Almost fifteen years ago, I attended a public lecture by Frank Deford, who applied his winding wit and signature vocal timbre to the athletic matters of the day: drugs, collegiate sports, and, of course, soccer culture, his great nemesis. At that time, in the fall of 2004, I probably was as far as I have been from the person who would later start a sports-focused website, but I knew well Deford’s voice through his NPR essays, which he began delivering in 1980, and didn’t want to miss the opportunity to meet one of the greats in person. Knowing him only from his radio work, Deford’s striking physical presence, upon seeing him for the first time, immediately both impressed and made exact sense; the vocal and corporeal likely never have been more perfectly combined.

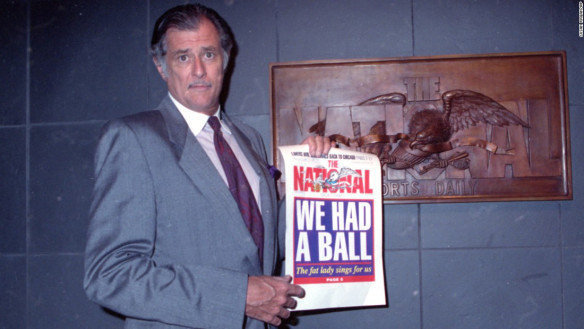

His authority in the field was obvious, but it wasn’t until later that I would discover the source of that authority: his print work, including a trove of articles for Sports Illustrated, where he started after graduating from Princeton in 1962, and, arguably even more influentially, his role as editor-in-chief of The National Sports Daily, the forefather to the more recently revered Grantland. Deford also wrote for Vanity Fair and Newsweek, produced novels and screenplays, and contributed to CNN and HBO’s Real Sports.

News broke yesterday that Deford, seventy-eight, died on Sunday. Steve Rushin, SI‘s best current columnist, shared this remembrance:

When I lucked into a fact-checker job with Sports Illustrated in 1988, and prepared to move to Manhattan, my Minnesota dentist said to me during a valedictory teeth-cleaning: “So, you wanna be the next Frank Deford?”

The truth was, I just wanted to see Frank Deford, standing at the copy machine in the Time & Life Building, in a smoking jacket, regaling passersby with anecdotes. Such was the image I’d conjured of him as a reader of his stories, whose titles I could recite from memory: “The Rabbit Hunter,” “The Boxer and The Blonde,” “Raised By Women to Conquer Men.” He had more hits, over more decades, than Sinatra.

Of course, I never did see Deford in the SI office. If he ever descended Olympus and dropped by, I wasn’t in. So when he left the magazine to start The National Sports Daily, I walked from Sixth Avenue to Fifth Avenue to interview over there, almost exclusively in the hope that I’d meet him. But alas, he wasn’t in those unfurnished offices either, and over the ensuing years I began to take comfort in the old adage that you should never meet your heroes.

And then one day a mutual friend summoned me to Westport, Conn., to have lunch with the great man himself. In person, Frank was even nicer than he was smart, and even smarter than he was tall. And he was very, very tall. It turns out you can and should meet your heroes.

“You have a wonderful canvas on which to paint,” he said to me of column writing, and ever-after I began to think of him as the world’s greatest muralist. (The ugly word longform, which ought to be reserved for tax returns, didn’t yet exist.)

Frank once wrote that when people hear you’re a sportswriter, they assume you’re far more interested in the first half of that word—sports—than in the second half: writer. And while Frank was deeply interested in both—and was also, rather unfairly, an excellent broadcaster—he was above all a writer, a writer without equal, a writer you could only aspire to see, not to be.

A few weeks ago, a colleague at SI forwarded a lovely e-mail from Frank about something I had written. In it, Frank mentioned that Cole Porter as a Yale undergraduate wrote “Bulldog,” which remains the Elis’ fight song to this day. That was the Frank I grew up reading. He knew something about everything, from Cole Porter to Cole Hamels.

Years ago, he sent me another kind message, this one hand-written on a note card in his favorite color: purple. I have kept it on my desk so long in the sunlight that the words have faded away, leaving only FRANK DEFORD in the upper left corner. I cherish it all the more now, a blank canvas, awaiting paint.

Three weeks before his passing, NPR aired Deford’s final commentary, itself crafted as a farewell. The transcript is available here, but you’ll cheat yourself if you don’t listen to the audio, which you can find at the same linked page.

Advertisements Share this: