Sarah Sundin concludes her series today on WWII and the role of the pharmacist. Wasn’t the information amazing? You can find Part I and Part II by following the links.

Welcome back, Sarah!

While researching the military medical system for my World War II novels, I read about physicians and nurses, dentists and veterinarians. But where were the pharmacists? In the civilian world, the physician prescribes medication, the pharmacist purchases, compounds, and dispenses, and the patient or nurse administers. I discovered the wartime military system differed. As a pharmacist I was baffled and intrigued.

While researching the military medical system for my World War II novels, I read about physicians and nurses, dentists and veterinarians. But where were the pharmacists? In the civilian world, the physician prescribes medication, the pharmacist purchases, compounds, and dispenses, and the patient or nurse administers. I discovered the wartime military system differed. As a pharmacist I was baffled and intrigued.

On February 14th, I discussed the role of the pharmacist in the 1940s. On February 16th, I described the local drug store and how its role changed during the war, and today I’ll review the rather shocking role—or lack thereof—of pharmacy and pharmacists in the US military.

Drug Distribution in the Military

In the US Army and Navy, outpatient prescriptions were filled at base or unit dispensaries, while inpatient orders were filled at hospital pharmacies. Both dispensaries and pharmacies were staffed by enlisted personnel—pharmacy technicians in the Army and pharmacist’s mates in the Navy—under the control of physicians. In 1936, the pre-war Army had forty graduate pharmacists serving as enlisted technicians.

Pharmacy technicians did not need any previous health care background or education. They went through a three-month program based on practical training rather than scientific understanding.

Medical Administrative Corps

For decades, pharmacy organizations had lobbied for a Pharmacy Corps with commissioned pharmacists. Indeed, most nations had similar corps. However, the US Army Medical Department was run by physicians. They thought of pharmacists in a condescending manner as businessmen rather than professionals, and they saw the drug distribution system as adequate.

The Medical Administrative Corps was formed in 1920 as a compromise. The MAC was responsible for administrative duties within the Medical Department, including medication procurement and distribution. In 1936, the MAC was permitted to commission sixteen pharmacists, with future appointments in the MAC restricted to graduate pharmacists.

The number of officers in the MAC increased during the war. In 1943 six hundred graduate pharmacists served as MAC officers—but none of them served as pharmacists.

Options for Pharmacists

Since most draft-age pharmacists had four-year bachelor’s degrees, they were eligible to serve as officers. While physicians, nurses, dentists, and veterinarians were commissioned as officers and placed in appropriate positions, no such guarantee was available for pharmacists.

Upon enlistment, pharmacists could apply for the Army Officer Candidate School, but upon graduation, they could be assigned anywhere. Pharmacists served as infantry officers, artillery officers, and in many other divisions. Even if they happened to be assigned to the MAC, as noted above, they did not practice their profession.

If a pharmacist wanted to compound and dispense medication, his only option was to serve as an enlisted technician, with pay and privileges far below that of an officer.

Fight for a Pharmacy Corps

The American Pharmaceutical Association (APhA) renewed the legislative battle for a commissioned Pharmacy Corps. While the Surgeon General’s office argued that “Army pharmacy was simpler than civilian practice. The department’s three-month pharmacy technician course was sufficient preparation. There was little compounding. Since medications were furnished in tablet form, ‘any intelligent boy can read the label’” (1).

These arguments did not sit well with pharmacists—or with the general public. Dr. Evert Kendig of the APhA argued that “Army pharmacy technicians were given responsibility beyond that legally permissible in civilian life even as the Army misused its professional pharmacists” (1). Several incidents were reported of prescriptions improperly filled by technicians and of blatant physician prescribing errors that would have been caught by a pharmacist. Public opinion tipped the scale, and on July 12, 1943, President Roosevelt signed legislation authorizing the formation of the Pharmacy Corps.

Pharmacy Corps

The Pharmacy Corps was authorized to commission seventy-two pharmacists. However, the military moved slowly. In January 1944, after receiving 900 applications and conducting two-day written examinations, physical examinations, and interviews, twelve officers were commissioned. By January 1945, the Pharmacy Corps had only commissioned eighteen pharmacists. The other officers’ slots were filled by former MAC officers.

The drug distribution system did not change by the end of the war, but the formation of the Pharmacy Corps laid the groundwork for post-war reforms.

Resources:

********************************************************************************************

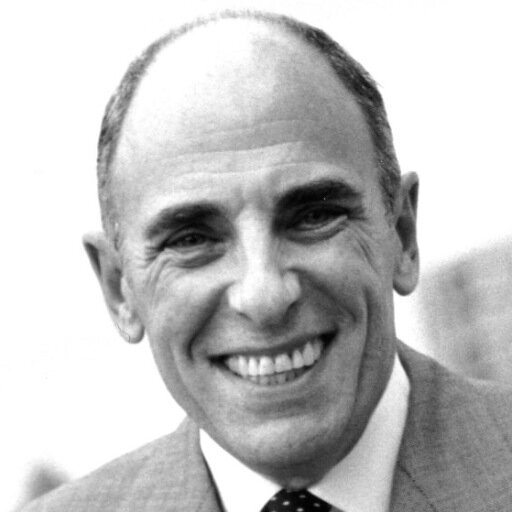

Sarah Sundin is the author of the Waves of Freedom series (Through Waters Deep, 2015, Anchor in the Storm, 2016, and When Tides Turn, March 2017), the Wings of the Nightingale series, and the Wings of Glory series, all from Revell. In addition she has a novella in Where Treetops Glisten (WaterBrook).

Sarah Sundin is the author of the Waves of Freedom series (Through Waters Deep, 2015, Anchor in the Storm, 2016, and When Tides Turn, March 2017), the Wings of the Nightingale series, and the Wings of Glory series, all from Revell. In addition she has a novella in Where Treetops Glisten (WaterBrook).

Her novel Through Waters Deep was a 2016 Carol Award Finalist, won the 2016 INSPY Award, and was named to Booklist’s “101 Best Romance Novels of the Last 10 Years.” Her novella “I’ll Be Home for Christmas” in Where Treetops Glisten was a finalist for the 2015 Carol Award. In 2014, On Distant Shores was a double finalist for the Golden Scroll Awards from both AWSA and the Christian Authors Network. In 2011, Sarah received the Writer of the Year Award at the Mount Hermon Christian Writers Conference.

A mother of three, Sarah lives in northern California, works on-call as a hospital pharmacist, and teaches Sunday school and women’s Bible studies. She enjoys speaking to community, church, and writers’ groups, and has been well received.

Share this: