What I watched: The February 1, 1949 episode of Howdy Doody. This episode would have aired in the afternoon on NBC, and is available to view on YouTube. The episode starred “Buffalo” Bob Smith as both himself and the voice of Howdy, with Bob Keeshan as Clarabell and E. Roger Muir directing.

What happened: As usual, Buffalo Bob opens the show wearing a weird safari hat and leading the assembled children in song. This is immediately followed by another song — “Shout Howdy Doody”, about how you can and should instantly make friends with someone by shouting “Howdy Doody” at them when you meet them. Bob goes over this concept at length with the Peanut Gallery, being very instructive on the powers of this special codeword, which is so much more potent than a normal greeting. It has the air of a cult recruitment ceremony, but less exciting.

Howdy hands out six drawing cards to kids, all part of some plan he has to demonstrate the meaning of friendship. Having somehow spent ten minutes on this, it’s time for the film segment. After a momentary gag where the film is broadcast upside down and fixed by the magic words of “Howdy Doody”, we settle in for another viewing of a Mr. Smith silent comedy, featuring somewhat deadly family dysfunction. This one is set unseasonably at Christmas, with a rich prospector uncle coming to visit from Texas. There aren’t really a lot of jokes. Buffalo Bob’s narration, in trying to explain to kids why these events are funny and not just upsetting, often sounds like the detached rationalizations of a serial killer. “Well, isn’t that awful” he says, followed by a knowing chuckle.

Howdy Doody’s Final Repose.

Howdy Doody’s Final Repose.

When we come back from the segment, we see what Howdy has concocted. The children have all received instructions to draw one image, but when combined they have unknowingly created a narrative, that of Little Red Riding Hood. Scott McCloud would probably have a lot to say about this. Things don’t exactly go perfectly. Bob gets a little girl from the audience to reveal the story, but she can’t follow it, mistaking the big bad wolf for Clarabell. (Clarabell is, I must reiterate, a terrifying clown.) I don’t blame her — most of the images are just of characters, without actions. Then again, what do you expect from little kids drawing an out-of-context clue while watching a movie? Howdy has a very strange reaction to this, lying back and muttering “I’m dead, Mr. Smith” — which seems, uh, out of character for this show’s sense of humour.

This acrostic meme is really played out.

This acrostic meme is really played out.

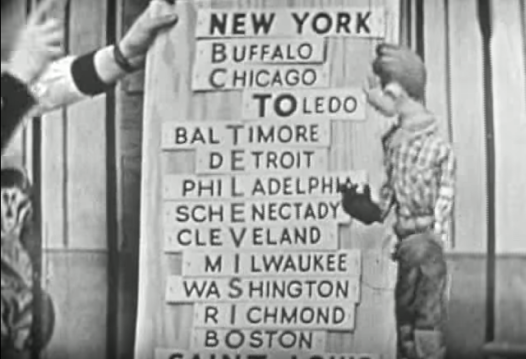

As a final demonstration of what individuals can accomplish through working together, Howdy presents an acrostic of all the cities that NBC broadcasts TV to, including such metropolises as Schenectady and Toledo. Together, albeit with a little fudging, they spell out “NBC TELEVISION”. Whenever there’s a mystery in Howdy Doody, the solution is probably a cheap plug. With that, the episode seems to have improbably run long, and Bob and Howdy have to sign off without a closing song.

There are eleven more years of this, guys.

What I thought: Even by Howdy Doody’s standards, this episode was pretty insipid. There doesn’t seem to be much of a concept to it besides a lecture on friendship, and a strange insistence on “Howdy Doody” as some kind of magic friend-making word. In the manner that would become characteristic of children’s shows, this lesson combines simple moralizing with commercial exploitation. Children might make more friends by engaging with their friends in an enthusiastic manner, but they’ll also be spreading the brand name everywhere they go. And they’ll also be identifying themselves as viewers of Howdy Doody, using an expression that will hopefully find recognition in other viewers of the show.

This was one of the innovations of Howdy Doody. It was perhaps the first television show to imagine that it had an audience, and that this audience would have a coherent identity. When Bob Smith referred to the “Peanut Gallery”, it wasn’t just the studio audience, but also the children watching on television — who he continually addressed and welcomed. There’s even the strange pretense that he can see and hear the children tuning in, and their imagined reactions. Smith’s way of talking to this audience was condescending, but it did recognize them as an audience constituted by joint spectatorship — what Michael Warner would call a public. And, if they followed his instructions to the letter, they would go about expressly labeling themselves as members of this group, repeating the name of the show as an incantation. This audience may have been more phantasmal than real — while Howdy Doody was one of the most popular shows on television, TV owners were still a small minority. But Smith and Muir, if nothing else, understood the cultural and commercial potential of creating such an audience.

If there is any joy in this largely didactic episode, it comes from the most common source of joy in early television: things going wrong. The audience’s heavy involvement is frequently a problem for Howdy Doody as much as it is an asset, as small children often freeze up or have unpredictable reactions. This is no more true than in the case of the little girl brought up to attempt to recognize the story of “Little Red Riding Hood”, who quite reasonably can’t make sense of six hastily-executed child’s drawings. This ends up undermining the point about how people can accomplish things together, to Bob Smith’s visible annoyance. He spends such time trying to get her to say what he wants her to say that, in the true sign of a messed-up production, the show that had earlier seemed to be stalling for time ends up rushing at the end. That’s the thing about publics, I suppose: they’re never quite as easily manipulated as you want.

What else is on?: DuMont aired programs by the names of The Ted Steele Show and Children’s Records, while New York independent WPIX aired Comics on Parade, Pixie Playtime and Magic Books. These attempts at capturing Howdy‘s young audience were largely unsuccessful.

Coming up next: Sid Ceasar and company kick off the variety crazy with Admiral Broadway Revue.

Advertisements Share this: