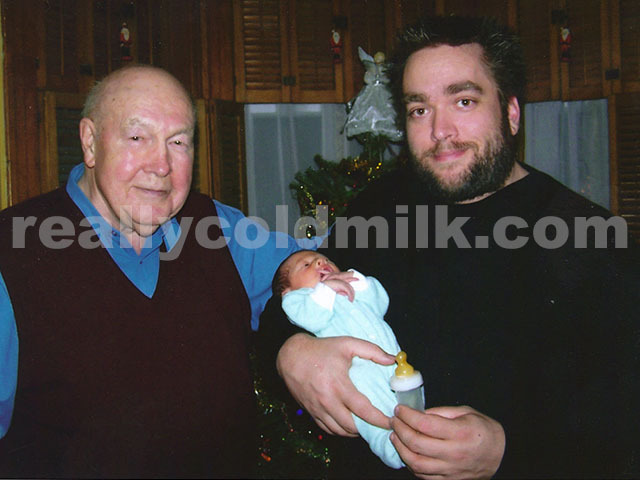

tl;dr: …I like some things more than others. Also, it’s a photo of my grandfather, my oldest son, and me. It’s one of my favourites.

.

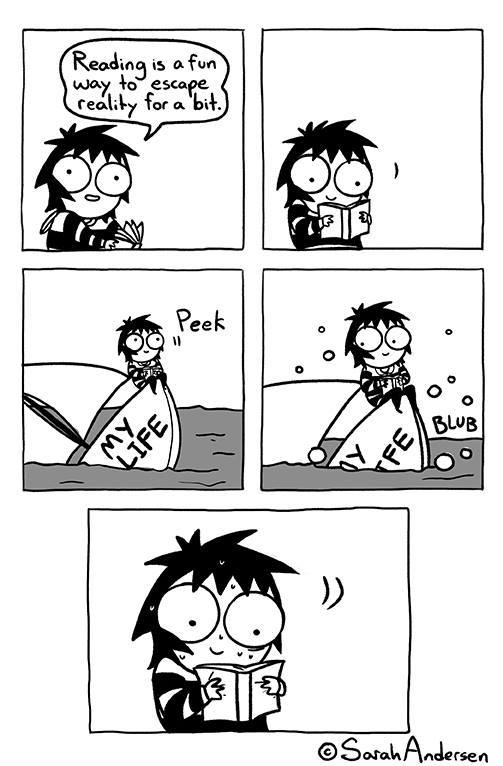

I’ve been reading a lot recently… or a lot more than I have been in the past year, anyway. It has been difficult, thanks to the medications I’m on to suppress my immune system (ie: prednisone). Very difficult, actually.

Being in the hospital for 4.5-months out of the past year didn’t help either (April 27 to July 31, and all of January, 2017). Mostly, while laying in bed 20-hours a day, my anxiety level was so high all I could manage was to watch TV and sleep.

So, basically, my brain was shut off for half a year. In January, while I was recovering from my kidney transplant, my cousin brought me two Hemingway novels — ‘The Sun Also Rises’, and ‘For Whom The Bell Tolls’. I used to read a book a week, so I was pleasantly surprised it only took me a few days to read ‘The Sun Also Rises’… which was excellent, but that was literally the first book I’ve read since early last spring (reading Dr. Seuss to Victor notwithstanding).

So, now that I’ve been home for a few weeks, and the lower dose of prednisone is making it possible for me to think again, I thought I’d dig around the boxes of books in the basement to find some reading material. And I managed to find some of my favourite books.

And these are them… since my brain is still fried, I’ve selected reviews from Goodreads.com to stand in for the brilliant analysis I would normally offer (except for ‘Ten Lost Years’, I wrote that one all by myself).

.

1. Ten Lost Years 1929-1939: Memories of Canadians Who Survived The Depression, by Barry Broadfoot (1973)

“‘Ten Lost Years’ is an historical compilation of hundreds of heart wrenching first-person stories of starvation, murder and astonishing stories of survival told by farmers, widows, waitresses, hoboes and desperate families willing to do almost anything just to live another day [during the Great Depression].

“Each single one of the hundreds of stories is simply overwhelming on their own, but one after the other they create an awe-inspiring testimony to the strength and absolute willpower these people had to have in order to survive what has to be the greatest series of natural disasters human beings have had to cope with, maybe only comparable to The Black Plague, HIV/AIDS and The Spanish Flu.”

—awesome words by Me.

2. Mockingbird, by Walter Tevis (1980)

…this is my favourite book.

“Mockingbird is a powerful novel of a future world where humans are dying. Those that survive spend their days in a narcotic bliss or choose a quick suicide rather than slow extinction. Humanity’s salvation rests with an android who has no desire to live, and a man and a woman who must discover love, hope, and dreams of a world reborn.”

–synopsis by Goodreads.com

“If Tevis’s ‘The Man Who Fell to Earth’ was (loosely, and maybe controversially) an SF allegory of Christ’s time on earth, Mockingbird is an allegory of the story of the Bible from Adam and Eve through the New Testament. Except that the snake in the garden was a [suicidal] robot who got rid of Adam so he could keep Eve for himself? Yeah. It’s complicated.”

—Julie, Goodreads.com

3. Occidentalism: The West In The Eyes Of Its Enemies, by Ian Buruma and Avishai Margalit (2004)

“…trace[s] the intellectual history of “the dehumanizing picture of the West painted by its enemies.” In the authors’ view, major elements of this picture, though not necessarily the whole, are shared by ISIS, Al Qaeda, Hezbollah, the Muslim Brotherhood, nineteenth-century Russian Slavophiles, Hitler’s Nazis, Mao’s revolutionaries, extreme Hindu nationalists, and the Japanese militarists who plunged their country into World War II. In many of its manifestations, they assert, Occidentalism gives rise to a death cult, rating “honor higher than morality” and glorifying death as the noblest response to the violation of great ideals.”

—Mal Warwick, Goodreads.com

4. Arizona Ames, by Zane Grey (1930)

…it’s like chick-lit for boys, with some horse-ridin’, gun-fightin’ and cattle-rustlin’ thrown it to keep it from getting too girly.

—Hawthorn, Goodreads.com

5. A Thousand Splendid Suns, by Khaled Hosseini (2007)

There were times, reading this, when I literally couldn’t breathe, and felt like the bottom had dropped out of my stomach. But this story is beautiful, and enlightening and hopeful even through all the gritty, heart-wrenching, almost physically painful emotional rawness of it.

— Becky, Goodreads.com

6. Sticks & Stones, George Bowering (1962 / 1989)

7. How It All Began: The Prison Novel, by Nikolai Bukharin (posthumous: 1998)

From the NY Times: “One of the more noteworthy of the many documents that have poured out of the opened archives of the former Soviet Union is this autobiography in the form of a novel by Nikolai Bukharin, generally regarded as the most prominent of the Bolshevik leaders killed in the Stalinist purges of 1937 and 1938. During his months in prison, Bukharin, who had fallen afoul of Stalin in 1929 and was stripped of his power then, wrote four books, including a philosophical work and “How It All Began,” a portrait of a sensitive young son of the lower middle class and his acquisition of a political conscience.

“The truth is that “How It All Began,” newly translated from the Russian by George Shriver, is more important for its historical than its literary value. That does not mean that it has no literary value. Bukharin, writing in his cell at night after all-day interrogations by the Stalinist police, produced a rich portrait of Russian life at the end of the 19th century. It is etched in nostalgia for youthful days in the countryside but also replete with terse descriptions of the tawdriness, the poverty, the brutishness of life under the czars.

“Bukharin’s book was published in Moscow in 1994, 56 years after his death. It is half essay, half novel, and had it been written by an unknown, it would certainly not figure very prominently as literature today. It is important for the glimpse it gives into the mind of a central figure of the Russian Revolution, the youngest of the circle around Lenin, who called Bukharin “the golden boy of the revolution.”

8. Zealot: The Life And Times of Jesus of Nazareth, by Reza Aslan (2013)

The author’s attempt here, unlike Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens, is not to ridicule the contradictions in the New Testament, but to rather present as historical a narrative as possible to describe the world of Jesus. And through that painstakingly detailed research concludes which parts of the New Testament seem plausible and which parts just cannot be.

—Mario Sundar, Goodreads.com

9. A Fair Country: Telling Truths About Canada, by John Ralston Saul (2008)

In this startlingly original vision of Canada, renowned thinker John Ralston Saul argues that Canada is a Métis nation, heavily influenced and shaped by Aboriginal ideas: Egalitarianism, a proper balance between individual and group, and a penchant for negotiation over violence are all Aboriginal values that Canada absorbed.

–synopsis by Goodreads.com

10. The Adventures Of Huckleberry Finn, by Mark Twain (1884)

Hemingway said American fiction begins and ends with Huck Finn, and he’s right. Twain’s most famous novel is a tour de force. He delves into issues such as racism, friendship, war, religion, and freedom with an uncanny combination of lightheartedness and gravitas.

—Nathan Eilers, Goodreads.com

…anyway. The video is my favourite from bands started by a friend.

“I don’t mind” by K-Man & The 45s, from their 2016 self-titled album.

.