Blade Runner, released in 1982, became a landmark in cinema blending the imagination of science fiction and the bleakness of classic noir elements. Directed by Ridley Scott, the film stunned the audiences in the cineplexes by taking what essentially is an art house vision of the future and expanding it into the mainstream expanse of the modern theater. Yet, the film always felt a tad off.

The narration felt out of place, the violence not as dangerous as the world surrounding it and the ending was something left to be desired. Fortunately, time had been kind to the film with a Director’s Cut filling some of the void in 1992 and an international cut that retained the danger of the brutality. In 2007, the film was given the treatment cinephiles felt it deserved with Scott back to supervise and recut what many consider his masterpiece. Blade Runner: The Final Cut solidifies that statement.

Based on the novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick, Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford), a former Blade Runner whose job was to kill (“retire”) bio-engineered androids known as Replicants. Though retired, Officer Gaff (Edward James Olmos) and Captain Harry Bryant (M. Emmett Walsh) inform Deckard of four Nexus 6 model replicants that have come to Earth illegally from an Off-World colony including Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer) and Pris (Darryl Hannah). Deckard heads off to the Tyrell Corporation for more insight on why the replicants might be on Earth, Deckard comes upon the Replicant named Rachael (Sean Young), a new experimental replicant who can pass easily for an ordinary human. With this new information at hand, Deckard returns to retire the replicants for good.

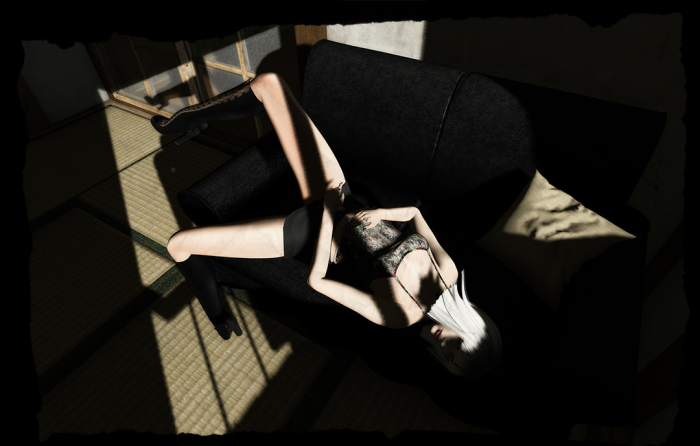

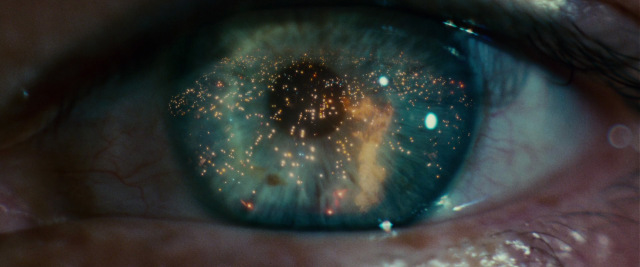

The Final Cut captures the essence of what Scott envisioned in the first go around. It’s intimate, dire, epic and hopeful. From the opening shot entering a Los Angeles rooted in fire and darkness, Scott shows that this story is going to be rooted within that heavy darkness. Brightness appears here and there, but in short bursts to add visual levity to the heaviness that surrounds. It’s remarkable in its production and scope with a combination of models, matte paintings and soundstages to make the year 2019 a grimy one. Among it, however, is a detective story firmly inspired by the noir genre complete with a femme fatale, a down-and-out detective and an antagonist after something they long for. While no Macguffin is clearly present, the desire to be human and be more than just what one currently feels omnipresent in the characters.

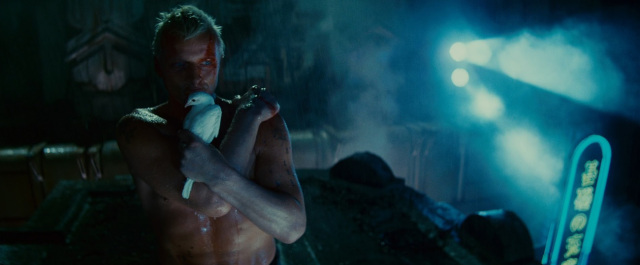

Huaer as Batty evokes this feeling in his performance standing out among the humans as someone with true emotion and understanding. Batty desires the sense to be a better model in the same vein as Rachael despite going through nefarious means to get to that point with the others. Batty is more than just an automaton, but rather as complex as the framework he is made with. Deckard evokes this trying to get back in the swing of things and the desire to escape his old Blade Running days with his romantic interactions with Rachael. He has a burden on his back to himself stuck in his hard drinking retirement looking for a form of purpose. Rachael, who is not completely aware of her replicant state, desires to know her purpose in life and why she is desireable to both parties. The performances from all three add significance and weight to their respective characters in the desire to be their ideal version of humanity. The story is made stronger as well going from a simple noir story to a intricate one about the err of humanity and technology.

Vangelius’ score is the sound of the future, even at this point in time. Elements of old jazz and cliche noir stylings are blended with synthesizers, strings and ambience. It’s meticulous in its design going from the darkest of tones to the most hopeful of sounds seamlessly as the film progresses and goes on. Not once does it feels hokey or oft-putting, but rather adds. Even the love theme, complete with sensual saxophone, does not feel out of place in its structure. Scott’s direction and work of cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth gives the desired result of the neo-noir setting with the starkness of black, the beautiful terror and wonder of night and the marginal greatness of daylight when it appears. Certain shots, including the shot of the Geisha advert and the sun setting, can be art pieces in their own right. The pacing is methodical, but never boring with visual effects that are stunning in their practicality from built models of flying cars, rear projections of the backgrounds and violence that feels real and brutal.

Blade Runner: The Final Cut is a masterpiece of cinema taking what came before it in the realms of mystery, action and science fiction to blend it into gorgeous mixture. It excites and provokes the mind by perfecting a vision that more than just androids can dream.

Advertisements Share this: