Intro by Luke Wigren & Chul Gugich | Interview by Luke Wigren

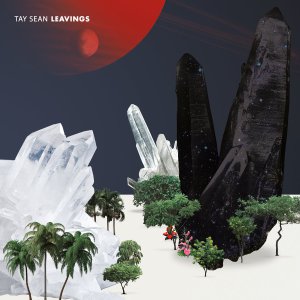

Tay Sean is a rapper-slash-producer from Seattle, whose debut solo album, Leavings, works on the fringes of hip-hop. Manipulated found sounds, exploratory inward-facing raps and drums as hard as compressed carbon, are bound with unpredictable futurism and modern turnt sensibilities.

To label Tay’s practice as “fringed” or “outside of center” is to also recognize the current state of his home city’s hip-hop scene. Due primarily to economic and cultural displacement, the city is experiencing the suburbanization of both its hip-hop style and creators. The cold efficiency of an increasingly technocratic city has led to the standard charge of gentrification on view in most of America’s major urban centers.

In January 2016, Seattle’s venerable (and lone) “urban” radio station, KUBE 93, moved south to Tacoma, to lesser wattage and a smaller — and decidedly darker-complexioned — audience. The whooshing sound that echoed through Seattle’s downtown core in the wake of KUBE’s departure, was a new, more pop-oriented cast of local artists rushing in to fill the vacuum. Unsurprisingly, the demographics of fans who turn out to those artists’ shows has also shifted to a younger — and decidedly lighter-complexioned — audience.

Through this change, Tay Sean has remained artistically unfazed. Eight years ago, he was the ringleader of the burgeoning Cloud Nice movement, a forward looking and vaguely futuristic crew of blunted rap realists that hovered above the proletariat camp overseen by the now disbanded Massline collective (Blue Scholars, Common Market), and the aspirational street sensibility of the early Sportn’ Life Records (Dyme Def, D. Black). These days, Tay Sean is a stalwart in Seattle rap, aligning easily with the hazy trap enlightenment of Moor Gang (Jarv Dee, Gifted Gab) and the city’s funk-infused, afro-futuristic Black Constellation collective (THEESatisfaction, Shabazz Palaces).

Through this change, Tay Sean has remained artistically unfazed. Eight years ago, he was the ringleader of the burgeoning Cloud Nice movement, a forward looking and vaguely futuristic crew of blunted rap realists that hovered above the proletariat camp overseen by the now disbanded Massline collective (Blue Scholars, Common Market), and the aspirational street sensibility of the early Sportn’ Life Records (Dyme Def, D. Black). These days, Tay Sean is a stalwart in Seattle rap, aligning easily with the hazy trap enlightenment of Moor Gang (Jarv Dee, Gifted Gab) and the city’s funk-infused, afro-futuristic Black Constellation collective (THEESatisfaction, Shabazz Palaces).

At various points in its 12 tracks, Leavings sounds like the connective tissue between all of these Seattle rap movements. It almost certainly wasn’t Tay Sean’s intent, but the album serves as a culmination of many hip-hop viewpoints, and a strict departure from what Seattle rap is currently undergoing. A few weeks ago, as a rare snowfall began in the city, I met with the artist to discuss his new record in the Beacon Hill neighborhood, in a home that will soon be demolished for luxury apartments.

Luke Wigren for the Coastal Elite: Introduce yourself and introduce where this record comes into your life right now.

Tay Sean: I’m Tay Sean. I’m a 29 year old adult rapper. The record Leavings is kind of my first full length thing. Well, I guess it’s my first solo project that’s really a full project and that’s coming off of being in a few different group settings. I had my first band with Helladope, and then I did Helluvastate, which was kind of a mashup group with my boy Thad from State of the Artist, and then I was in a band called Kingdom Crumbs. That period was maybe six or seven years and so now I did a solo project and that’s what Leavings is. That’s where it fits into my musical chronology.

CE: You’ve allowed the solo project a long time to gestate. You’ve done a lot of music before, but this is your first proper solo introduction. Why now?

TS: My band broke up. My band broke up man so I had to do something [laughs]. Nah, you know there’s a part of me that’s always wanted to, you know, see what my music sounds like, to see what my solo stuff sounds like. Also, I think part of it was exploring the feasibility of doing something solo because when you’re working with a lot of different people that’s something you got to take into account, you know. It’s hard to manage everybody’s time, get the rehearsals done, get into the studio to make new music. I thought I may as well just put out some of my solo stuff. Pretty much how that goes.

CE: What were the sorts of ideas that you were tackling on this record? What philosophies were you thinking about?

TS: I mean I don’t think I ever really set out to do a conceptual album. Some people have said it sounds like conceptual album but I don’t ever really set out to do it like that. I just make songs. It’s a part of living life for me, like some ideas — some things that I feel, some feelings — express themselves in song, and some of them stay in my head forever. Some of them I go in the studio and I make. And the ones that I like, I like to share. Basically. So I guess if there is an overlying or underlying theme or whatever, it would just be that this was where I was at at the time. Those are the things I was thinking about at the time. It’s not like a contrived idea about what this album should be about.

CE: I know you have a family now. Do you think it made it on your record?

TS: Yeah, absolutely it made it on my record. I have a wonderful family. I don’t really know how to answer how that influence wiggles itself onto the record. I think, though, something about having kids, having kids look up to you. My girl who I’ve been living with for six years has two kids, one of them is 18 years old and the other one is 10, and we’ve got a big house and we’ve got kind of like an open door policy, like all the homies can fall through. It’s a safe place for the homies to kick it. And just having kids look up to you makes — at least for me — it makes me conscientious about what kind of things I’m representing and what kind of things I want to stand for. You know what I’m saying? So I think that not in an intentional way, again it’s not something I overtly decide, but I think it has an effect on the type of things that I talk about, but more so just on the type of person I am.

CE: What’s that yell at the end of “Dawn Chorus?” To me it sounded like someone giving birth or someone grieving?

TS: Oh someone crying… So that song is about dying. It’s about getting shot up. In my neighborhood it’s not uncommon to hear gunshots. I mean just a couple weeks ago there was a shooting on my block, right. Like, I come home, and I’m trying to go home, and I had to go around the block cuz there’s a shooting and so the idea was: I’m never the victim there, nor do I know the victim, but it’s always like one degree of separation like I know someone that knows the victim. And so in a sense it was just me wondering, “What’s that feeling to be dying?” What would you think about?

CE: And that’s what you’re grappling with in that video, right? How did that video come to be?

TS: This cat Noah, the director Noah Porter, hit me up and was like, “Hey I have an idea for this video and I want to do a mash-up of these two songs [“Supramundane”/”Dawn Chorus”]. What do you think?” I said, “I’d love to do a video, I don’t have any money though. I spent it all.” [laughs] He said, “That’s cool man, we’ll make it happen. Here’s a treatment.” And we kind of worked on the treatment a little bit together. And then he and the Director of Photography, Scott Uyeda, came up to my house and just stayed overnight. We shot over the course of two days. It was really cool, like we didn’t really have a lot planned out. We just grabbed pieces, like people and locations, from my neighborhood — which is what inspired the song, right — and we pulled them into the video really ad hoc and it felt really good. It felt really natural. My homie’s Grandma is in the video. One of my best friends, Jarv Dee, is in the video. The homies let us just use their house. Someone came through with the whip. It was really cool how it all came together. I’m really happy we did that.

CE: Tell me the story about how that song came to be.

TS: How that song came to be was like, I was drunk as fuck at four o’clock in the morning one night. I was at the house where we shot the video. My guy Mikey who was in Kingdom Crumbs used to live there. We was drinking a bunch of beer or something and I came home hella late, a little bit drunk — you know I live just right down the street from there. So I get back to my spot, smoking cigarettes on the porch, and I start hearing the birds outside and it must have been summertime or something and the birds outside were just going hammy, just loud. [whistles] And I was like, “What the fuck!” I had never heard that before. I noticed that this bird was making this sound [whistles]. And this one’s over here [whistles]. And I was like, “Ooooh that’s beautiful,” ‘cause they was almost making a beat. So I recorded it. Then later I went down to the studio and made a beat based on what I heard. I looked it up [what the birds were doing] and it’s called a “dawn chorus.” And then later on I thought that the urban representation of this dawn chorus is these gunshots that I keep hearing and so the percussion aspect of that beat is gunshots and then that kind of fed into what that song was going to be about. It was just kind of putting myself in the shoes of one of those riders or something. That’s the story of that song, I mean there’s a story behind every song.

CE: I feel like there’s lots of stuff on your record that really taps into the beyond, you know like the song “Higher Vibrations” just turns into this big explosion of sound. If you could — I know you have ties to Shabazz Palaces and the Black Constellation — just explain a bit about the metaphysical realms that you approach in this record.

TS: That’s really hard to answer, “What I feel my connection is to that music?” because I know that I do feel a very strong connection to that music. “Why?” is something that I don’t really know. I don’t know if I can answer that flat out.

BenadriLL: I think it’s cuz you’re from space.

TS: We’re all from space. In fact, we’re all in space. We are right now hurtling through space on a spherical spaceship as part of a vortex that’s our solar system. So we’re all from space. I think maybe part of it is all of these artists seem to be concerned with their relationship towards others on that spaceship, towards the spaceship itself, and towards the rest of the space both without and within. So I think those are [the] things about those artists that really intrigue me, and have been a spiritual beacon for me throughout my life.

CE: How then — and I heard Maikoiyo Alley-Barnes [of Black Constellation] talk about this at the Frye Art Museum’s Young Blood exhibit — but how has the Seattle ecosystem influenced your music?

TS: Again, the “how” is hard to answer definitively, but I know that some aspects of how it could do that is like, we live in a place that’s really surrounded by a lot of natural creation as opposed to man-made creation and I would even say that man-made creation is, in a sense natural, but I would also contend that man-made creation has a very different aesthetic — very different. It’s a lot of vertical planes. Flat plains. Geometry. A really precise aesthetic. Whereas nature has a very different organic kind of a feel to it, like the look of it. I really am in love with the juxtaposition of those things. But I also think that the way that the Earth itself kind of vibrates has an impact on how a person is, or just what you look at and absorb. It has an impact on how you are, or how you navigate life, or how your music sounds, if that’s what you’re talking about.

CE: Yeah, Maikoyo talked about how the natural elements that influenced himself and Seattle brothers Noah Davis [visual artist] and Khalil Joseph [director of Beyonce’s Lemonade] were the smell of the cherry trees in the Central District, or playing on the beaches of Lake Washington, and Ishmael Butler [Digable Planets, Shabazz Palaces] talks about how Seattle’s lush greenness creates a sort of mysticism.

TS: I agree, yes.

CE: I pick it up in your music, too. What kind of legacy do you want your music to leave not just in Seattle but beyond?

TS: What I really want to do is not leave a legacy of music. I want to capture what you was talking about before with the smells and… You know how they have Instagram? I wanna make an app where you can capture a smell and then share that with people. Be like “Yo, I was walking this morning and it smelled so crisp and delish”…

BenadriLL: Or, you walk by the “Old E” bus stop, it smells like beer.

TS: [Laughs] This is the back of the 36. I call this one “back eau de 36”. [laughs] Nah, sorry, what was your question again?

CE: Maybe a better way to ask that is like, “What phase of artist are you in?” because you’ve evolved certainly over the last ten years. Where are you at now?

TS: I don’t really know, man. I don’t really think about it that way. I don’t think about the artistic legacy that I’m leaving behind. I’m just doing my thing, man. I’m just living and making music is a part of that. So i don’t really have a goal here. I’m not really trying to leave having anyone say, “Tay Sean was responsible for X, Y, Z.” I ain’t really worried about that. [laughs] I’m just living and making music. It would be nice to find outlets where I could be more useful to society, more useful to my community, a better person. You know what I’m saying? That’s more important to me than my musical legacy.

CE: Yeah, along those lines, I saw you perform recently at the Black Panther 50th Anniversary events in Seattle. How did that come to be and how did you feel you could lend your music?

TS: That’s easy. The legacy of the Black Panthers is something that is always, again just like Shabazz Palaces’ music, or any of these artists behind me [waves hand to records by THEESatisfaction, John Coltrane, Roberta Flack], that legacy, that energy has always resonated with me. One of my best friends is the daughter of Aaron Dixon — I see you have his book on your shelf — and she helped organize that event and she knows that I’m passionate about that history and about the future too. She asked me and I wouldn’t pass up an opportunity like that.

CE: At that event your new baby was in a stroller in the crowd. What was it like to have your child sitting in the audience there? How does that feel?

TS: Uhh, I don’t know, to be 100% honest. My answer is not going to be really interesting — it just feels regular to me. It doesn’t feel… I’m not necessarily in awe by that. It feels really regular for me to have a child. You know even though it’s my first child, it feels regular as hell. Being at the Black Panther 50th anniversary, performing there, having my baby there, it feels regular. It feel like that’s how it’s supposed to be.

CE: How did your baby react?

TS: I think when I was performing she was making some kind of noise. I think she got excited after one of the songs and then started crying after another song. I think she went up the stairs and cussed out the sound guy too. She’s like, “Cut it up.” I don’t know. [laughs] She’s really in touch with music. I think most children are. She likes when I sing to her. I’ll just make up songs and sing them to her. Or, when I put on some Stevie Wonder and sing some Stevie Wonder to her, she likes that. I think that may have been one of the first times she ever saw me do a performance though. It may be the first time.

CE: “Leavings” — what is it, how did it come to be the title? And what does it mean in context of the record?

TS: That’s a great question. I think the title has a few different meanings for me. But, you know, you keep bringing up Maikoiyo, and Maikoiyo actually inspired the title. He was talking to Jonathan Zwickel in an article and was criticizing the way people talk about art. They focus so much on the product, not the movement, not the energy, not the process that it took to bring the person to that point. And he said something like, “You just scratching the surface, just scratching the peel, scratching the surface like a mosquito bite.” And he said like, “What you’re looking at man, that’s just the ashes, that’s just the leavings. That’s just the remnants of the process.” And I think that my view of art and my view of music is very similar. I think that I was waiting for someone to articulate it in such a way and he did, so when I read that immediately I said, “Leavings,” that’s what I’m gonna call it. But it also has this… This kind of double meaning of departure of going somewhere. And I think that musically I’m trying to go somewhere else. You know what I mean? A lot of people have said that my music sounds like a critique of other music or of values, because I’m trying to leave and depart from those mundane things, at least with music. I think that music has this kind of supernatural power to do that. And that’s how I like to practice music, with that sort of intention. So yeah. Leavings. [laughs]

CE: Sweet man. Thank you. Anything more to add?

TS: Nah, just “Thanks” — it’s like when I go to the barbershop. It’s like therapy. I get a lot of shit off my chest. You ever do that? You go to the barbershop and you’re like, damn I didn’t know I could talk this much. [laughs]

Advertisements Share this: