by Patrick Ehlers & Drew Baumgartner

This article contains SPOILERS. If you haven’t read the issue yet, proceed at your own risk!

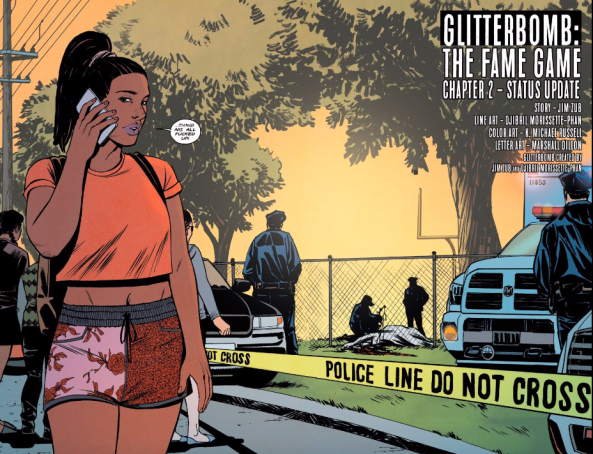

Patrick: What are we doing here? I mean, here, reading (or in my case, writing) a piece critical of a work of art? The art itself, issue two of Glitterbomb The Fame Game, is an exploration of emotional voyeurism, and is openly critical of the people profiting off the vulnerability of others. The risk associated with saying anything about this issue is always going to pale in comparison to the risk the creators take in actually expressing the story therein. Writer Jim Zub and artists Djibril Morissette-Phan and K. Michael Russell lay their own fears of fame out on the page in naked, sometimes groaningly obvious, ways. I can point this out and say “look how obvious this is”, but this is always going to be a weaker product than the story that actually says something.

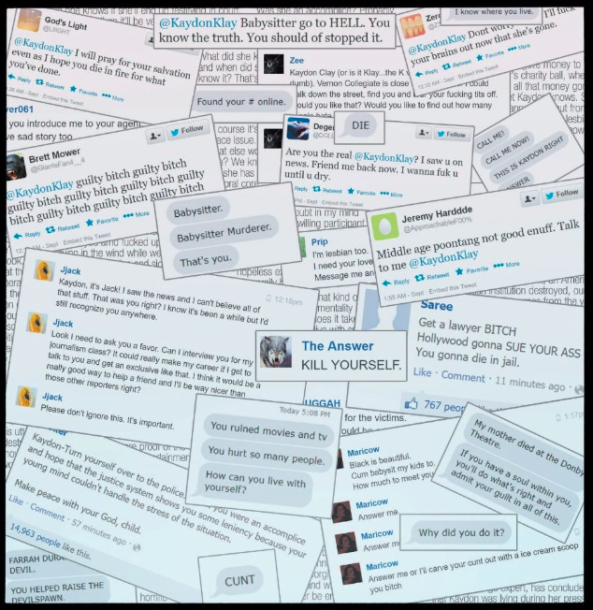

The panel that lays out these risks is a collage of internet hate that Kaydon gets in response to being on Newswire. Twitter and Reddit and even our own comment sections can be shitty places for reasonable discourse — I’ve been told to “get fucked to death” for not praising a Godzilla comic highly enough — and Zub et. al let their worst impressions of the internet run amok on the page.

There are the classics within the deluge: both the ubiquitous “KILL YOURSELF” and the pithy, one-word message “CUNT” make all-caps appearances. But so do the messages that start off sounding like uncomfortably aggressive compliments and quickly morph into rape and death threats. This is the public’s reaction to Kaydon sincerely expressing emotions on television. Chelsie, the Newswire reporter who put the whole thing together is probably also going to be the target of some similar vitriol, but as she’s not the one offering her own emotions, she’s not nearly as concerned. It’s a damn chilling moment when her producer puts forth the concern “we’re going to get complaints,” only to be met with a cold “what else is new?”.

Where Zub, Morissette-Phan and Russell differentiate their message is in how they actually present the emotional moments of this issue, and by extension, the same manipulative moment of Chelsie’s segment. Russell’s colors soften and Morissette-Phan’s design of Marty morphs into an intensely adorable version of itself. It begs the question: who’s creating this saccharine moment? The TV crew or the comic creators?

There is, of course, a layer of artifice no matter how we answer that question. The emotion the reader responds to belongs to one party (Marty and Kaydon) but is packaged by another. Both the agent and the reporter are necessarily more guarded throughout this process than Kaydon is.

Zub and Morissette-Phan telegraph the danger of Kaydon’s vulnerability early in this issue. There’s a poster on her bedroom wall on page one for the Darren Aronofsky flick Black Swan. The movie follows a young ballerina’s meltdown as she eventually gives all of herself to the lead role in Swan Lake. Spoilers for Black Swan: the exercise kills her. Nina, as portrayed by Natalie Portman, gives one hell of a moving performance, but she pays the ultimate price for it.

Drew, I know I’ve driven us to this “what’s the point of criticism?” conclusion before, and I never totally manage to convince myself that there’s no value in what we do. We are frequently vulnerable, offering readings that say a hell of a lot about what we fear. I guess the vulnerability I’m showing right now is my own insecurity about the value of my craft. In fact, maybe it’s damn myopic of me to even turn my reading into a commentary on how I engage with art. But the issue invites that kind of self-exploration, and is extremely honest about it to boot. Perhaps to a fault, but, hey, who am I to judge?

Drew: I think the difficulty is that we live in an age where “criticism” has expanded to include things that have nothing to do with critical discourse. There was a time when critics had read enough Barthes to draw a hard line between the critique of a work of art and a personal attack of the artist — you know, in addition to being decent human beings and being accountable to their publications. But the the internet has allowed amateurs with no accountability, familiar with The Death of the Author only as the subject of a threatening tweet, and emboldened by anonymity to call themselves “critics,” often feigning disbelief when artists push back on this stuff, suggesting that they are too sensitive to take “criticism.” Obviously, we’re most cued into this phenomenon in the comics world (where the confusion of serious analysis and ad hominem attacks cheapens what we do here), so it’s hard not to see a little bit of Zub’s own twitter feed (and Tumblr Q&A) reflected in that flood of hate Kaydon receives.

The difference, of course, is that Kaydon is a sixteen-year-old, whose entire sense of self-worth relies on the opinions of others (even anonymous trolls). Where Zub doesn’t seem daunted by jerks being jerks, Kaydon reads those messages and comments just after being kicked out of her house — these are the only connections she has to humanity at that point. It makes her easy prey for the hate monster at the heart of Glitterbomb.

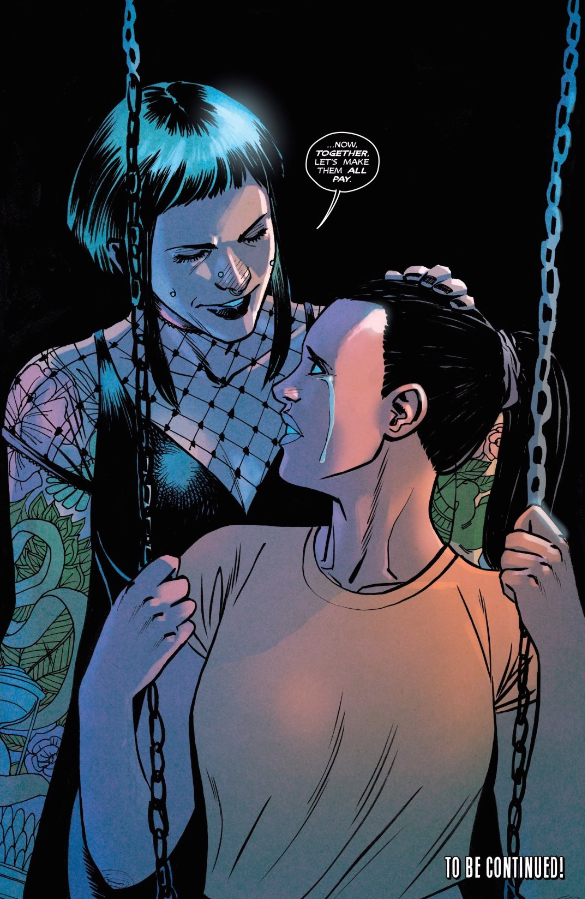

The thought of getting revenge on all of these people — some kind of internet karma — reminds me a great deal of the Black Mirror episode “Hated in the Nation,” where the villain seems to be stoking the internet’s worst tendencies, only to then punish users for their inhumanity. But as much as Kaydon may want to see these people suffer, this monster clearly isn’t offering catharsis. It may seem like the monster has Kaydon’s best interests at heat, but all it really wants is to keep her misery all to itself.

In that way, I think the commentary this issue makes on the internet’s weird way of dehumanizing people is a lot more complicated than it might seem. We might be on the monster’s side for holding Chelsea accountable for her actions — though we’ll hopefully agree that head-eating takes it a bit too far — but the monster’s motives to luxuriate in Kaydon’s misery forces us to question our own. Are our we virtuous for virtue’s sake, or do we get some kind of perverse joy out of feeling like saviors (thus requiring that there be people to save)? Are the monsters better or worse than the people they’re killing, or are they all just part of the same cycle?

Lest we get too philosophical, let’s talk about that head-eating for a second:

First off, I love that Zub and Morissette-Phan have come up with a totally different design for this monster — it suggests a larger, weirder mythology behind whatever is going on here. But the thing I love most about this sequence is that, in it’s eagerness to eat Chelsea’s head, the monster also eats most of the headrest. That little detail sells the violence and viciousness of the attack more than the arcs of blood or dangling spine. This monster isn’t even delicate enough to eat only heads.

But, of course, the fact that this thing consumes heads is important. As I suggested earlier, it’s a hate monster, fueled by internet trolls and misery, this thing will literally eat your head. Ascribing morals to it or to the anonymous posters on the internet might be hopelessly misguided — all we (or Kayden) can really do is either give in to its pressure or fight against it. This issue leaves her at the precipice of that decision, but I’m not sure Kayden has the emotional maturity to make the moral choice here. I’ll stop short of making any hard predictions, but it seems to me that The Fame Game might be more about explicating the cycle of fame than it is about breaking it.

For a complete list of what we’re reading, head on over to our Pull List page. Whenever possible, buy your comics from your local mom and pop comic bookstore. If you want to rock digital copies, head on over to Comixology and download issues there. There’s no need to pirate, right?

Advertisements Share this: