By Van Smith

Published as a “Postmark: Baltimore” column in New York Press, 1998

Back in August 1996, when I moved into the house I recently purchased, my next-door neighbors appeared to be a problem. A bullethole still marred a windowframe of their rented house, left there after a Sunday afternoon shootout on the street a few months earlier. They kept seven chows in the basement; you could hear the inbred curs barking in the dark, day and night. About a dozen people used the house as a temporary crash pad on a rotating basis – younger guys, mostly, with shiny Acuras and eye-fucking attitudes. The landlord lived in New York City and apparently was waiting for the bank to foreclose on the property so he wouldn’t have to be responsible for the shady scene going down on his property.

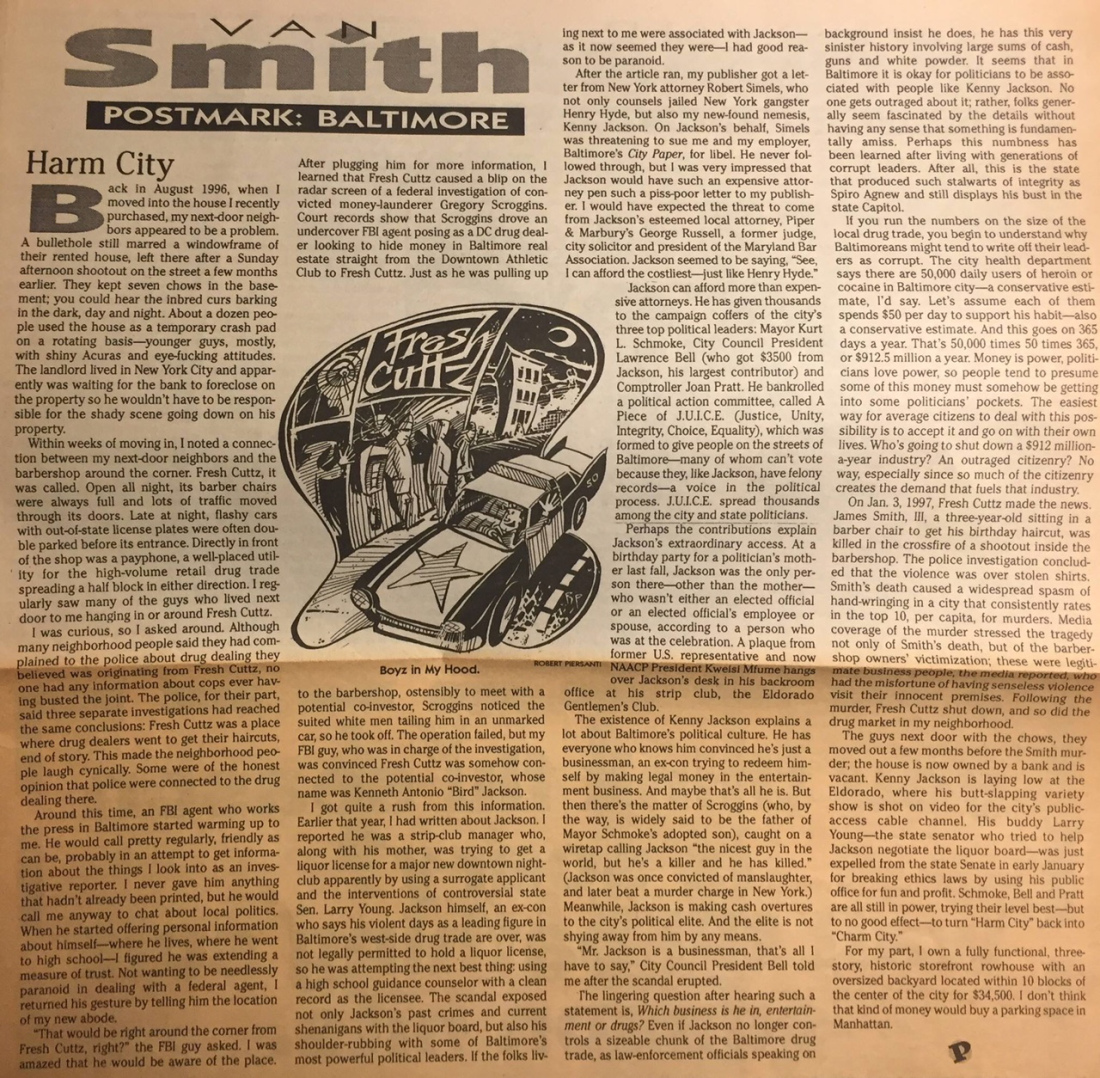

Within weeks of moving in, I noted a connection between my next-door neighbors and the barbershop around the corner. Fresh Cuttz, it was called. Open all night, its barber chairs were always full and lots of traffic moved through its doors. Late at night, flashy cars with out-of-state license plates were often double-parked before its entrance. Directly in front of the shop was a payphone, a well-placed utility for the high-volume retail drug trade spreading a half block in either direction. I regularly saw many of the guys who lived next door to me hanging in or around Fresh Cuttz.

I was curious, so I asked around. Although many neighborhood people said they had complained to the police about drug dealing they believed was originating from Fresh Cuttz, no one had any information about cops ever having busted the joint. The police, for their part, said three separate investigations had reached the same conclusions: Fresh Cuttz was a place where drug dealers went to get their haircuts, end of story. This made the neighborhood people laugh cynically. Some were of the honest opinion that police were connected to the drug dealing there.

Around this time, an FBI agent who works the press in Baltimore started warming up to me. He would call regularly, friendly as can be, probably in an attempt to get information about the things I look into as an investigative reporter. I never gave him anything that hadn’t already been printed, but he would call me anyway to chat about local politics. When he started offering personal information about himself – where he lives, where he went to high school – I figured he was extending a measure of trust. Not wanting to be needlessly paranoid in dealing with a federal agent, I returned this gesture by telling him the location of my new abode.

“That would be right around the corner from Fresh Cuttz, right?” the FBI guy asked. I was amazed that he would be aware of the place. After plugging him for more information, I learned that Fresh Cuttz caused a blip on the radar screen of a federal investigation of convicted money-launderer Gregory Scroggins. Court records show that Scroggins drove an undercover FBI agent posing a DC drug dealer looking to hide money in Baltimore real estate straight from the Downtown Athletic Club to Fresh Cuttz. Just as he was pulling up to the barbershop, ostensibly to meet with a potential co-investor, Scroggins noticed the suited white men tailing him in an unmarked car, so he took off. The operation failed, but my FBI guy, who was in charge of the investigation, was convinced Fresh Cuttz was somehow connected to the potential co-investor, who name was Kenneth Antonio “Bird” Jackson.

I got quite a rush from this information. Earlier that year, I had written about Jackson. I reported that he was a strip-club manager who, along with his mother, was trying to get a liquor license for a major new downtown nightclub apparently by using a surrogate applicant and the interventions of controversial state Sen. Larry Young. Jackson himself, an ex-con who says his violent days as a leading figure in Baltimore’s west-side drug trade are over, was not legally permitted to hold a liquor license, so he was attempting the next best thing: using a high school guidance counselor with a clean record as the licensee. The scandal exposed not only Jackson’s past crimes and current shenanigans with the liquor board, but also his shoulder-rubbing with some of Baltimore’s most powerful political leaders. If the folks living next to me were associated with Jackson – as it now seemed they were – I had good reason to be paranoid.

After the article ran, my publisher got a letter from New York attorney Robert Simels, who not only counsels jailed New York gangster Henry Hyde, but also my new-found nemesis, Kenny Jackson. On Jackson’s behalf, Simels was threatening to sue me and my employer, Baltimore’s City Paper, for libel. He never followed through, but I was very impressed that Jackson would have such an expensive attorney pen such a piss-poor letter to my publisher. I would have expected the threat to come from Jackson’s esteemed local attorney, Piper & Marbury’s George Russell, a former judge, city solicitor and president of the Maryland Bar Association. Jackson seemed to be saying, “See, I can afford the costliest – just like Henry Hyde.”

Jackson can afford more than expensive attorneys. He has given thousands to the campaign coffers of the city’s three top political leaders: Mayor Kurt L. Schmoke, City Council President Lawrence Bell (who got $3500 from Jackson, his largest contributor) and Comptroller Joan Pratt. He bankrolled a political action committee, called A Piece of J.U.I.C.E. (Justice, Unity, Integrity, Choice, Equality), which was formed to give people on the streets of Baltimore – many of whom can’t vote because they, like Jackson, have felony convictions – a voice in the political process. J.U.I.C.E. spends thousands among the city and state politicians.

Perhaps the contributions explain Jackson’s extraordinary access. At a birthday party for a politician’s mother last fall, Jackson was the only person there – other than the mother – who wasn’t either an elected official or an elected official’s employee or spouse, according to a person who was at the celebration. A plaque from former U.S. representative and now NAACP President Kweisi Mfume hangs over Jackson’s desk in his backroom office at his strip club, the Eldorado Gentlemen’s Club.

The existence of Kenny Jackson explains a lot about Baltimore’s political culture. He has everyone who knows him convinced that he’s just a businessman, an ex-con trying to redeem himself by making legal money in the entertainment business. And maybe that’s all he is. But then there’s the matter of Scroggins (who, by the way, is widely said to be the father of Mayor Schmoke’s adopted son), caught on a wiretap calling Jackson “the nicest guy in the world, but he’s a killer and he has killed.” (Jackson was once convicted of manslaughter, and later beat a murder charge in New York.) Meanwhile, Jackson is making cash overtures to the city’s political elite. And the elite is not shying away from him by any means.

“Mr. Jackson is a businessman, that’s all I have to say,” City Council President Bell told me after the scandal erupted.

The lingering question after hearing such a statement is, Which business is he in, entertainment or drugs? Even if Jackson no longer controls a sizeable chunk of the Baltimore drug trade, as law-enforcement officials speaking background insist he does, he has this very sinister history involving large sums of cash, guns and white powder. It seems that in Baltimore it is okay for politicians to be associated with people like Kenny Jackson. No one gets outraged about it; rather, folks generally seem fascinated by the details without having any sense that something is fundamentally amiss. Perhaps this numbness has been learned after living with generations of corrupt leaders. After all, this is the state that produced such stalwarts of integrity as Spiro Agnew and still displays his bust in the state Capitol.

If you run the numbers on the size of the local drug trade, you begin to understand why Baltimoreans might tend to write off their leaders as corrupt. The city health department says there are 50,000 daily users of heroin or cocaine in Baltimore city – a conservative estimate, I’d say. Let’s assume each of them spends $50 per day to support his habit – also a conservative estimate. And this goes on 365 days a year. That’s 50,000 times 50 times 365, or $912.5 million a year. Money is power, politicians love power, so people tend to presume some of this money must somehow be getting into some politicians’ pockets. The easiest way for average citizens to deal with this possibility is to accept it and go on with their lives. Who’s going to shut down a $912 million-a-year industry? An outraged citizenry? No way, especially since so much of the citizenry creates the demand that fuels that industry.

On Jan. 3, 1997, Fresh Cuttz made the news. James Smith, III, a three-year-old sitting in a barber chair to get his birthday haircut, was killed in the crossfire of a shootout inside the barbershop. The police investigation concluded that the violence was over stolen shirts. Smith’s death caused a widespread spasm of hand-wringing in a city that consistently rates in the top 10, per capita, for murders. Media coverage of the murder stressed the tragedy not only of Smith’s death, but of the barbershop owner’s victimization; these were legitimate businesspeople, the media reported, who had the misfortune of having senseless violence visit their innocent premises. Following the murder, Fresh Cuttz shut down, and so did the drug market in my neighborhood.

The guys next door with the chows, they moved out a few months before the Smith murder; the house is now owned by a bank and is vacant. Kenny Jackson is laying low at the Eldorado, where his butt-slapping variety show is shot on video for the city’s public-access cable channel. His buddy Larry Young – the state senator who tried to help Jackson negotiate the liquor board – was just expelled from the state Senate in early January for breaking ethics laws by using his public office for fun and profit. Schmoke, Bell and Pratt are all still in power, trying their level best – but to no good effect – to turn “Harm City” back into “Charm City.”

For my part, I own a fully functional, three-story, historic storefront row house with an oversized backyard located within 10 blocks of the city of the city for $34,500. I don’t think that kind of money would buy a parking space in Manhattan.

Share this:

- Share