This is a repost. But I never get sick of these poems. And many of my students and colleagues might need some inspiration this time of year.

Pindar, Isthmian 7.40-49

“Seeking whatever pleasure each day gives

I will arrive at a peaceful old age and my allotted end.

For we all die the same, though

Our luck is unequal. If someone gazes

Too far, we are too small to reach the bronze threshold of the gods.

This is why winged Pegasos dropped his master

When he wanted to ascend the terraces of the sky.

When Bellerophon reached for Zeus’ assembly.

The bitterest end lies in wait

however sweet the injustice.”

ὅτι τερπνὸν ἐφάμερον διώκων

ἕκαλος ἔπειμι γῆρας ἔς τε τὸν μόρσιμον

αἰῶνα. θνᾴσκομεν γὰρ ὁμῶς ἅπαντες•

δαίμων δ’ ἄϊσος• τὰ μακρὰ δ’ εἴ τις

παπταίνει, βραχὺς ἐξικέσθαι χαλκόπεδον θεῶν

ἕδραν• ὅ τοι πτερόεις ἔρριψε Πάγασος

δεσπόταν ἐθέλοντ’ ἐς οὐρανοῦ σταθμούς

ἐλθεῖν μεθ’ ὁμάγυριν Βελλεροφόνταν

Ζηνός. τὸ δὲ πὰρ δίκαν

γλυκὺ πικροτάτα μένει τελευτά.

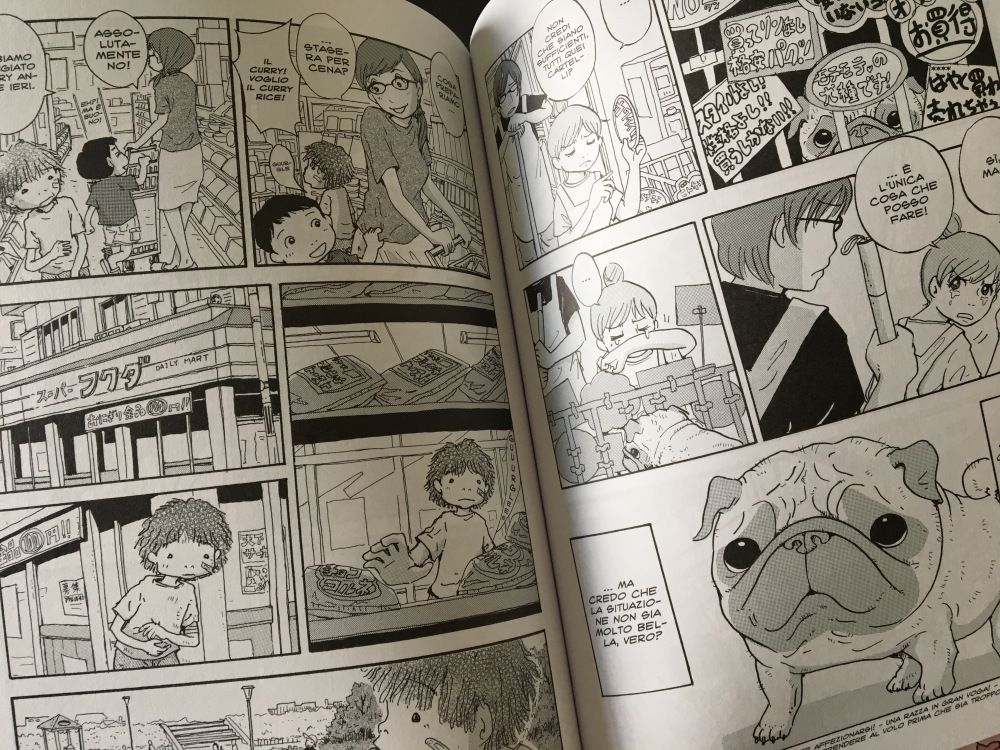

Red Figure by the Baltimore Painter, 4th Century BCE

Ah, don’t overreach! Yet, methinks Robert Browning might object (Andrea Del Sarto, Called “The Faultless Painter”):

“I, painting from myself and to myself, 90

Know what I do, am unmoved by men’s blame

Or their praise either. Somebody remarks

Morello’s outline there is wrongly traced,

His hue mistaken; what of that? or else,

Rightly traced and well ordered; what of that? 95

Speak as they please, what does the mountain care?

Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp,

Or what’s a heaven for? All is silver-gray

Placid and perfect with my art: the worse!

In one of my favorite modern pieces, the poet Jack Gilbert explores the theme of flying and falling in “Failing And Flying” (from 2005’s wonderful Refusing Heaven) where he begins and ends with a meditation on Icarus. The sentiments seem apt (the text comes from poetryfoundation.org):

Everyone forgets that Icarus also flew. It’s the same when love comes to an end, or the marriage fails and people say they knew it was a mistake, that everybody said it would never work. That she was old enough to know better. But anything worth doing is worth doing badly. Like being there by that summer ocean on the other side of the island while love was fading out of her, the stars burning so extravagantly those nights that anyone could tell you they would never last. Every morning she was asleep in my bed like a visitation, the gentleness in her like antelope standing in the dawn mist. Each afternoon I watched her coming back through the hot stony field after swimming, the sea light behind her and the huge sky on the other side of that. Listened to her while we ate lunch. How can they say the marriage failed? Like the people who came back from Provence (when it was Provence) and said it was pretty but the food was greasy. I believe Icarus was not failing as he fell, but just coming to the end of his triumph. The passage above from Pindar assumes some basic knowledge on the part of its audience, for instance: the connection between Bellerophon and Pegasos and how the former was in a position to fall from the latter. It is clear from the use of the figure as a negative example that the story had both broad currency and a typical understanding. A Scholiast in writing on Pindar’s 13th Olympian ode elaborates on the details of the fall (Schol. In Pindar Ol. 13.130c).

“For it is reported that when he planned to fly up on Pegasos and put himself in danger on high, he fell when Pegasos was bitten by a fly according to Zeus’ plan and he was crippled. So Homer says that he wandered crippled on the Alêion plain (Il. 6.201).

λέγεται γὰρ ὅτι ἀναπτῆναι βουληθεὶς τῷ Πηγάσῳ, κούφως παρακινδυνεύσας, κατὰ βούλησιν τοῦ Διὸς οἰστρωθέντος τοῦ Πηγάσου ἐκπίπτει καὶ χωλοῦται•

καὶ ἐπλανᾶτο κατὰ τὸ ᾿Αλήιον χωλός. καὶ ῞Ομηρός φησιν (Ζ 201).

The story of Bellerophon’s exile, told in Homer, is clarified or re-envisioned with the story of his downfall as articulated as a moral in Pindar. In Athenian Tragedy, Bellerophon became a popular figure (we have fragmentary plays by Sophocles and Euripides). Bellerophon’s eventual vengeance upon Sthenboia (an alternative for Anteia, Proitios’ wife) is the man story in Euripides’ play of that name that starts with a rumination on the trouble women cause for men:

Euripides, Stheneboia Fr. 661-662

“There is no man who is lucky in all things.

Either a man born noble has no livelihood

Or the baseborn ploughs fertile fields.

And many who boast of their wealth or birth

Are shamed by a foolish woman in their homes.”

Οὐκ ἔστιν ὅστις πάντ’ ἀνὴρ εὐδαιμονεῖ•

ἢ γὰρ πεφυκὼς ἐσθλὸς οὐκ ἔχει βίον,

ἢ δυσγενὴς ὢν πλουσίαν ἀροῖ πλάκα.

πολλοὺς δὲ πλούτῳ καὶ γένει γαυρουμένους

γυνὴ κατῄσχυν’ ἐν δόμοισι νηπία.

Just as Pindar uses Bellerophon as a vehicle to deliver a moralizing message, so too Euripides uses the hero to voice general concerns. In a second play on Bellerophon, Euripides returns to the moral content of Pindar’s complaint but, rather than simply portraying an instance of hubris, he offers a hero challenging the nature of divinity.

Here are two fragments from the lost Euripidean Bellerophon in which the eponymous hero denies that the gods exist. He does not seem to say that there are no gods at all, but his complaints are like those of Xenophanes who complains about the misbehavior of Homer’s gods.

Instead, Bellerophon’s complaints are based on the fact that since the world seems unjust and the gods are supposed to ensure justice, therefore they must not exist (either totally or in the form man makes them).

Euripides, fr.286.1-7 (Bellerophon)

“Is there anyone who thinks there are gods in heaven?

There are not. There are not, for any man who wishes

Not to be a fool and trust some ancient story.

Look at it yourselves, don’t make up your mind

Because of my words. I think that tyranny

Kills so many men and steals their possessions

And that men break their oaths by sacking cities.

But the men who do such things are more fortunate

Than those who live each die piously, at peace.

I know that small cities honor the gods,

Cities that obey stronger more impious men

Because they are overpowered by the strength of their arms.”

φησίν τις εἶναι δῆτ’ ἐν οὐρανῷ θεούς;

οὐκ εἰσίν, οὐκ εἴσ’, εἴ τις ἀνθρώπων θέλει

μὴ τῷ παλαιῷ μῶρος ὢν χρῆσθαι λόγῳ.

σκέψασθε δ’ αὐτοί, μὴ ἐπὶ τοῖς ἐμοῖς λόγοις

γνώμην ἔχοντες. φήμ’ ἐγὼ τυραννίδα

κτείνειν τε πλείστους κτημάτων τ’ ἀποστερεῖν

ὅρκους τε παραβαίνοντας ἐκπορθεῖν πόλεις•

καὶ ταῦτα δρῶντες μᾶλλόν εἰσ’ εὐδαίμονες

τῶν εὐσεβούντων ἡσυχῇ καθ’ ἡμέραν.

πόλεις τε μικρὰς οἶδα τιμώσας θεούς,

αἳ μειζόνων κλύουσι δυσσεβεστέρων

λόγχης ἀριθμῷ πλείονος κρατούμεναι.

Euripides, fr. 292.6 (Bellerophon)

“If the gods do a shameful thing, they are not gods.”

εἰ θεοί τι δρῶσιν αἰσχρόν, οὐκ εἰσὶν θεοί.

Share this: