Management: This essay is meant to be less of a review and more of analysis of the show being examined. It contains plot spoilers for the Girls’ Last Tour anime.

The world has ended. Earth hasn’t been annihilated out of existence. Human society though, the world of our anthro-centric leanings, has certainly passed its twilight into the dark. The cities are gutted wrecks of their former heights, their exposed chests jagged ribs of industrial dilapidation and war carnage. The remnants of decaying civilization echoes the biblical hubris of Babel, a tower built tall to touch God’s fingertips, to be abandoned before it could be completed, its builders dispersed to the four corners. This time though, the builders have been reduced to near nothingness. Humanity is on verge of extinction, and its wreckage, instead of worrying…

…the girls of Girls’ Last Tour get wasted on moonshine and start doing an intoxicated jig.

I swear to drunk moe blobs that I’m going somewhere serious with this. But first, some tunes:

And now a history lesson.

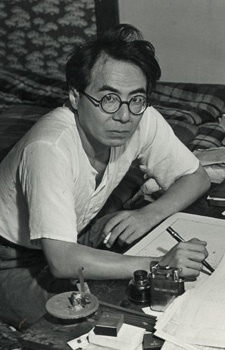

Fragmented concrete fingers and black carbon smears were what most cities in Japan were like immediately after WWII. There was a lot of reflection and re-evaluation done by Japanese thinkers about where things went wrong. Not too long ago, people walked and talked about the glory of empire and the honor of the nation. Now, the most important activity on people’s minds and appetites were more survival and less suffering. In the early years of the post-war, defined as much by sleezy debauchery as by daily struggle, folk such as Ango Sakaguchi, Osamu Dazai, and Sakunosuke Oda rose to literary and cultural prominence. These thinkers, the so-called decadents, suggested that the devastation of the country came about because of this mass obsession about something outside of themselves instead of their own individual persons.

Glory isn’t real, and the nation is an imaginary concept. In believing in and fighting for these artifices, despite and because of their considerable industry, the Japanese people have brought themselves into destitute material ruin. But rather than bemoan their homeland’s terrible conditions, these decadent writers saw in its current circumstances a great opportunity. This opportunity parallels the same sort of transitory period often mentioned in existentialist thought, the moment when illusions of higher purpose are shattered and people are challenged with thoughts about the meaninglessness of life. Un-occluded by the delusions of grandeur that enforced a regime of state-run and self-imposed austerity, disillusioned individuals could now return to their authentic selves and embrace their humanity.

What does this “authenticity” and “humanity” entail? Their meanings are individualistic and hedonistic for the decadents. Rather than work their existences for the glory of the nation or some other overarching goal, as many had done previously and uncritically, the Japanese were exhorted by the decadents to enjoy life for themselves, on their own terms. A person should not abstain from having a drink, making love with multiple people, or creating art because society deems it unproductive, improper, or immoral. A couple should or should not raise kids because the state needs more workers and soldiers. A pair should or should not marry each other because the culture says it would bring dishonor to their families. People should act how they want to, and they have no obligation to behave otherwise.

Our drunk moe blobs from Girls’ Last Tour also find themselves in a post-war world. Chiito and Yuuri roam where their whims take them, their movements limited only by where they could physically get to and where there is food and fuel. They react to and enjoy life as they encounter it:

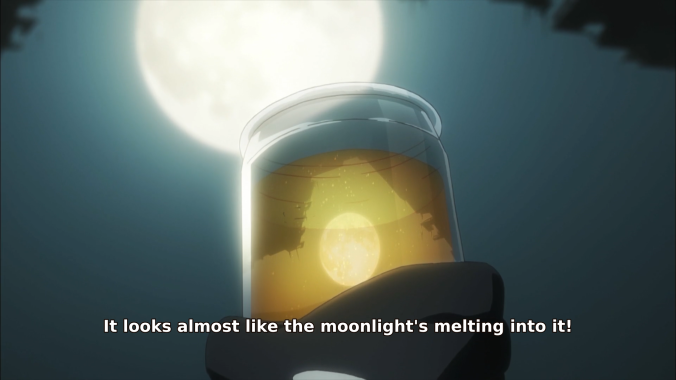

(1) Soaking down in a makeshift hot tub; (2) eating a fish that they discovered while doing laundry; (3) making music with empty cans and raindrops; (4) baking biscuits with old ovens and leftover ingredients; (5) marveling at the monoliths left behind by previous civilizations; (6) drinking alcohol they randomly foraged from a deserted building; (7) dancing in the moonlight.

All these activities, by themselves, aren’t much out of the ordinary in a time and place in human history where creature comforts are abundant and readily accessible to most, but the inhabitants of Girls’ Last Tour and the immediate post-WWII Japan aren’t privileged with these luxuries:

(1) the hot tub is made with a section of a gouged-out water pipe; (2) they’ve never seen a fish before; (3) they’re using rather primitive music makers; (4) the biscuits are just baked dough with sugar sprinkled on top; (5) the people who constructed the monoliths are all dead; (6) holy shit this fizzy yellow stuff makes feels really good when you drink it what the —-; (7) they’re celebrating despite the depravity around them.

In slice of life where cute girls manage to do cute things with what they have on hand and encounter despite living in the post-apocalypse, we get to appreciate the simple pleasures that the audience enjoys in the mundane and takes for granted. For the decadent thinkers of post-WWII Japan, doing the things that we want to do for our own sakes, no matter how simplistic or vacuous-seeming, is the height of decadence. That’s a good thing.

You’d also think in all post-apocalyptic fictions, you’d see more people, or at least some people, attempting to rebuild human civilization or repopulate the world with humans due of some big goal of saving humanity from extinction or some grand aim of making humanity great again. But no. In Girls’ Last Tour, a man named Kanezawa is focused on mapping out the city ruins. In the show, a woman named Ishii is busy building planes she can fly around in. The universe has already established that there are very few human beings still alive in the world. The two of them both seem youthful enough to settle down and start a family if they ever encounter one other (or encounter someone fertile enough from the opposite sex). But far from concerning themselves with the destiny of the human collective — as people may be wont to believe is a universal duty everyone needs to fulfill during such trying human-depleted times — they’re doing instead what they individually want to do. The version of humanity that these effectively decadent adherents prize is one that’s individualistic and hedonistic.

In Girls’ Last Tour, the human race has already passed its twilight and drifted into the dark, with very few human beings left alive to do accomplish much of anything deserving a monolith… except for what they can do for themselves. Even in these tired times, human beings like Chii and Yuu are still able to celebrate, dance, and sing in the moonlight.

“Dancing in the Moonlight” is a take-it-easy, happy-go-lucky, feel-good pop song that people today might associate with decadence. However, it was recorded in the US during a time when global annihilation was a looming specter for people everywhere. The song could be interpreted as a call for audiences to re-prioritize what they really value: inviting them to enjoy life instead of fretting over it. The world as the Japanese once knew it terminated with a war and atomic bombs. The world as the ruined civilization that Chii and Yuu travel through probably met a similar end. They ended, most likely, because people fretted over some higher purpose. Additionally, what right do the older generations have to force the younger ones to clean up their mess and carry on their lifestyles? Perhaps if humanity were only a little more decadent back then and abandoned their grand external ambitions for simplistic and vacuous-seeming pleasures — if only human beings were truer to ourselves, according to the decadents, and less obsessed with what they were not — maybe their worlds wouldn’t have ended in the first place.

But as it stands, in the moment that matters, Chii and Yuu are together. They danced. They’re drunk. They are happy.

Advertisements Share this: