N. Gray, MD

I have witnessed many code status discussions — good, bad, and ugly. Here is a smattering of the “not-so-pretty” code conversation patterns. Keep reading to the end for a suggestion on a better approach…

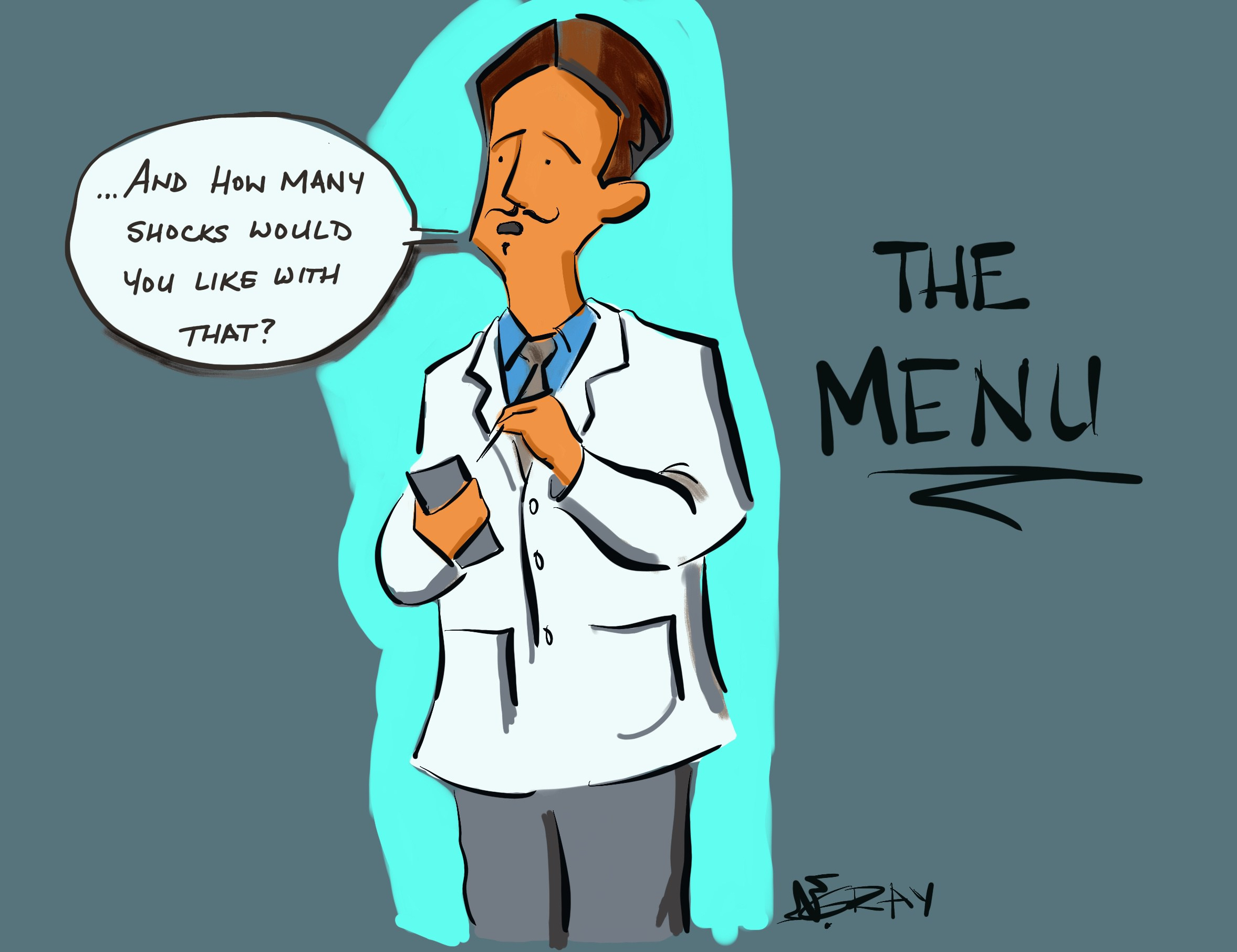

The Menu: This approach leaves patients to pick from an overwhelming array of interventions (pressors, shocks, tubes), some of which may be appropriate and some of which may not.

The Transcendent: This method presumes an understanding of a patient’s beliefs regarding something that may be deeply personal or metaphysical. It may sometimes be appropriate to reference deeper conceptions of dying, but only when patients have already shared their own views on death and what lies (or does not lie) beyond.

The Horrors: This approach uses scare tactics and horror stories about CPR to try to talk people into avoiding resuscitation. This may work in the short term, but feels emotionally manipulative or coercive. Often providers are describing their own fears about what CPR will feel like for them, rather than what the patient will experience.

The Numbers: This strategy involves bombarding patients with statistics, which are unlikely to be heard in the midst of a terrifying and emotionally charged decision.

The All-or-None: This approach involves offering patients a binary choice which implies that if they don’t choose the route of “everything,” then we will do nothing for them. Even patients choosing to avoid resuscitation attempts in the event of a cardiopulmonary arrest can have many helpful interventions to promote survival and comfort prior to and during the event.

These conversations are often difficult… after all, it’s life and death. If talking about resuscitation seems easy to you, there’s a chance you’ve forgotten how profound these decisions are for patients.

Here is my Code Status mnemonic, synthesized from the teaching and observation of many experienced and wise clinicians:

Context: What’s the setting of this conversation?After making sure it’s an appropriate time and place to talk, start with asking what someone knows about their medical condition. What have they been told? What have they heard? If there’s a large gap between your impression of their condition and their impression of how they’re doing, the rest of the conversation won’t make much sense, and it might be better to spend your time exploring what’s going on rather than trying to push code status decisions. Medical providers want to START with code status, but for patients it’s one of the last in a long line of steps toward digesting illness and mortality.

“What has your lung doctor told you about the progress of your emphysema?”

Concerns: Why do we need to talk about this right now?What is the reason for the conversation at this moment? Has something changed? Are you worried something WILL change? Rather than simply talking about a “heart stopping” or “lungs not working” it is OK in situations of advanced illness to be specific about the concerns that someone may DIE. (That is what cardiopulmonary arrest IS when it comes from advanced organ failure.) If a patient is otherwise healthy, and you’re just asking because it is required documentation, it’s also OK to say that.

(Chronic or Life-threatening Illness:) “Your oxygen levels have become dangerously low, and I am concerned that if things get worse, you could reach the point of dying from your lung cancer. Be READY to respond to emotion at this step, and STOP and allow space for grief and statements of support.

(Routine, Healthy): “Anytime you are in a medical setting, it is important to make sure that we understand your wishes in the instance of a life-threatening illness. Do you have any specific preferences about efforts at resuscitation if you were to experience a sudden life-threatening change in your health.”

Counsel: What is our medical recommendation based on your medical condition and preferences?After exploring the patient’s thoughts on dying and medical interventions at the end of life, provide a recommendation based on their preferences and condition. Use plain language and avoid jargon. Simplify statistical information into straightforward background for your recommendation. Provide a clear recommendation, remembering that even despite your best efforts to approach this conversation thoughtfully, patients and providers may disagree about the best way forward.

“I’m worried that, with the severity of your lung disease, CPR would be unlikely to help you recover. I would recommend that when your condition worsens to the point of dying, we should do everything possible to relieve your symptoms and support you, but we should not attempt CPR or artificial breathing.”

For further reading, see:

Charles F. von Gunten in Journal of Clinical Oncology2001;19:5, 1576-1581. Palliative Care Networks of Wisconsin’s Fast Fact #23AMA Virtual Mentor. September 2006, Volume 8, Number 9: 559-563.

Share this: