Times were never simpler.

We like to think of the past as “simpler times,” something that is often used to make a joke and a slight wince in memory of how things used to be. But there has never been a time in human history where scandal, corruption, greed, and fury have not penetrated the mass existence. There have only been times when the envelope had not yet been pushed.

Glancing back to the turn of the 20th century, from approximately 1900 to about 1920, modern day Americans would generally think of this era as being fairly clean cut, simply based off assumptions and stereotypes from books, film, and the long ago history class.

It was a time where modesty was king; where women’s role in society existed solely in the home and their ability to keep birthing; where men were ‘gentlemen’ and the word ‘divorce’ never uttered. Times were simple, peaceful, quiet, especially in an age that lacked the sophisticated technology and advanced forms of communication we have today that allow for the constant internal and external chatter.

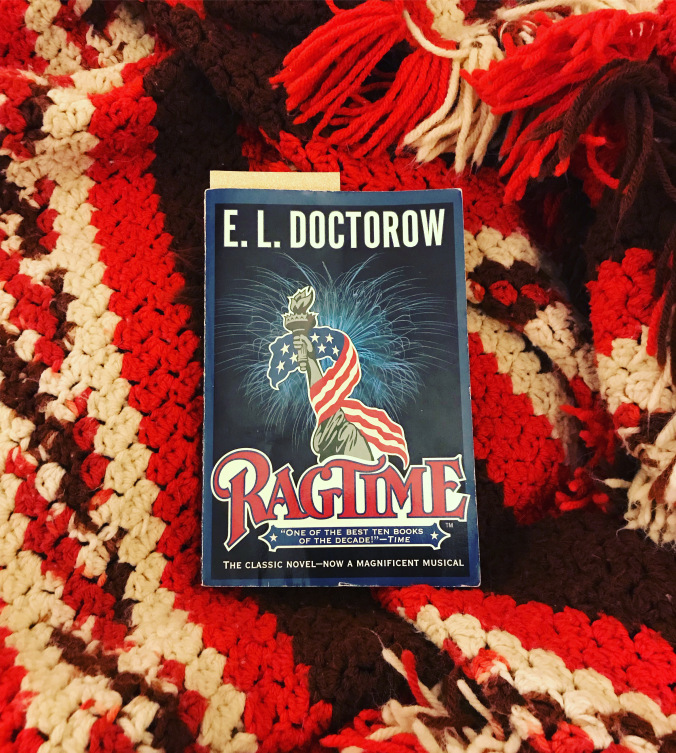

This was my own assumption of what I believed E.L. Doctorow’s novel, Ragtime, would be about, especially once I learned it had been adapted to a musical. Only pleasant, clean novels are made into family friendly musicals, right? Right?

I was over the moon to have never been so wrong about a novel before in my life.

This novel, incorporating several historical figures into its plot and set in the first two decades of the 1900s, proves that these years were not simpler than today. They were just as corrupt as today. They were filthy, diseased, narcissistic, abhorrent, and absolutely delightful.

I can’t, for the life of me, tell you exactly what the novel is about, but its elegant prose, condensed into tiny, staccato sentences, is like being punched in the gut by a beautiful poem; lyrical in its sound and brutal in its truth.

The novel centers around a small family simply referred to by their familial titles- Mother, Father, Younger Brother, and the Boy (the son)- as they live their lives in New Rochelle, New York, interacting with famous figures from their time, including Harry Houdini, Henry Ford, and Emma Goldstein. I loved this ambiguity of not naming the characters.

It’s a remembrance of all the unnamed people who came before us who experienced the historical events outlined in the text and who interacted with all the historical figures we met in the story; the footmarks of history who did most of the birthing and breathing and living and dying in this century, the ones we never hear about.

Even more telling is the way the text is actually written. Doctorow abandons quotation marks and separate line structure for his dialogue, allowing instead what was said to blend in with the rest of the story. What is said blends with what is told; blurring of history and legend.

My only two complaints about Ragtime have to do with the length and the ending. The last 50 or so pages probably could have been omitted. They tend to drag on without offering anything to the overall plot. And as staccato as the descriptions, so is the ending abrupt and anti-climatic. It left me with a resounding, “Oh” and flipping the last few pages to make sure I didn’t miss anything.

But perhaps this is indicative of history, of past and future lives, of our lives. When we look at the musical definition of ragtime, the “meter” of a ragtime is not as slow as a march but not as fast as a waltz. Rather, it is an accentuation of the beat, allowing the listener to move to the music, to allow everyone to be a part of the song and of the history that they’ve touch.

Even those without a name.