I bought and began reading the first volume (This Earth of Mankind: (Bumi Manusia in Bahasa Indonesian, the national language) of the Buru Quartet by Indonesian novelist, Pramoedya Ananta Toer (1925-2006) in the Jakarta airport. It was spellbinding. It would have had to be to take me away from the blooming, buzzing confusion of the Garuda departure lounge!

There is a whole lot of soap opera and colonial injustice in the first two volumes (Child of All Nations is the second). By the third, Footsteps (Jejak Langkah, fkrst published in 1985), Minke has left medical school and become a fulltime anticolonialist journalist and activist. At the end of the volume he is exiled to the distant island of Ambo and denied any contact with his business, personal, and/or political confederates on Java. Footsteps largely buries Minke’s story under political intrigues.

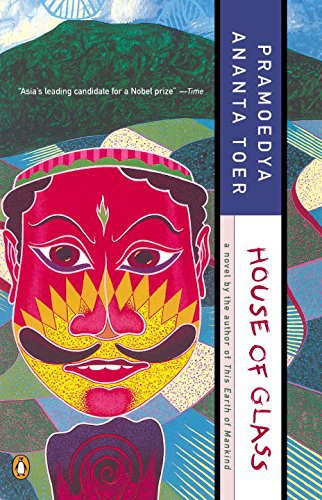

The narrator of House of Glass (Rumah kaca, first published in 1988) is Jaques Pangemanann, a Catholic Menadonese (native but not Javanese) who rose to be the first native police commissioner and moved to the secret police as the expert formulating tactics to prevent nationalist awakening and the consequent anti-colonialist agitations. Educated at the Sorbonne, married to a French woman, and of higher official position than almost all the Europeans in the government of the Dutch East Indies, Pangemanann not only recommended exiling Minke, but also accompanied him into (internal) exile. Moreover, Pangemanann has the manuscripts of the three volumes of Minke’s memoirs and has studied them closely (better to understand the threat of awakening consciousness of failure of the colonial regime to live up to its avowed principles or even its laws, plus Minke was in touch with a Chinese nationalist and of Japanese and Filipino nationalist self-assertions).

Pangemanann is a complex character, painfully aware of the system’s racism, exploitation, and shirking of any “civilizing mission.” He seems to me preternaturally (which is to say unbelievably) aware of “contradictions” in the colonial system and of the tide of history (awakening nationalism in Asia and offshore islands) and in his narrative analyzes events in the framework of a late-20th-century (which is to say anachronistic) perspective.

Pangemanann clings to power, even as his family implodes. He has no friends and is greatly resented by his bosses and by his compatriates. Like Europeans going to pieces in the tropics, Pangemanann takes heavily to the bottle. Despite being incapacitated by illnesses and by plain inebriation, Pangemanann keeps his footing in the slippery bureaucracy, and succeeds in hobbling the organization Minke left behind.

Though Pangemanann is a rounded character, his plight and effective manipulation of potential dissidents does not seem to me to support a 384-page novel. Minke does not return from exile until page 296, his mother-in-law (the most riveting character in the first two volumes) later still.

I am confident that very few Anglophone readers have the key(s) for the account of incipient dissident activity and leaders on Java in the first two decades of the 20th century. As characters in a novel, only one of them (a woman) makes much of an impression (on Pangemanann or on the reader!).

House of Glass could be read as a modernist novel about the unraveling of an official whose life is acute bad faith —insofar as he is betraying his own people, Indonesians, to maintain exploitative and condescending Dutch rule. If religion rather than point of origin was the basis for his identity, Pangemanann was not betraying “his own kind,” acting for the interests of the Christian aliens against the Muslims of Java, but Pangemanann constantly sees himself as a “native,” mistrusted by the Dutch even more than by the Javanese, most of whom hope he might be a patron or mediator with the Dutch for them. The basis for allusions to Minke and his trilogy of memoirs do not need to be understood to follow the plot of House of Glass. But I think that This Earth of Mankind and Child of All Nations are more gripping narratives, reasons other than beginning at the beginning not to plunge into House of Glass.

In that the books were banned until Suharto was finally overthrown, at the back of my mind while reading the Buru Quartet was “What’s subversive here?” The whole quartet takes place before 1920. The injustices are those of the European colonizers, not of the post-colonial kleptocracy. Minke is a nationalist (and Pangemanann thinks of the Indonesian people and even colonized people as a “we” to which he belong) and Suharto came to prominence fighting (very ineffectively it must be granted) the re-establishment of Dutch colonialism after Japan surrendered control of Indonesia.

I guess that consideration of the functioning of secret police manipulating dissent was not something the Suharto autocracy wanted exposed, even if it was a past and enemy regime.

Supposedly, the Buru Quartet was first told to fellow prisoners at the remote Buru island prison. The complexity of the earlier volumes made me question how much the text could correspond to oral composition/recitation (mindful that the very long Ramayana and Mahabharata are the staples of Javanese puppet theater). I find it even more difficult to imagine prisoners being interested in the details of the disturbed life and nefarious activities of a colonial official in the 1910s. But there is not any of the class analysis that might have alarmed Pangemanann successors in the Suharto regime in Child of All Nations and the nitty-gritty of organizing protest groups in Footsteps.

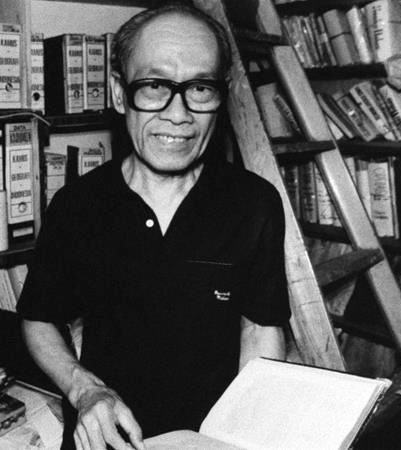

Pramoedya, who had earlier been imprisoned by both the Dutch and the Sukarno regimes, was imprisoned without being charged with any crimes from 1965 to 1979 and held under house arrest until 1992, banned from publishing (in the early years doing hard labor, he was denied writing instruments). Sympathetic as I am to a writer persecuted as Pramoedya was, I don’t think that House of Glass is as compelling a novel or interesting a document as This Earth of Mankind or The Fugitive, or his own quasi-memoir, The Mute’s Soliloquy.

© 2017, Stephen O Murray

Advertisements Share this: