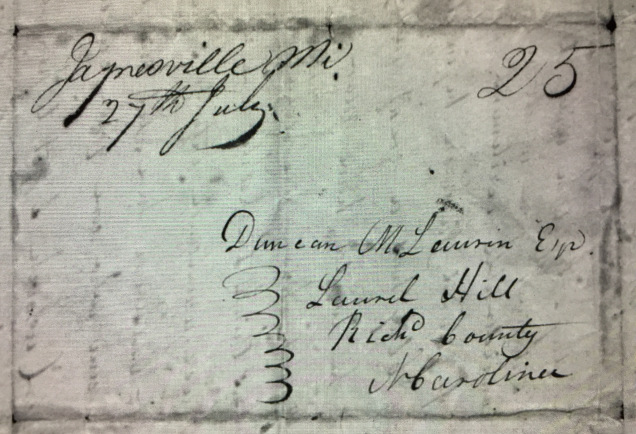

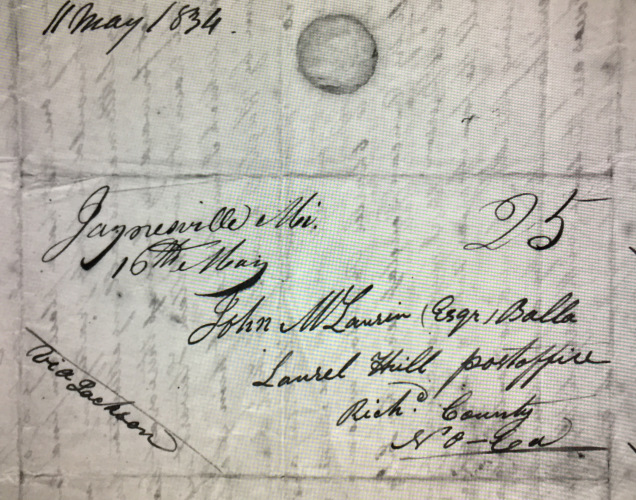

This letter was addressed in July of 1831 and sent from the Jaynesville, MS post office to the address in North Carolina with the appropriate 25 cent postage whether prepaid or paid upon destination. The paper has been folded and sealed to create an envelope-like space for the address.

This letter was addressed in July of 1831 and sent from the Jaynesville, MS post office to the address in North Carolina with the appropriate 25 cent postage whether prepaid or paid upon destination. The paper has been folded and sealed to create an envelope-like space for the address.

The following is the first of a group of posts highlighting the content of Duncan McKenzie’s correspondence from Covington County, Mississippi with his brother-in-law, Duncan McLaurin, in North Carolina during the decade of the 1830’s. Each post will examine a different topic addressed within the letters.

During the decade of the 1830s it cost twenty-five cents to mail a letter of one sheet a distance of more than four hundred miles – a high price for most farming families, especially those living great distances from relatives left behind in the east. For example, a U. S. laborer in the early 1830s might have made an average of seventy-five cents to one dollar a day. According to The Postal Age: The Emergence of Modern Communications in Nineteenth Century America by David M. Henkin, in the 1830s the bulk of the mail included subscription newspapers, which enjoyed lower rates of delivery. One has only to peruse the long lists of names posted by the Post Office that appeared in the newspapers of this decade to appreciate the difficulties of retrieving one’s mail. If it arrived at the post office in a timely manner, it was likely to take weeks for the busy rural farmer to have time to negotiate the distance to the post office. In addition, this farmer would likely have to pay the postage in order to put hands on his letter. In 1830 the requirement of prepaid postage, reduction in postage, and the use of government issued stamps was still more than a decade coming.

The mail, despite the increased upkeep of the roads, traveled slowly at best by today’s standards, a month or more in passage was not uncommon. Most mail traveled by horseback or stage on roads, the passage upon which was uncertain due to weather conditions. Also, mail was sent via boats on the rivers, also subject to the danger of snags and varying river stages. Many people avoided using the postal system and still sent letters and packages by way of traveling friends and acquaintances, when available.

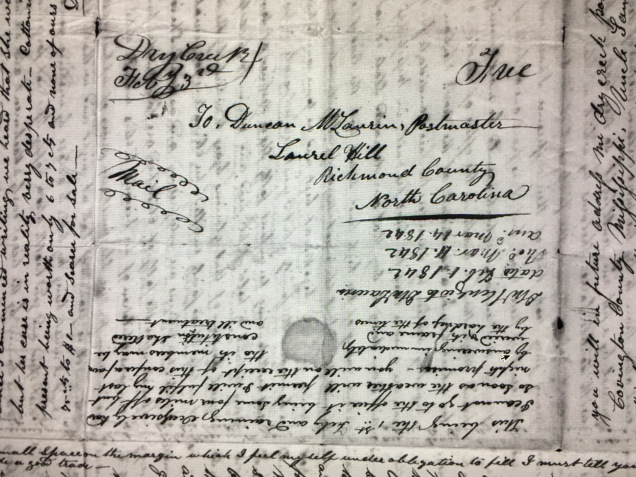

Every part of Duncan McKenzie’s letter is filled with writing, even the margins. So little space is left on this page that Duncan McLaurin was forced to write his date of receipt notations on the address portion of the page. The postage is marked free on this letter because Duncan McLaurin was serving as postmaster at Laurel Hill and had evidently invoked franking privileges.

Every part of Duncan McKenzie’s letter is filled with writing, even the margins. So little space is left on this page that Duncan McLaurin was forced to write his date of receipt notations on the address portion of the page. The postage is marked free on this letter because Duncan McLaurin was serving as postmaster at Laurel Hill and had evidently invoked franking privileges.

In perusing the Duncan McLaurin Papers, it is clear that one sheet created four writing surfaces, and often writing was continued up through the margins of the paper. After all, with mail delivery as expensive as 25 cents a sheet, one could not afford to waste any space. The paper was folded to form an envelope of sorts, which was sealed with wax and upon which the address was written directing the letter to a particular post office. If the letter had been sent by mail the number 25, for 25 cents postage, would appear in the corner, where today a stamp would appear. Mapping postal routes did not begin until around 1837, so especially rural letters, would not bear a street address. Mail was not delivered directly to the home, but had to be retrieved from the nearest post office, which might be someone’s home or a local business. Some of Duncan McKenzie’s letters to his brother-in-laws, Duncan and John McLaurin, bear the 25 cents postage, others do not. Those letters that do not bear the 25, have likely been carried by friends or family members traveling from Covington County, MS to Laurel Hill, NC and directly put into the hands of the person. Sometimes the name of the person charged with delivery is written on the front of the letter.

In 1837 Duncan McKenzie receives a gun he has asked John McLaurin to purchase for him from a reputable gunsmith in Richmond County, such as Mr. Buchanan. The gun is for his older boys, who love hunting and tracking animals in the pine woods of Mississippi. However, it takes nearly a year for the gun to be sent by way of a traveling friend, relative – or someone trustworthy. It took another length of time for Duncan McKenzie to retrieve the gun in Mississippi, because it was delivered to the home of an acquaintance miles away.

In his March 21, 1837 letter, Duncan McKenzie reports to Duncan McLaurin, “I also heard that the gun came — I forward this to you per Mr. John Gilchrist who is on his way to No-ca … he promises to call at your village.” Evidently, this particular letter will not need the 25 cent postage. In this same letter, McKenzie wishes to let his father-in-law know where to direct a letter to a relative in Mississippi, “…to Aunt Catharine Dale Ville po – Ladderdale (Lauderdale) Co. Mi.” In his next letter, a month later, Duncan McKenzie has still not retrieved the gun, “we have not brought the gun down from Mr. McCollum yet tho only 7 miles.” Seven miles does not seem so far, but to a busy farmer and over uncertain roads, life was just not that convenient.

In the letter of April 1837 McKenzie remarks that his letter will be mailed at Mount Carmel since he will be going to vote in an election for a member of the state legislature. It was probably common practice among those who attempted to write regularly to have their mailings coincide with trips to a nearby post office. Indeed the post mark reads Mt. Carmel with the number 25 in the stamp’s corner.

In the western states such as MS, news from families in the east was of such importance that letters were commonly shared and sometimes purposely passed around the community. McKenzie mentions to his brother-in-law that he had read a letter in which he discovered that a valued mutual friend in Carrolton, MS was in bad health with chills and fever. In 1839 Duncan McKenzie writes that, “Having written so lately to John I do not know what to add more without repetition.” Obviously, Duncan and John McLaurin shared news of their sister’s family with every letter.

The circle at the top of the address portion of this letter is evidence of the wax seal placed on the page after it is folded.

The circle at the top of the address portion of this letter is evidence of the wax seal placed on the page after it is folded.

In spite of the precarious nature of the mail delivery during the first half of the 19th century, it was probably more successful than it was not. An example of the concerns that correspondents from west to east harbored each time they used the post are evident in the following comment by Duncan McKenzie of Mississippi to his brother-in-law in North Carolina. In an earlier letter he had mentioned that McLaurin’s sister, Barbara, had not been feeling well. Further information on the matter seems to have been lost in the mail, causing some anxiety. It turned out that Barbara’s complaint was a pregnancy and by the time the issue was sorted out, the baby was very near birth. The following is from McKenzie’s November 1838 letter:

“…my letter of the latter part of Augt.

had not reached,, you before the date of 7th Octr

If it miscarried I beleave it was the first lost

between us in near Six years regular correspondence

The receipt of that letter in due time, I know

would have been to you a Source of some joy, at least

it would dispel the uneasiness that the marginal notice in my letter of the early part of June gave

of Barbras situation — But if need be the treach

-erous or negligent hands who were the cause of the

delay or final miscarryriage of a letter which was

to me a Source of inexpressible pleasure to have

Through the mercy of our kind heavenly Benefac

-tor to communicate to you its contents, who I know

would have received its contents with joy and Thanks

-giving to the dispenser of all mercies to his creation,

I hope my letter to John of October has not been inter

-cepted, for fear that it did not reach you I will give Some

of the contents of both in this and mail it at Williams

Burgh our county Sight”

In this letter McKenzie also mentions the birth of his daughter Mary Catharine and the territorial conflict between local postmasters that he thinks may have been a contributing factor in the miscarried mail. He tells Duncan to continue use the Jaynesville post office as usual if the letters, in reality, have not been lost. If they have, he should send his mail to nearby Mt. Carmel.

Sources

Garavaglia, Louis A. To the Wide Missouri: Traveling in America During the First Decades of Westward Expansion. Westholme: Yardley, PA. 2011. 59

Henkin, David M. The Postal Age: The Emergence of Modern Communications in Nineteenth-Century America. University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL. 2007

http://libraryguides.missouri.edu/pricesandwages/1830-1839 . accessed 3 January 2018.

Letter from Duncan McKenzie to Duncan McLaurin. 21 March 1837. Boxes 1 & 2. Duncan McLaurin Papers. David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Duke University.

Letter from Duncan McKenzie to Duncan McLaurin. 7 November 1838. Boxes 1 & 2. Duncan McLaurin Papers. David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Duke University.

Letter from Duncan McKenzie to Duncan McLaurin. 14 August 1839. Boxes 1 & 2. Duncan McLaurin Papers. David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Duke University.

Share this: