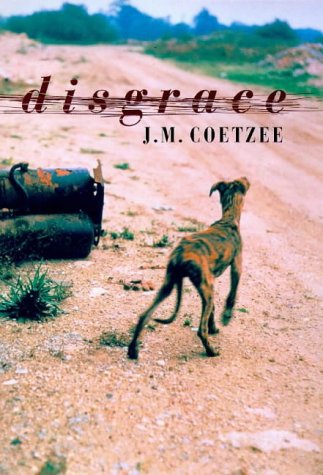

Even as my list of “New books to read” grows longer every day, I’ve recently found myself looking backward at novels that I could have read and wanted to read years ago, but never quite got to. One of those is J.M. Coetzee’s Booker Prize-winning novel, Disgrace. From the moment it was published, it got the literary world’s attention. I remember that. I remember how the reviews of Coetzee’s eighth novel were unanimously laudatory. I also remember how I was convinced at the time that it was a book I would find both riveting and very painful. I imagined Coetzee’s writing being focused and uncompromising, and knew that Disgrace was an important book. I wasn’t sure I could do it. I was younger, with younger children. The harshness and cruelty of the world affected me differently.

Even as my list of “New books to read” grows longer every day, I’ve recently found myself looking backward at novels that I could have read and wanted to read years ago, but never quite got to. One of those is J.M. Coetzee’s Booker Prize-winning novel, Disgrace. From the moment it was published, it got the literary world’s attention. I remember that. I remember how the reviews of Coetzee’s eighth novel were unanimously laudatory. I also remember how I was convinced at the time that it was a book I would find both riveting and very painful. I imagined Coetzee’s writing being focused and uncompromising, and knew that Disgrace was an important book. I wasn’t sure I could do it. I was younger, with younger children. The harshness and cruelty of the world affected me differently.

Such was my impression then. Reading Disgrace when it was first published in 1999 must have been an intense and destabilizing experience—especially for the author’s compatriots— coming a mere five years after the end of apartheid in South Africa. With his beautiful, elegant book which asks so many uncomfortable questions, J.M. Coetzee dared to shine an unrelenting light into the dark areas of South Africa’s cities, its countryside and into the psyches of the novel’s readers.

Since then, Coetzee has received the Nobel Prize in Literature (2003), and South Africa lives with the challenges of fulfilling the promise of a post-apartheid society. The world has moved on, these past twenty years, and it’s a change that has all but wiped South Africa and the leadership of Nelson Mandela from our minds. It’s disgraceful, and inevitable I suppose, as time marches on and human beings still struggle to learn the lessons of history. South Africa’s great democratic leap forward was followed by Arab springs, by war, civil unrest and famine sweeping through Northern, Eastern, Central Africa and the Middle-East, and more recently, by the rise of the far right in Europe and North America and the Black Lives Matter movement.

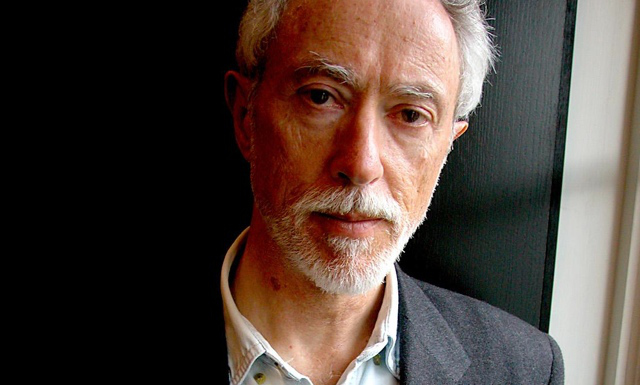

Author J.M. Coetzee

Author J.M. Coetzee

It’s in this context, with a new generation now populating the planet, that I finally read Disgrace. In fact, I finished it just a few days ago. I wonder if it isn’t the times themselves that drew me to the title, to the word DISGRACE, which seems so tragically appropriate now. It was a different book than I expected. Not quite as painful. Not as cruel. More complex and just as thought-provoking as I thought it would be. I won’t review it for you; the very best review of the book I’ve read was published in the New York Times twenty years ago and says everything about the novel that I would say if I wrote as well as Michael Gorra. Disgrace is a masterful work of fiction.

I’m a different person now. I saw different things in the novel. These are years that have brought writers like James Baldwin back into the light, and seen the emerge of many voices, like those of Ta-Nehisi Coates, Colson Whitehead, and so many others; and I write this aware how little I know of African literature, and the voices I haven’t yet read.

I’m an older person now, and was perhaps better able to make sense of a character like the novel’s protagonist, David Lurie (a patronym that suggests something shocking and distasteful about him, I think) : one of those disquieting, older male characters—Lurie is in his early fifties— who walk around in novels in a fog of impending irrelevance, a chronic state of disoriented melancholy, as though, like aging lions, they have never considered coming to terms with the idea of life beyond one’s prime, and of mortality. He reminded me of Dr. Frank Sina, in Vassanji’s Nostalgia, and also a little of Jonathan, in Neil Jordan’s The Drowned Detective. I thought as well of Tony Webster, in Julian Barnes’ The Sense of an Ending.

I’ve also had twenty more years to observe the horror of rape as a weapon of individual dominance and violence, and as a weapon of war.

I’ve also had twenty more years to observe the horror of rape as a weapon of individual dominance and violence, and as a weapon of war.

In his brilliant review of Disgrace, Michael Gorra compares and contrasts the work of South African writer Nadine Gordimer and J.M. Coetzee:

“Gordimer is expansive where Coetzee is spare, and if her sentences are often knotty and elliptical, she nevertheless remains committed to a kind of social realism. Coetzee’s prose has, in contrast, an accessible ease that belies the slippery nature of his work as a whole. Each is a gambler, but they’ve staked their careers on different games: Gordimer so timely that she risks obsolescence, Coetzee so determined to avoid a fiction based on what he has called ”the procedures of history” as to chance his own irrelevance.”

It’s unimaginable that writing as powerful as this could become obsolete. It’s up to the reader to make the adjustment, and to try to see where literature fits on the broader canvas. Anything else would be a disgrace.

Advertisements Share this: