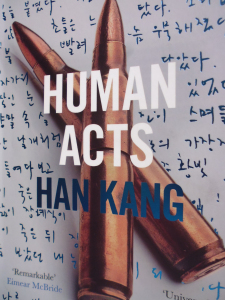

This novel is an account of the 1980 Gwangju Uprising in South Korea and the massacre  and repression which followed. Told from different points of view, the accounts are pieced together like a mosaic and tell us of those who died and those who survived- and the price they paid. The novel starts in the gymnasium where the small and slight middle schooler Dong-Ho has come to look for his friends Jeong- Dae and his sister Jeong- Mi. The gymnasium is the place where the bodies are brought from the hospital and laid out in coffins, some covered, some open, for families to identify. The bodies are swollen, already putrefying, many disfigured and maimed from blows and slashes.The stench is overwhelming. I was reminded of Nina Jäckle’s book der lange Atem where bodies are bloated and distended, hard to identify. There it’s the Tsunami which has caused such damage, whereas here it is humankind which has maimed, shot, crushed and tortured these mostly very young people in a brutal response by the state to their demands for freedom and democracy.

and repression which followed. Told from different points of view, the accounts are pieced together like a mosaic and tell us of those who died and those who survived- and the price they paid. The novel starts in the gymnasium where the small and slight middle schooler Dong-Ho has come to look for his friends Jeong- Dae and his sister Jeong- Mi. The gymnasium is the place where the bodies are brought from the hospital and laid out in coffins, some covered, some open, for families to identify. The bodies are swollen, already putrefying, many disfigured and maimed from blows and slashes.The stench is overwhelming. I was reminded of Nina Jäckle’s book der lange Atem where bodies are bloated and distended, hard to identify. There it’s the Tsunami which has caused such damage, whereas here it is humankind which has maimed, shot, crushed and tortured these mostly very young people in a brutal response by the state to their demands for freedom and democracy.

The novel goes on to explore the stories of other characters introduced in that first story while always keeping our awareness on the body. So the next section is narrated by a soul hovering around his physical body, which finds itself at the bottom of a pile of bodies ‘stacked in the neat shape of a cross’ after being dumped in the countryside. We learn that this is Jeong-Dae also seeking his sister amongst the bodies and the souls and how he died. Kim Eun-sook, an older student whom Dong-Ho meets working at the gymnasium, later works for a small publishing house. She is interrogated about a translator they use and receives seven slaps to the face so hard that the capillary blood vessels ‘laced over her right cheekbone burst, the blood trickling out through her broken skin’. To put this behind her she tries to devote one day to forgetting each slap and through her attempt to forget we learn what she has been through since the uprising. In The Prisoner 1990 we hear an account of torture and brutal prison conditions from a man who shared a cell with Kim Jin-Su, another student working at the gymnasium. The particular method of torture and its physical consequences for the prisoners’ hands are clearly described. Here it is not just the physical torture they endure which is shocking but the ruined lives which follow: the men meet by chance some years later, both heavy drinkers, unable to hold down a job or relationship.

Han Kang’s close attention to physical detail-to skin, knuckle and bone- has been seen already in The Vegetarian, particularly in its section on the painting of the body. Here she also uses detail to good effect in characterisation, as in Kim Eun-sook’s take on her boss whom she does not trust ‘from close up, his open, unguarded eyes seemed unaccountably tinged with fear, and the lines circling his neck were deeper than one would have expected for someone his age’. She evokes youth and vulnerability as well as the tender mother’s eye when describing Dong-Ho ‘ There was no mistaking those toothpick arms, poking out of your short shirtsleeves. It was your narrow shoulders, your own special way of walking, loping like a little fawn’. It is through the body that she describes the unbearable humidity of the summer months: ‘the heat and humidity of an August evening pummels you… at the top of your back the sweat- soaked fabric has darkened to an inky black….the sweat clinging to the hair behind your ears crawls down over your jaw and drips onto your shirt collar’.

And there is an awareness of skin- a porosity as souls pass through the physical confines of the body to hover nearby. The horrific scene where the young machinists, defending the strikers take off their clothes in the belief that the soldiers will respect their young and virginal bodies. But there is also the feeling of solidarity evoked by skin touching-the prisoner remembers people lining up to donate blood after the massacre, singing the national anthem, ‘Those snapshot moments, when it seemed we’d all performed the miracle of stepping outside the shell of our own selves, one person’s tender skin coming into grazed contact with another, felt as though they were rethreading the sinews of that world heart, patching up the fissures from which blood had flowed, making it beat again’.

The title Human Acts seems at first to refer to the barbarity and cruelty shown by the army and police in the uprising and later violence-especially in a world where we see daily acts of barbarism via our 24 hour media. Yet the novel also contains moments of solidarity, of human goodness like the singing together of the blood donors. In The Factory Girl 2002 Lim Seong-ju, also working at the gymnasium that day, reflects on her political activism over the years and particularly on her relationship with the tireless Kim Seong-hee, a labour rights activist working to improve the conditions of young machinists. She remembers the bus full of young women workers waving their banner and singing,on their way to the main square on the fateful night of the army reentering the city. Her memories are of collective action, of unbelievable strength and solidarity. She reflects that she would have done the some again, if she were able to ‘go back’.

The author, Han Kang, was a child at the time of the uprising and has a personal connection to the events of the uprising-this is referred to by the translator, Deborah Smith, in her helpful introduction and becomes clear in the last section of the book. In this, The Writer 2013, Han Kang returns to Gwangju to find out more about the uprising and to find the grave of the boy, Dong-ho. It is a deeply moving account of her experience.

This is a powerful novel about the uprising in South Korea, its brutal repression and the long term consequences for individuals and families. But it is also about the moments of solidarity and strength which can occur. Thanks to Deborah Smith for her seamless translation and to English Pen for bringing us this work.

Advertisements Share this: