By Ru Freeman

You can buy A Curious Land by Susan Muaddi Darraj at your local bookstore, Barnes & Noble, and Amazon.

You can buy A Curious Land by Susan Muaddi Darraj at your local bookstore, Barnes & Noble, and Amazon.

Taxi drivers the world over exist in possession of one liners that summarize all manner of things: circumstances, politics, personalities, conditions, and relationships. They neither hoard their wit nor dispense with it freely. If the moment strikes, they share, if it does not, they keep their counsel, knowing that the opportunity will present itself. They were masters of the 140 character mindset long before Twitter came into existence. At the very end of Susan Muaddi Darraj’s A Curious Land: Stories from Home, a taxi driver carrying Adlah Muneer Miltner to a Ramallah hotel from Ben Gurion Airport, is even more succinct: “Everything changes, nothing changes.”

I was struck by these simple words because they reminded me of the most enduring impression I had of Palestine and Palestinians from my relatively recent time there: they were indomitable.

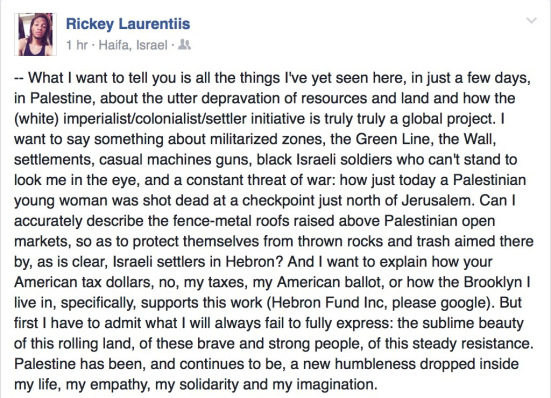

How could that be possible? Whether we go back to their history before Alexander the Great, who invaded Palestine in about 330 BC, or to the time in 1187 after Saladin’s forces defeated the crusaders, or to the Ottomans in 1486, Palestinians have had to undergo centuries of invasion and occupation, the latest, and most inhumane being from the Israelis, a form of oppression perfectly enunciated in a post by American poet Rickey Laurentiis, upon his first visit to that country.

In the hundred years covered by this collection alone, the Palestinian people, from the bedouin to the villagers in A Curious Land’s Tel al-Hilou have to contend with the presence of Turks, Brits, Egyptians, Syrians, Jordanians, and of course, Zionists. And yet, through it all, whether they stay and fight for their homes or carry their families to safety through the night, the men still gather at the qahwah, the young still dream of love and professional success, parents shoulder burdens, marry their offspring, and bury their young and their old. Gossip flows through the towns, stories are passed along like diamond chips—brilliant but flawed—Arabic (never Turkish) coffee is cupped in veined hands, prayers are said, pledges made, and life goes on. It is the sublime ordinary that we yearn for in our heart of hearts.

The author in the perfume shop in Nablus

The author in the perfume shop in Nablus

In Nablus one day I was passing by a row of shuttered shops when I saw one wooden door open. I peered into the brightly lit sliver of a shop that lay behind it, a perfumery. It was like the stage set to a play I might be fortunate enough to see. A young man in a red shirt was milling around in the back while two old men perched on stools nearby and chatted with him. I entered the store, a magpie lured to bright things; my mother had been a lover of perfume, and I had inherited the craze along with her collection when she passed away.

None of the men look up or pay me any heed, foreign though I clearly am, in appearance, in demeanor, in dress. I take the opportunity to touch the small bottles lining the walls, to let intoxication in. After a while, when it is apparent that I might actually want to buy something, the two older men direct the young man’s attention to his potential customer, gesturing with their heads, and leave. The proprietor does not ask me what I want to buy, instead we fall into an easy conversation about the lure of perfumes. How irresistible they are, their many composite parts, the origins of those ingredients, the places where the best perfumes are created. Do you like this one? How about this? We spend a long time doing this, as though he and I are old friends traveling through strange lands, out to discover the best among the best to indulge our senses. He points to a row of perfumes up on a high shelf. “These I will never sell. They are for me,” he says, his own collection. And yet, after more time passes, more scents and stories shared, he returns to them and takes one down, his favorite. He applies the tiniest smear on my wrist. The smell of rose, neroli and Florentine orris rises up to my face and he grins widely at my delight and he picks another one to wave under my nose: oud, orchid, orange; a third: black pepper and patchouli.

Bottles in the Nablus perfume shop

Bottles in the Nablus perfume shop

Later, as he wrapped two tiny vials of perfumed oils that he mixed for me, each chosen according to what he has learned about my preferences, sealing them with the utmost care, his hands careful, intent, we talked of our families. I told him about my writing, and he propped my business card next to his row of precious not-for-sale perfumes. “Consider Palestine your second home. You are welcome here,” he said when I told him I had traveled from America. I heard about his wife and son, and imagined him returning safely home to them, the fragrance that they must associate with his work and his obsession.

How much time all this took, I couldn’t say. It might have been only half an hour, much less, more. But it was also a lifetime. A moment that framed my decades of distant involvement with a country to which I can only lay the claim of a global citizen who believes that the plight of others is her responsibility. I can still see him standing there, tall and fair, handing over the perfumes which, though I have paid for them, feel like a gift. In a place where their lives are always under threat, always being subjected to relentless deprivation, where despair is distilled and force-fed in every way possible, Palestinians act like coal in deep mines: they turn themselves into diamonds, a strength so great that the only thing that can threaten it is another diamond. Faceted, brilliant, sharp enough to cut but choosing whenever possible to dazzle. And it is these kinds of moments that affirm that sense I have: they will prevail. That in Palestine, one is never owned by hours and minutes, that “there is always time for a chat, to boil a small kettle of tea.” That this is the home I miss, and that I looked for and created wherever I went. A feeling that is the essence of all human longing, but manifested with the utmost clarity in Palestine.

A thin unbreakable thread weaves through Darraj’s stories affirming this indelible fact of community. Where memory is preserved about essential things—which mother threw herself over the body of someone else’s son and claimed him as her own to prevent him from being killed by Israeli soldiers; which secret-keeping spinster carries love notes between the homes of two teenagers while Israeli soldiers demand their food at gunpoint and empty their urine and shit into their water well before they give up the occupation of their roof; which wounded man’s lineage can be traced through exile and return, in Guatemala, Kuwait, and Washington DC; which love is lost and which held even after death and which altered by which grateful immigrant. A village rises up once more out of the earth, water fills the empty well, the Virgin Mary at the top of the church is unsullied by bullets. Erasure is not permitted. It is never permitted. How glad that makes me.

Ru Freeman is a Sri Lankan born writer and activist, the author of the novels A Disobedient Girl and On Sal Mal Lane, and the editor of the anthology, Extraordinary Rendition: (American) Writers on Palestine, a collection of the voices of 65 American poets and writers speaking about America’s dis/engagement with Palestine. She holds a graduate degree in labor studies, researching female migrant labor in the countries of Kuwait, the U.A.E, and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and has worked at the Institute for Policy Studies in Washington, DC, in the South Asia office of the American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL/CIO), and the American Friends Service Committee in their humanitarian and disaster relief programs. She is a contributing editorial board member of the Asian American Literary Review, and a fellow of the Bread Loaf Writer’s Conference, Yaddo,Hedgebrook, the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts and the Lannan Foundation. She was the 2014 winner of the Janet Heidinger Kafka Prize for Fiction by an American Woman.