Discussions about craft are important in any medium, but in writing they can be particularly insightful because the they are delivered by the medium in which they seek to explore. My favorites include Stephen King’s On Writing and John Gardner’s The Art of Fiction, and I recently added James Wood’s How Fiction Works to the list. (Henry James’s preface to his 1908 New York edition of Portrait of a Lady, which is at once exquisite (as is all James) and illuminating, also makes the list even though it is relatively short).

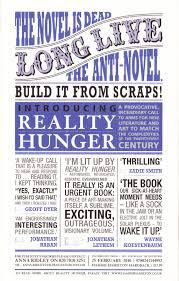

I was going to start this reflection by claiming that there is no better recipe for cognitive dissonance than reading the Wood book in the midst of revising a novel and then following it with David Shields’s Reality Hunger (a “manifesto” published seven years ago heralding the need for a new genre, a book that I finally decided to read in order to see the extent to which any of his predictions have come true–by and large, they haven’t), but I hesitated because I believe that exact phrasing was used by Michael Pollan in an excerpt about Peter Singer that I used to teach in my classes so often that I’ve memorized its phrasings (one of two reasons, the other being cost, that I no longer assign textbooks in my classes–if I’m going to be absorbing other writers’ words, I might as well exercise more choice; not that Pollan is bad, but that excerpt is nothing compared to the phrases I have memorized regarding rhetorical appeals and kinds of arguments, all of which were written by well-meaning educators who fall short in style).

So I’ll use it. Why not? If I hadn’t attributed it no one would have known the difference except perhaps for a slim number of Pollan fans who read him for his prose stylings rather than his ideas, and I have my doubts that there are any such fans in the first place. (I admit there may be one or two other teachers who have used that same textbook and have similarly memorized such passages, but I don’t expect they will mind a little playful near-plagiarism, especially since they do are not required to file an official report of any kind.)

So I’ll use it. Why not? If I hadn’t attributed it no one would have known the difference except perhaps for a slim number of Pollan fans who read him for his prose stylings rather than his ideas, and I have my doubts that there are any such fans in the first place. (I admit there may be one or two other teachers who have used that same textbook and have similarly memorized such passages, but I don’t expect they will mind a little playful near-plagiarism, especially since they do are not required to file an official report of any kind.)

Reading Shields’s book made me rethink the merits of fiction in today’s fractured landscape, and much of what he claims is true. Use it all, use everything, and let the line between what’s true and what’s made up, what’s yours and what’s someone else’s–let that blur completely. Erase it. Free yourself to include whatever you need for your story, and tell the truth but tell it slant and erect an edifice to your own point-of-view instead of creating made-up, stale characters who abide by restrictive dictates to seem true even though they’ve been confined to something unreal.

It’s a fine idea, but scratch it just slightly and it bleeds. We have a thirst for what’s real and what’s true, sure. We want to be close to the story, and there is less place for the novel, especially the Realist literary novel, the kinds that win the big Bookers, the Pulitzers, the National Book Awards, the Nobels. Americans rarely win the Nobel in fiction, which some see as a clear sign that our fiction no longer reflects the times or the culture.

Recently I had jury duty, and while many people were on their computers and phones as we all tried to stave off boredom, more than half of the people were reading, and of those more than half were reading novels. The novel had two centuries during which it moved from art to Modernist high art, from which it then became entirely deconstructed and left to piece itself back into its two dominant forms, at least in English–the realist novel and the post-modern hodge podge. It competes with increasingly ornate and complex televised worlds, and people can no longer find the time for everything we now have access to.

So Shields is right. The time of the novel is over, but so is the time of memoir. So, in some respects, is the time of writing. Where his book fails–and I’m probably not the first to write this since 2010 given how media has become even more convoluted–is in being a book and not a fleeting multimodal digital object that everyone can respond to and engage with. Why not publish it on a blog? Because sending it out as a book was safe and is still the way for a well-established writer to reach their audience. Because there’s still money there. Real bravery would have been taking it to the web, but where’s the infrastructure? Where are the readers? The real risk would have been posting it and the chance that no one would read its 200 plus pages. For all of its brevity, it is still indigestible for the internet.

And yet.

And yet there will always be readers. There will always be a segment of us who enjoy lengthy texts because we’re willing to follow along with a writer’s thoughts. There will always be those of us who crave story and want to be transported by words to other places, to spend time with other people, and yes, to explore and appreciate life-altering theses that are wrapped up in ornate packages of narrative and consciousness because we want to better understand ourselves. The realms of fiction are “time” and the “mind,” and both are mysteries we have yet to fully understand.

Advertisements Share this: