Although computer and console role-playing games share a lot of common ground with their tabletop predecessors, over time the two media have diverged significantly.

Western role-playing games arguably remain the truest to tabletop role-playing, which remains very freeform, flexible and sometimes even completely free of violent conflict. Titles such as Bethesda’s The Elder Scrolls series allow the experience of living in a virtual world, exploring as you see fit and seeing what happens as you interact with it in various ways.

Japanese (and Japanese-inspired) role-playing games, meanwhile, are typically (though not exclusively) handled almost as “interactive storybooks” punctuated by regular, predictable and abstract battle sequences. This isn’t a criticism, mind; as any JRPG fan will tell you, this approach allows the games to focus on strong storytelling and characterisation at the expense of allowing you to steal every spoon in someone’s house.

This article was originally published on Games Are Evil in 2012 as part of the site’s regular Swords and Zippers column on JRPGs. It has been republished here due to Games Are Evil no longer existing in its original form.

One area in which tabletop RPGs and JRPGs differ is in the concept of “encounters.” In a traditional tabletop game, the term “encounter” is used to describe a single episode in a larger quest — this may or may not involve conflict, or may simply be a special challenge which the party of heroes has to overcome. In a JRPG, meanwhile, the term “encounter” is often used to refer to the many, many battles in which the party will engage on the way to whatever their objective is at that point: the term “encounter rate” is typically used to describe, quite simply, how many steps you take on average before you get into a fight.

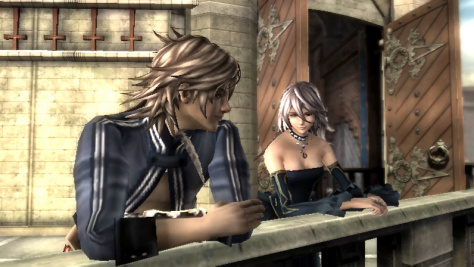

The Last Story, from Final Fantasy creator Hironobu Sakaguchi’s Mistwalker studio, flips this concept on its head and takes an approach to “encounters” much more akin to what you’d come across in a typical session of, say, Dungeons and Dragons. While The Last Story’s encounters are still largely combat-focused, there’s a level of depth and interaction to them that sets this unusual game very much apart from the JRPG genre you may know all too well by now.

To understand what I’m describing, it’s necessary to be familiar with The Last Story’s combat system. Unlike many JRPGs, combat in The Last Story takes place in real-time, with players taking control of a single character: protagonist Zael. Up to five additional characters may join Zael in combat, but the player only ever has control over Our Hero. As the game progresses, however, additional game mechanics open up and allow for a variety of different tactics to be used, ranging from Zael’s “Gathering” ability — which effectively draws aggro onto him and away from his compatriots — to the ability to “dispel” allies’ magic circles in order to provide a range of different effects.

Notably, though, The Last Story’s encounters don’t all hinge on piling atop a monster and whittling down its health bit by bit while ensuring the mages don’t get hit: no “tank and spank” or “holy trinity” of character classes here. No, in many cases, a bit of clever strategizing before the battle begins — something that the game encourages you to do by providing you with a top-down tactical view before you jump into a dangerous situation — can put the player’s party in a significantly superior position, up to and including, in some cases, seeing the battle concluding before it has really begun.

Zael’s ability to hide behind environmental obstacles and fire his crossbow as well as perform devastating “stealth attacks” allows him to manipulate the flow of battle and enemy positions before everyone else gets involved. A first-person “focus” mode also allows the player to give various orders to their companions — for example, to instruct the mages to bring a rocky outcrop crashing down on the heads of the hapless enemies underneath.

The whole experience of combat encounters in The Last Story gives the game a very cinematic, exciting feel quite unlike any other JRPG I’ve ever played — and, hell, quite unlike any other RPG in general, regardless of its country of origin or inspiration.

All this has the side-effect of meaning that every battle in the game makes sense in context of the narrative rather than simply providing you with repetitive groups of enemies to get in your way as you approach a destination, and it also means that everything you do feels like it “counts.”

It also means that the game keeps level-grinding to an absolute minimum — though those players who are absolutely determined to min-max their characters can do so at special dedicated “summoning circles,” where you can spawn enemies and fight to your heart’s content. It’s a significant change from the typical conventions of the JRPG genre, and a very welcome one.

This increased focus on unique, exciting encounters and a significantly-reduced need for level-grinding has a few knock-on effects on the overall game structure, too. Unlike Monolithsoft’s 100+ hour epic Xenoblade Chronicles – a game which likewise shook up the conventions of what the term “JRPG” actually means, and a title often mentioned in the same breath as The Last Story due to its part in the Operation Rainfall campaign — you can be done and dusted with The Last Story within 25 to 30 hours.

And far from this being a negative thing, it aptly demonstrates that just because a game is an RPG, it doesn’t need to be bloated with a ton of “filler” content to artificially inflate its playtime. No; The Last Story’s plot remains tight, focused and fast-paced throughout the entire game, with only a few occasions of completely optional “downtime” providing anything off the beaten track for players to accomplish.

Chances are, however, that because you’ve had such a rollercoaster ride with these characters by the time you reach one of these quieter periods, you’ll relish the chance to explore the game’s extraordinarily well-realized single city setting to seek out its hidden quests and treasures, and further immerse yourself in the world.

The Last Story, then, is a noteworthy title not just for being one of the last great games for the Wii, but also for challenging the very conventions of a whole genre. “JRPG” doesn’t have to follow its stereotype of “spiky-haired, sullen teenager saves the world while being attacked by monsters every five steps and occasionally wandering off to do something completely unrelated.”

Sometimes it can tell a much shorter, tighter tale and, taking its cues from the tabletop definition of “encounters,” provide some exciting, memorable and unique experiences for the player rather than simply asking them to click the “Attack” button over and over again.

This article was originally published on Games Are Evil in 2012 as part of the site’s regular Swords and Zippers column on JRPGs. It has been republished here due to Games Are Evil no longer existing in its original form.

If you enjoyed this article and want to see more like it, please consider showing your social support with likes, shares and comments, or financial support via my Patreon. Thank you!

Advertisements Share this: