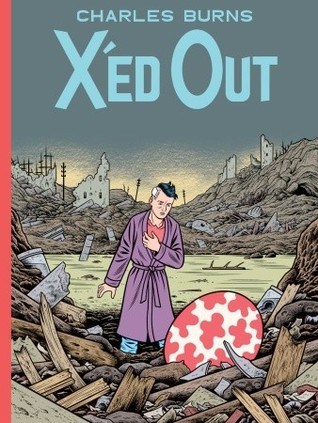

If you haven’t seen it, here’s a shout-out to a wonderful short film by the comics maker Charles Burns (probably most famous for Black Hole). It’s part of the anthology movie Fears of the Dark.

A sentient mantis-like insect has been secretly living with a socially awkward guy since childhood (puberty?). After the guy goes out on a rare date and hooks up with a woman, the critter joins itself to her by burrowing into her arm. Things go downhill from there in the couple’s incipient relationship.

Part of the film’s effectiveness comes from the fact that the disturbing “outer” story involving parasitical mantis creatures more than just parallels or comments on the “inner” story of an unhealthy obsessive relationship. I find the underlying reality of the story ambiguous enough that it easily works both ways. The insect material not only enhances the story of the toxic relationship, but the film takes its fantastical aspect seriously enough that sometimes the human relationship seems like the disturbing metaphor to what’s really happening with the mantis. (This ambiguity is partly possible because we only ever see the magical insect stuff when the guy is alone or with the girl.) Like the famous rabbit/duck image, the reality constantly reverses direction. The overall effect is that you can’t imagine one without the other.

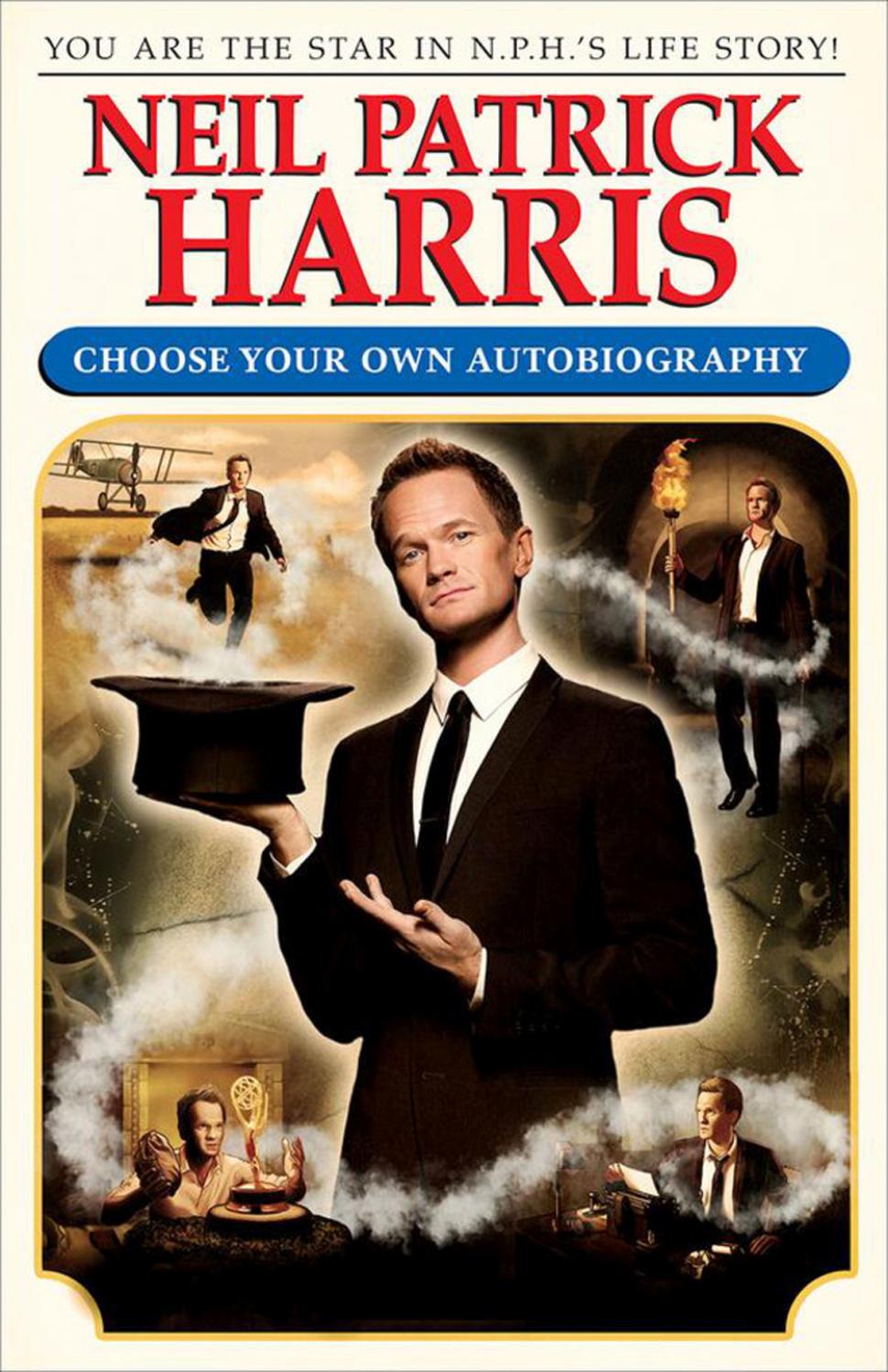

As my partner angrily pointed out, this intense little film can be contrasted with Burns’s three-part graphic novel X’ed Out. (Part 2 is called The Hive, and part 3 is called Sugar Skull.) I agree after reading it myself. The comic jumps between different timelines and prominently features a recurring segment in a strange fantastical landscape. The basic real-life story – mostly unfolded in the third volume – is pretty simple.

A pretentious self-involved fart named Doug has an affair with a woman named Sarah (they don’t otherwise have much chemistry). She gets accidentally pregnant. Her abusive boyfriend then finds Doug and punches him in the face. He runs away to his parents’ house. Sarah decides she wants the baby, tries to contact Doug, and he avoids her. Now it’s many years later and he feels bad about it, but Sarah understandably wants nothing to do with him.

I guess if Sarah’s kid wants to find out about his father, he’ll do so someday. And presumably if Doug actually wants forgiveness or to reconnect with Sarah, he’ll do more than just surprise visit her once out of the blue. I mean, this isn’t a tragic fate of missed opportunities, of archetypal conflicts between desires and responsibilities or anything like that. It’s just a guy who hurts himself and other people for no good reason and feels kind of bad about it.

The three volumes all look beautiful and are filled with vivid detail, and Burns does a great job circling around the future explanation to make the first two volumes intriguing and weird. But the big question is whether that explanation is worthy of the extended fantasy material featuring a princess, a comic book retrieval mission, pig-like creatures, lizards, giant eggs, and fetuses.

Throughout the first two volumes, Burns makes it clear that Doug actively avoids even thinking about What Actually Happened, the big source of trauma that splits his memory into fantasy. And as far as I can tell, the parallels between fantasy and reality seem largely superficial. The stuff that connects the fantasy with Doug’s imaginative life – like comics, absurdist performance art with a Tin Tin mask, and polaroid portraits – doesn’t do much to make him or his problems more fascinating. Nor do certain images like a bottled dead pig or a picture of Sarah holding a heart or him saying he’d rather have his picture taken with his mask on (see, because it’s like he’s always wearing a mask OK you get it). Finally, it doesn’t help that both he and Sarah treat their period of art-making like it was nothing but a meaningless phase, unless we’re supposed to think (without evidence) that he’s turning it all into a comic. I think that if you tore out the fantasy and made it into its own comic book, readers would say things like “this returns to many of the images and ideas we find in Burns’s earlier work!” but they wouldn’t see it as particularly augmenting or augmented by the real-world story of X’ed Out.

The Fear of the Dark short can be seen as a more successful counterexample. So is David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive, in which the story of a jealous woman who hires someone to kill her lover and ends up committing suicide is bracketed by an extended episodic fantasy. The fantasy sequence that takes up most of the movie seems worthy of the psychic trauma that it tries to reorganize. As my partner puts it, when you open up a distinction between fantasy and reality, the fantasy has to be sufficiently motivated by the reality. Children’s stories and coming of age tales often turn on this gap between fantasy and reality. Stories like Jim Henson’s The Labyrinth use their fantastical imaginings to try to work through the main character’s real-life problems. If enough of the two sides stick together, we’ll take seriously stuff like David Bowie’s twin role of antagonist and object of sexual desire. The fantasy and reality are already two different things, and the storyteller’s work lies in bringing them into some kind of meaningful relation.

Advertisements Share this: