Viv Albertine, best known as the guitarist in the 70s ‘girl punk’ band. The Slits, and as the author of her unflinching memoir Clothes Clothes Clothes Music Music Music Boys Boys Boys (2014), she’s also a sculptor, a filmmaker, a keep-fit guru and actress. But whatever the role, Viv has never lost her inner punk; provoking, rebelling and non-confroming.

‘I’m not a legend, but I do feel like a survivor’Failures are the interesting parts of life – not always the happy moments.

Viv was born in Sydney in 1954, but moved to North London at the age of 4. Her father was French, “odd and difficult”. One day in 1965, he left the family home, never to return. Growing up on the feral side, her Mum trying to make ends meet, Viv dropped out of Art School and fell in with the angry music crowd of 70s London, we call the punks.

On childhood role models…

“Girls were nothing in the ’70s. If you hadn’t been born into a decent family and had a decent education as a girl you were fuck all. There were no role models. On a class level it was just awful – nothing was expected of you. It’s a wonder more girls weren’t delinquent in the ’70s but we didn’t even have that! We didn’t have that drive, that energy to be bad. It was such a small box we were in. To break out of that, it’s no wonder guys didn’t like us.”

“There weren’t many role models for a girl in the early 70s so for a long time it was just my mum. Luckily she was strong, intelligent and opinionated. After that there were girlfriends of the Beatles and the Stones, they had a very high profile – Marianne Faithfull, Anita Pallenberg especially. Then I copied boys; boys I knew, boys I didn’t know. They were doing the interesting stuff, having all the fun. When John Lennon got together with Yoko Ono, that was a game changer. At last a woman who had ideas – an artist, a radical. Me and my friends adored her.”

“I wasn’t a punk because it was trendy; I was a punk because that’s how I felt. And part of that was being honest and authentic and taking your vulnerabilities and making the most of them. Until I met Malcolm McLaren, Vivienne Westwood, Johnny Rotten, I was kind of embarrassed that I’d come from a poor family, I wasn’t very well educated, I couldn’t play guitar, I had no musical knowledge. All those things I felt were terrible setbacks for me and made me uncool, whereas when I met them, they were proud of the fact that they were coming into something unschooled and could bring a sort of passion and naiveness and a fresh eye to it. So they taught me that whatever you are, and whoever you are, shouldn’t ever limit your confidence or your dreams.”

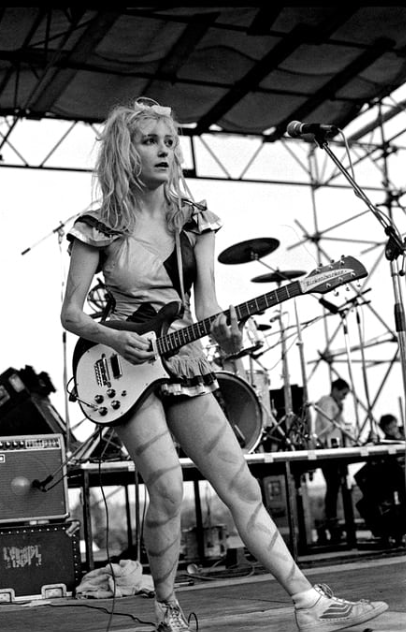

On dressing as a punk:

“People didn’t know whether to fuck us or kill us, because we looked like we’d come out of a porn magazine.”… “But something wasn’t quite right, with the bovver boots and the black makeup and the hair and the gobbing. We put them off kilter. We looked like aliens to them, so a guy seeing us in the street and being pissed off by us, they didn’t think they would have to treat us like girls.”… “Whenever I came back to Highgate, my mum used to meet me at the station with a kitchen knife in her pocket to protect me,”

“It made me realise that the streets are a bit safer now. Plus there were the IRA bombs going off then. There were the skinheads, the Teds. Men were much less emotionally educated than they are now. It was a very different world for a young woman, people were constantly hitting on you, and you were so objectified. But there was also violence. The minute we started dressing like we did, they had the attitude that if we dressed like freaks, they’d treat us like freaks. We didn’t even have that tiny bit of respect that a man had for a woman – even that was gone by the time The Slits walked down the road. We weren’t even treated like humans. We were nothing.”

The Slits, “Cut” album cover (1979)

The Slits, “Cut” album cover (1979)

On being in The Slits (with singer Ari Up, bassist Tessa Pollitt and drummer Palmolive):

“We were like a gang, and it gave us an enormous strength and confidence. We were so fired up to protect each other. I realise now that a lot of the boys were desperate to be rock stars. But being girls and having no role models, we really did come at it fresh: we filtered all the influences and made them our own.”

“We went everywhere together, we were like sisters in a gang. We were just absolutely knitted together and for all the pain of that – the squabbles, the competition between us as girls – at the same time, we were as one. After losing that identity overnight, I had to rebuild Viv Albertine as a person. That purpose, to make people understand about The Slits, had been my mission every day and that had gone. It’s not like it was a mission that I was broken-hearted to let go of because I didn’t believe in it any more anyway, but it was a painful separation, like a terrible break-up between lovers.”

On becoming an aerobics instructor:

“It was so exciting, girls moving their bodies. Before the early 80s, the only times girls moved their bodies was doing hockey or whatever at school, which everyone tried to get out of. This was really liberating: a sweaty room, packed with women, throwing their bodies around, sweating, looking dirty, no makeup.”

In her 30s, Viv marries and desperate for a child, moves to Hastings. After a miscarriage she spent years in fertility clinics until finally she gives birth to a much-longed for daughter. Three months later she was battling cervical cancer.

On IVF:

“By the time I’d done it for five or six years, I could spot a woman who was on IVF just from the sad, haunted look on her face. It’s the hardest thing I’ve been through – and I count cancer in that. It was soul-destroying. I couldn’t even work anymore. I went from being someone who was going to go to LA and make feature films, to someone who could barely leave the house. I just had to have a baby. It was madness, it was biological, it was a raging female fire.”

For 12 years she played Hasting Housewife, rarely talking of her punk past, hiding her artistic talent. A call from an American artist, Vincent Gallo, woke her up.

On divorce:

“I could still be sitting there by the sea, squabbling and bickering with a husband like many hundreds and thousands of people are. But I could not do it. You’ve got one life. It felt like an insult to nature to stay somewhere because you are scared. I understand if you’re afraid of being lonely why people stick it out. But I think everyone should be moving around when something is over.”

With Liam Gillik in Exhibition (2014)

With Liam Gillik in Exhibition (2014)

On starting her creative career again:

“I couldn’t sing or play a note. I hadn’t touched a guitar for 25 years, so I had to sit down, in my late forties, and learn again. But I was absolutely driven like never before. I was like a volcano exploding. Whether it was being pent up within the marriage, becoming well after the illness, or just a release from all the failures, the IVF, I don’t know.”

‘So I just plonked away for about six weeks or so and then one day as I played, I just sort of lost it and my hands started going mental. From somewhere the old style of Viv playing came, the weird, slightly atonal, slightly oriental thing that I do, and I wrote a song. Then it was like an avalanche, the songs just came pouring out. I became like a teenage boy, who had to be in his room playing every day. Nothing else mattered. It’s quite strange for a woman of a certain age to feel like this and I realised I hadn’t known what was going on in myself until it all came flying out from the guitar. I hadn’t realised how fucked up I was.’

“How does anyone make it through marriage and children and remain a whole person?”

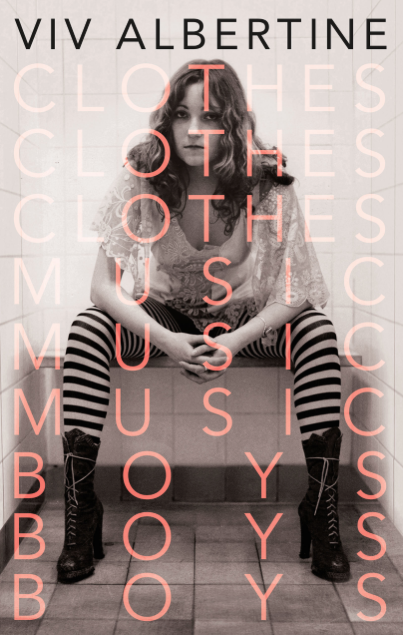

On writing her autobiography: “Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys”( “a punk self-help book”):

“I wrote the book to show all the hard work, failure, embarrassment, humiliation and lack of confidence that go into making up a woman’s life. The more blows you have in life the better because it means you’re challenging yourself”

“I want them to see how often you have to fail to be anything in life. I think young men and boys are taught to fail. It’s nothing to them; they do sport, they fall over, they shout: ‘I’m all right,’ and carry on. But with girls they’re so appallingly embarrassed to fail, it’s like it’s considered unfeminine.”

“So I sat down, and the first thing I thought was, “I’m not going to write this book wanting to be liked.” And all the way through the book I had to keep stopping myself from just slightly changing a sentence so that I came out a bit better, or just setting the scene so it wasn’t so boring. It was very hard as a woman to write not wanting to be liked, because we are appeasers and we like to please and we’re sort of brought up that way, and I had to keep throwing it out the window.”

On reaction to the book:

“It’s interesting that the book has really resonated. I don’t see it as a music book, it’s just the journey of a woman and the context is music. What’s really resonated is the honesty. I felt like nothing for 15, 20 years and now people say, “Oh Viv, you’re a legend,” and I thought, “Well, that’s funny because I’ve just been pushing my broom around my kitchen for the last 15 years feeling like shit, so how come I’m a legend?”

I think something I wanted to say, in a way, was, “You don’t have to throw away the ideology.” I tried to find a way that I can be older and still live by those punk maxims and I tried to show that in the style of writing too, in the punchiness of the chapters and in the way I’ve lived my life and still live it uncompromisingly, and how when I did compromise, I died. When I compromised, I faded away.

“I’ve exposed myself terribly and I don’t know what the consequences are going to be. Will I ever meet another guy now that I’ve written it? How’s it going to affect my daughter? Have I gone too far? I always go too far.”

With her daughter

With her daughter

On love:

” My dad died and I wrote “I don’t believe in love” the day I found out. We’d had a very difficult and fairly estranged relationship, so it wasn’t like I grieved him dying – I’d grieved a very long time ago. But the possibility that I’d ever have that nice dad who loved me and who I loved had gone. I started ruminating on love. Did he love me? Then I started thinking, has anyone ever really loved me? Have I really ever loved anyone? Is it actually just a made-up construct? I was in an emotional state that day and I just thought, fuck it, I’m not going to believe in this shit any more, I’m just going to believe in what I can see and what I can touch.”

“I’m still… I’m still really, really reassessing love. I don’t know if it’s ‘cos I’m a girl, if it’s because I’ve been raised on these bloody books and these fairy stories. I’ve got a 10-year-old daughter who’s being brought up on a lot of that rubbish as well. I just don’t want to be duped. I’m probably the most romantic idiot you’ll ever come across, and all my life I’ve wanted and hoped and believed in the big love and the soulmate and… I’ve lived with that concept since I was about nine-years-old, and believed in it since I discovered The Beatles. I’ve listened to the words of every song I’ve ever heard believing in it. If I’m going to let that go – and I am kind of letting that concept go – it’s terrible for me. It’s like my religion gone. But at the same time, comes the birth of something else. I don’t what that will be yet, whether it’s a more practical or a more honest way of living. Maybe out of the… I don’t know, the dregs…

“When you experience the death of a parent, whether you’re close to them or not, you reassess your life, because you see an arc that’s part of you. I saw my father’s arc of life and it had a profound effect. And that’s the gift they leave you, if you choose to take it.”

On being by herself:

‘I’m like a reluctant artist. I could hibernate for winter quite happily. I once went to bed for three months! When I’m burnt out, I take to my bed. I think there’s great value in daydreaming, away from social media or racing to see this band or that band. Just looking at a patch of sky…’

Viv hasn’t stopped writing though, a new memoir – “part brave reinvention of the memoir form; part feminist manifesto; part domestic noir; part love-letter to her mother; part autobiographical diary,” To Throw Away Unopened will be published by Faber on April 5 2018.

Further Reading:

https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/why-feminism-needs-punk-viv-albertine-slits-autobiography

https://www.loudandquiet.com/interview/viv-albertine-on-a-life-of-nonconformity-her-new-book/

Advertisements Share this: