It’s night, when the city is at its best. To the brassy, aggressive strains of a jazz anthem composed by Elmer Bernstein, our point of view drifts through the glorious, desperate chaos of New York at night. Men in suits, women in cocktail dresses, stumbling into and out of nightclubs, into and out of cabs. Those who want to be seen, those who want to see. Movers, shakers, power players, hustlers, hyenas. The kings and queens, the wannabes, the has-beens, the never-will-bes. Our eye is the lens of James Wong Howe’s camera, in moody, beautiful black and white and a depth of focus that is overwhelming, like the city at night. There’s too much we can see crisply. Too many people, too many cars, too many blinking neon signs luring us into the hotspots of 52nd Street when it was Swing Street. Too much and never enough.

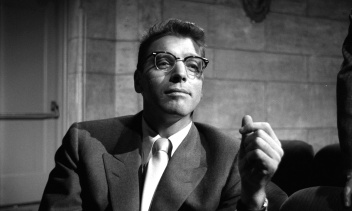

Through these dangerous waters swims JJ Hunsecker, a merciless, emotionally remote gossip columnist who can make or destroy a career with a single sentence and who relishes that power. Around him swirl a cloud of sycophants either looking to make themselves seem more impressive by association or looking to catch JJ’s eye so that he might throw a kind word the way of their new play or new client. In the middle of this pack but looking to lead the herd is Sidney Falco, a sleazy, hungry press agent with no morals, who is willing to pull any con, hustle any way he can, to claw his way out of the middle of the pack. Hunsecker is Sidney’s ticket out of mediocrity, and Hunsecker knows that. He’s not the kind of man not to use it.

Sweet Smell of Success

Sweet Smell of Success  Sweet Smell of Success

Sweet Smell of Success  Sweet Smell of Success

Sweet Smell of Success

This is the world set up in Sweet Smell of Success, a brutal, biting showbiz noir from 1957, directed by Alexander Mackendrick and written by Clifford Odets, and Ernest Lehman (who also wrote the novel on which the movie is based). It is one of the meanest films of the late noir era, full of the most cynical, misanthropic characters. And it accomplishes this without gangsters, without shoot outs, without murder or most of the accoutrements with which one usually associates film noir. It is, instead, one of a handful of noir that focus on the cutthroat nature of the very business that created it: entertainment. It stars Burt Lancaster as the vicious entertainment journalist JJ Hunsecker and, in a role so slimy that his legions of fans revolted against the besmirching of his established good looking good guy persona, Tony Curtis, as the “anything to get ahead” talent agent Sidney Falco (As JJ describes him, “I’d hate to take a bite outta you. You’re a cookie full of arsenic.”) Two New York boys — Lancaster from 209 East 106th Street in Manhattan, and Curtis the son of a tailor from The Bronx — in one of the quintessential New York movies.

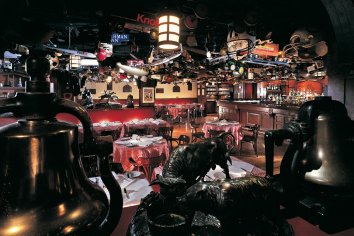

Much of the film’s action takes place in two locations. One, like many iconic spots of the city’s middle of the century, is now a Duane Reade. The other soldiers on, one of the last of these places still standing in a city that always moves forward. Sidney Falco throws himself into the sweaty, drunken crowd of the rowdy night spot Toots Shor’s while JJ, impeccably dressed and observing the world like a bird of prey, holds court in the estimable 21 Club.

Toots outside his namesake joint

Toots outside his namesake joint  The bar at Toots Shor’s

The bar at Toots Shor’s  Toots Shor’s regular Jackie Gleason with Marilyn Monroe

Nuttin’ Fancy

Toots Shor’s regular Jackie Gleason with Marilyn Monroe

Nuttin’ Fancy

Just over half a century ago, in a Manhattan that was defined by sharp suits and three-Martini lunches, there was a joint called Toots Shor’s. It was the kind of place where Joe DiMaggio would go to enjoy a drink while seated next to Jackie Gleason, where Frank Sinatra would drop in, where Marilyn Monroe could be found seated at its famous round bar. And yet, despite its place as one of the great celebrity watering holes of the Golden Age of such places, it was hardly a bastion of elegance. When I say it was a joint, I mean it was a joint, and Toots Shor, the man behind it all, wasn’t a polished member of the aristocracy looking to foster the rarefied airs of high society. If Toots Shor’s was a cocktail, it would have been a whiskey sour. And if it was food, it would have been “maybe you should eat somewhere else.”

Sure, they had a kitchen, serving up pretty standard fare for a time when fine dining was rarely all that fine: shrimp cocktail, baked potatoes, yankee pot roast. There’s a reason mid-century America is remembered for its drinking, its style, its design and architecture but not its cuisine. You didn’t go to Toots Shor’s for the food. You went there for the booze, and you went there for the atmosphere. Yeah, you wore your suit and tie or your cocktail dress (wives were discouraged, though mistresses and “broads” were welcome), but this place was all back-slapping drunks with their arms around each other (occasionally their fists in each other’s faces, but only occasionally). It was also male. Very male. Like I said, mid-century America isn’t celebrated for its cuisine. And it’s certainly not celebrated for its gender politics. When looking back on a time like this, it’s easy to find things to admire, but it’s just as easy to find things about which we should be rightly reviled, or at least thankful that their attitudes since piled into the rubbish bin of history.

Crashing Joe DiMaggio’s table at Toots Shor’s

Crashing Joe DiMaggio’s table at Toots Shor’s  Toots and Jackie

Toots and Jackie  The scene outside Toots Shor’s

The scene outside Toots Shor’s

Toots was born in Philadelphia in 1903 to Orthodox Jewish parents who didn’t call him “Toots” – they called him Bernard. Both his parents died tragically when he was a young man — his mother killed in a traffic accident while she was sitting on the stoop of their apartment when Toots was 15; his father five years later by suicide. Toots went to college, bounced into a job as a traveling salesman (shirts and underwear), and finally ended up in New York working as a doorman at some of the town’s speakeasies. At these places, he met and befriended many of New York’s celebrities, politicians, and gangsters, all of whom came together for an illegal drink or two at places like the Five O’Clock Club and Lahiff’s Tavern (158 W. 48th Street). Gregarious and capable of flattening an unruly drunk when he needed to, Toots worked his way from the doors to floor, to manager, and finally to owner when he opened his own place in the 1940s at 51 West 51st Street. The celebrities he’d befriended over the years were happy to come along, especially when it became obvious that Toots was never going to call in their tab. Or even keep one.1

Through the 1940s and ’50s, Toots Shor’s was the place. Toots described his bar and restaurant as “nuttin’ fancy.” The after-watering hole watering hole. Jackie Gleason was practically a resident there, showing up to drink away the afternoon, heading home for a nap, then returning for the late-night scene. Sinatra name-dropped the place in his duet song with Sammy Davis, Jr., “Me and My Shadow,” placing it alongside his other favorite hangout, Jilly’s Saloon. Judges, writers, stars, and mobsters flocked to Toots Shor’s, forming an inebriated brotherhood Toots lovingly referred to as “crum-bums.” But above all others, Toots courted baseball players. DiMaggio, Mickey Mantle. Well, Mickey Mantle. Joe stopped dropping by after Toots referred to Joe’s wife using a vulgar term for lady of the night. Joe’s wife being Marilyn Monroe. Joe and Marilyn would famously split after less than a year of marriage. She wanted freedom, the wild life her celebrity put at her feet. He wanted a demure housewife. Ugly though the split was, Joe never forgave Toots for insulting Marilyn. DiMaggio sought companionship in Frank Sinatra, himself going through a nasty meltdown with Ava Gardner, and probably not the best drinking buddy at the time. Sinatra’s crew, which included Jack Kennedy, also used Marilyn mercilessly during the ’50s and and ’60s. She died in 1962, the last person she talked to apparently being the one Rat Packer who seemed to actually care about her: Peter Lawford, Sinatra’s favorite punching bag and brother-in-law to JFK.

Marilyn’s table

Marilyn’s table  Toots Shor’s in Sweet Smell of Success

Toots Shor’s in Sweet Smell of Success  Toots Shor’s in Mad Men

Toots Shor’s in Mad Men

By 1962, Toots Shor’s was also gone, or at least relocated. It turned out that no matter how packed and popular your place is, if you’re not making anyone pay for drinks, it’s hard to pay the bills. Toots sold the 51st Street location in 1961 and moved to a new location at 33 West 52nd Street, an address with a storied and perfectly sordid past. In fact, Toots himself had worked there in the 1930s, when it was Leon & Eddie’s, founded by entertainers Eddie Davis and Leon Enkin and one of the most infamous places along what became Swing Street and, later, Strip Street. In the 1940s, Leon & Eddie’s catered to American servicemen about to ship out to the War and looking for one last, big fling before the slog through Western Europe. Scantily clad chorus girls, ribald stand-up comics, and flirtatious dancers were happy to send the boys off with memories to get them through to Berlin. While other former speakeasies were trying to cultivate an elegant clientele of celebrities and “cafe society,” Leon and Eddie’s was the place local businessmen, adventurous tourists, cheap hustlers, and soldiers went, “a place where they didn’t have to worry about getting the high hat” as Billboard described it in 1946. It later became famous for featuring two of America’s most famous burlesque queens: Noel Toy (a legend in the Chinatown nightclubs of San Francisco) and her infamous fan dance, and Sherry Britton, who stripped to Tchaikovsky. 2

Just when Toots found himself out at 51st Street, Leon and Eddie were looking to call it a day. Shor, who had been a bouncer at the place back in its speakeasy days, moved in, in 1961. The new Toots Shor’s operated until 1971, but the magic never returned. The 1970s weren’t the 1950s or ’60s, and a more turned on, tuned in, racially diverse young crowd was now in charge of defining the city’s sense of cool, and old cats like Toots weren’t able to run with the glitter and love brigade. That did not include old-fashioned nightspots like Toots Shor’s. Toots tried to franchise, selling the name to a management company that went on to handle TGI Fridays, but there just wasn’t much bank in a name like Toots Shor post-Sgt. Pepper’s. The space existed for a while as the New York, New York disco, home of the world’s first laser light show, until eventually the entire building was demolished. A massive glass and concrete Deutsche Bank high-rise looms there now.

Leon and Eddie’s, complete with sailor loitering out front

Leon and Eddie’s, complete with sailor loitering out front  Noel Toy

Noel Toy  Sherry Britton

Sherry Britton

Short of a whiskey and soda or Martini, about the only cocktail you’d order at Toot’s Shor’s was shrimp. Still, while researching the latest edition of the The Waldorf-Astoria Bar Book, writer/bartender Frank Caiafa came across a cocktail named in honor of Toots, though perhaps not with the character of the man or his joint particularly well reflected. According to Frank’s research, the Toots Shor as listed in the 1960 Calvert Party Encyclopedia was actually the Trilby No. 2 from the Savoy Cocktail Book, which already had a Trilby, even though the Trilby No. 2 probably predated the other Trilby, because it appeared in a 1900 manual by bartender Harry Johnson, where it was just called a Trilby — sort of like that period Spinal Tap spent touring as the New Originals because there was already a band called the Originals. Anyway…

Trilby No. 2/Toots Shor3

- 2 oz good blended Scotch (the book calls for Buchanan’s DeLuxe 12 Year)

- 1 oz Martini & Rossi sweet vermouth

- 1/4 oz Marie Brizard Parfait d’Amour

- 1 dash Pernod pastis

- 1 dash orange bittersAdd all ingredients to a mixing glass and stir for 30 seconds. Strain into chilled cocktail glass and garnish with a lemon peel.

The idea that Toots Shor would own a bottle of Parfait d’Amour, let alone drink it, is hilarious. But then again, who knows? Those guys sometimes contained untold depths. Frank Sinatra painted himself up like a sad clown on one of his album covers.

More suitable a glass to raise in Toots’ honor:

Whiskey Sour

- 2.5 oz bourbon

- 3⁄4 oz fresh lemon juice

- 3⁄4 oz simple syrup

- garnish: 1 cocktail cherry and lemon wedgeAdd all the ingredients to a shaker filled with ice and shake. Strain into a rocks glass filled with fresh ice. Garnish.

Gene Autry visits ’21’ in the 1950s. Photo courtesy 21 Club

Gene Autry visits ’21’ in the 1950s. Photo courtesy 21 Club  The bar at 21. Photo courtesy 21 Club

The bar at 21. Photo courtesy 21 Club  Sunset on Swing Street. Photo courtesy 21 Club

The King of 52nd Street

Sunset on Swing Street. Photo courtesy 21 Club

The King of 52nd Street

While Sidney was pushing through the drunks at Toots Shor’s to the sound of the Chico Hamilton Quintet playing in the corner, JJ was presiding over a more refined but no less frenzied scene a short distance away at the ’21’ Club, which despite the changes in the city and that block in particular over the years, remains a stalwart presence on the block that used to swing but now mostly manages investments and whatever else it is bankers do in those austere, anonymous skyscrapers. Located at 21 West 52nd Street and opened (as a speakeasy, naturally) during a wild party on Dec. 31, 1929, it’s one of the city’s few remaining establishments that expects you to dress up; jeans are forbidden, and a jacket is required (though they relaxed the rule about ties in 2009). Before settling in at the address that would stay theirs for decades, 21 bounced from location to location. Originally, it was located in Greenwich Village as far back as 1922, when cousins Jack Kreindler and Charlie Berns opened the first incarnation, known as the Red Head. They later moved to Washington Place and changed the name to Fronton, and then moved again to 42nd St., where it was known as the Puncheon Club. It was this version that saw the introduction of a more elegant atmosphere, which stayed in place when they finally moved to 52nd St and christened the new location Jack and Charlie’s ’21’.

“A more elegant atmosphere” doesn’t mean a chaste atmosphere. This was still Prohibition after all, and what went on at 21 was still illegal. Like many speakeasy proprietors, Jack, Charlie, and their staff devised a number of ingenious contraptions to help them avoid getting busted during raids. There was a lever near the bar which, when thrown, would quickly and efficiently tilt the shelves so that all the booze dropped down a chute and into the city sewer while the bar itself smoothly rotated to a hiding place behind the wall. There was also a secret door that led to the club’s secret wine cellar. After Prohibition, the sophisticated air and clientele the cousins had cultivated during their illicit years stayed loyal. And, remarkably, they’ve remained loyal ever since.

The Nixons at 21. Photo courtesy 21 Club

The Nixons at 21. Photo courtesy 21 Club  Burt Lancaster’s JJ Hunsecker holds court at 21

Burt Lancaster’s JJ Hunsecker holds court at 21  21 Club memorabilia collection. Photo courtesy 21 Club

21 Club memorabilia collection. Photo courtesy 21 Club

When JJ Hunsecker used it as his office away from the office in Sweet Smell of Success, ’21’ was a hive of activity. “Though none of our associates date back quite that far, we have learned over the years that the buzz in Sweet Smell of Success is an accurate portrayal of the time,” says Avery Fletcher, ‘current Director of Sales and Marketing for ’21’. “This was an age of 2, 3, 4 Martini lunches and lots of business in the dining room. Each table had a phone jack nearby and writers, advertising executives, and celebrities would stay for hours with assistants running in and out all day long.” It wasn’t a quiet, romantic night out, but if you were making the scene, or like JJ breaking someone’s scene, ’21’ was where you staked your territory. “Still the snappiest restaurant in New York,” wrote Spy magazine in 1960, in a description of the place that perfectly captures its appearance in Sweet Smell of Success. “A caste system operates in this plush spot separating the big from the small and the biggest from them all.” 4

Sidney Falco is one of those kids looking to sit at the big table, at JJ’s table. Ostensibly, it’s because Falco wants his latest client to succeed, and a kind mention from JJ would pretty much cement that. But as the film progresses, it becomes a lot less about the client succeeded and more about Sidney’s obsessive drive to make it, for he himself to succeed. JJ, recognizing that whiff of desperate fear like any well-honed predator would, is more than happy to dangle the bait for Sidney and offer him a Faustian deal. It might destroy a couple lives, and it would definitely blacken Sidney’s soul, but hey. What’s that compared to the sweet smell of success? If one wants to scour away some of the romanticization of the Mad Men era, which wasn’t exactly as great a time for many as it was for white guys, Sweet Smell of Success goes a long way to poking that seedy underbelly and skewering “dog eat dog” machismo.

Sweet Smell of Success

Sweet Smell of Success  Sweet Smell of Success

Sweet Smell of Success  Sweet Smell of Success

Sweet Smell of Success

Toots Shor’s was a place for a beer and a whiskey and a plate of grub, and nearby Jilly’s slung cheap, hearty Chinese food, but ’21’ was where you went for an actual good meal. They prided themselves on their food and have worked for some 85 years to maintain that reputation. Similarly, they’ve sought to keep pace with the changing face of cocktail culture, from the mid-century classics like Manhattans and Martinis that would have been the lifeblood of Hunsecker and his crew to the craft cocktails that defines the landscape today.

“We aim to blend the classic with the contemporary for our cocktail selections,” says Avery Fletcher. “Seasonal creations like the Iron Gate Old Fashioned, Jam Mule and Secret Password feature housemade gastriques, syrups and bitters.” Though, she adds, people today expect a certain level of old-school tradition from ’21’, so they’re not going to stray too far from the classics. “You won’t find dry ice and mystery pearls in our cocktails.”

She says if there’s one cocktail, besides the aforementioned Martini and Manhattan, that characterizes the ’21’ Club of Sweet Smell of Success’ era, it’s the Southside:

Southside

- 2 oz Plymouth gin

- 1 oz fresh lemon juice

- 5 mint leaves

- 1 oz simple syrupIn a shaker, muddle the mint and lemon juice. Add the remaining ingredients, fill with ice, and then shake and strain into a chilled Martini glass. Garnish with a mint sprig or lemon twist.

Similarly, the atmosphere at ’21’ Club has calmed down a little, and alas, the table side phone jacks are gone. “The technology has changed with cell phones replacing the table side plug-ins and perhaps the pace is a little less frenetic,” says Fletcher, “but ’21’ today is still a place to see and be seen as well as the site of many business deals. World leaders, artists and actors, and business moguls can still be seen here any day of the week. Of course, today, you will also find local New Yorkers and visitors who have come to experience the storied history.” Which is true. While people wait months and years to get a reservation at whatever the new trendy restaurant might be, it’s easier to secure a table at a classic like ’21’. When I had dinner there, I didn’t spy any titans of modern culture (to be fair, I would recognize more people from 1957 than 2017), but I did bond with an older gentleman who was initiating his college-age grandson into the family tradition of enjoying a meal at ’21’. Also, he was explaining to the younger generation the importance of the dress code and why it’s nice to have some places that still enforce standards of attire.

In its long history, 21 has played host to writers, movie stars, singers, and every American President since Franklin Delano Roosevelt except for George W. Bush. In fact, the club was recently dragged into a brouhaha when newly minted President-elect Donald Trump ditched the press corp and snuck out (or at least tried to) for a private meal. His destination? ’21’ Club, where so many other presidents and dignitaries and dukes and duchesses have enjoyed a meal beneath the dining room’s iconic ceiling of knick knacks and ephemera, including a model PT boat from JFK. “Prohibition raids, Hemingway escapades, Marilyn Monroe and Joe DiMaggio, a gift from JFK,” reflects Fletcher, “Jackie Gleason swapping a model train for the pool cue from The Hustler, Gordon Gecko (Michael Douglas) declaring ‘Lunch is for wimps’ in Wall Street, Nelson Mandela, Bette Midler, Jimmy Fallon crossing the room to offer Wes Anderson a taste of his Chicken Hash.” It’s hard to think of a place where so many disparate temperaments, political alignments, and types of people have all passed through the street side iron gates flanked by a retinue of ever-vigilant jockeys.

Sweet Smell of Success

Sweet Smell of Success  Sweet Smell of Success

Sweet Smell of Success  Sweet Smell of Success

Sweet Smell of Success

As, one by one, the famous clubs of Swing Street began to die off, ’21’ weathered the storm, thanks perhaps to the fact that they proved a little more competent in managing their money than had, say, neighbors like Toots Shor and Jilly Rizzo, both of whom could never seem to stay out of debt or off the IRS shit list. The food was also much better at ’21’. Fletcher adds, “Our core tenants of fine cuisine, wine and service in a sophisticated fun environment will never change. However, we do continually adapt to the evolving wants and needs of our guests. Whether it is integrating contemporary mixology or culinary techniques into our menus or being one of the first luxury restaurants in NYC to have a Facebook page.” Even as skyscrapers sprouted up around them, replacing the old establishments, ’21’ remains “the lone reminder of Swing Street’s previous self; standing tall figuratively though dwarfed physically.”

By the time Sweet Smell of Success hits its closing shot, as the mournful menace of the Chico Hamilton Quintet’s “Night Beat” signals a ceasefire to the evening’s battles, the viewer like the characters have been through a ringer, and no one emerges unscathed. Lives are ruined, perhaps more and different lives than JJ Hunsecker hoped. But lives have also found the inspiration, however ugly the source, to be reborn, to peel themselves away from the pack and strike out in search of something new. As the sun rises on the streets of New York, littered with the casualties of another night of revelry, deal-making, and sin, the grime and filth still seems somehow…admirable? Maybe not? A red badge of courage? Perhaps. And whoever didn’t survive the night? Maybe they’ll be remembered. Maybe not. Because it all starts again later that evening, some players returning, others taking the field for the first time. That’s the game. Who wants to live in a New York that stands still? And even if Toots Shor’s is gone, even if Swing Street is gone, even if ’21’ Club is one of the lone remaining guardians of that wild, damaged, enthralling Swing Street era, it’s hard, if you really have the city in your blood, not to stand there surrounded by all the concrete and glass and human wreckage and say to yourself, like JJ Hunsecker, “I love this dirty town.”

NotesThis article originally appeared on Alcohol Professor.

Share this:- More