by Rhea Sugwekar

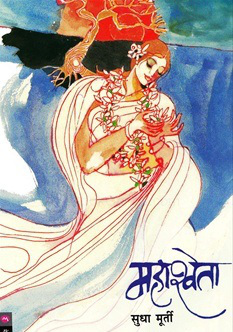

I don’t know where this book came from in my library. No jokes. It’s just been one of those pieces of literature that you’ve just somehow always had lying around, always present within the line of your sight, forever there but never acknowledged. And it’s not like I didn’t ask around, either.

“Nope, not mine. Don’t know who bought it. Ask ajji,” Mom said.

Alright, I thought, I’ll ask grandma and see. It has to be hers, although it does seem funny that a woman entirely distanced from the English language would ever buy a book written in it. I shrugged it off. Maybe she’d felt adventurous that day.

“Why would I buy a book in English?” Grandma said.

“But ajji, dad doesn’t read Sudha Murty and I’m pretty sure ajoba doesn’t, either.”

I asked the two of them anyway: I was right. Neither of the father-son duo had bought it.

Oh well, I thought. Might as well give it a read.

Right away I noticed the simple, humble design of the book. It’s the perfect size and width for a book that was picked up to be read for leisure, a friendly 171-page long story.

I have always had immense respect for Sudha Murty as a writer and as a personality: deciding to read the book wasn’t even a decision per se–it was almost obvious.

The story starts off when the protagonist, a young, beautiful (as is specified repeatedly throughout the book) and aspiring doctor named Anupama, meets the debonair, ideal and loaded Dr. Anand Rao. They have a fairytale love story and everything seems hunky dory for a hot minute.

Everything comes crashing down when Anupama realizes her husband is irrationally obsessed with societal standards of outer beauty, a fact she soon learns is a Rao family trait. A few months down the line, Anupama develops leukoderma (or vitiligo), a perfectly harmless skin condition which sends her entire life into a whirlwind of agony and trauma–both mental and physical. Coupled with a racist, regressive and extremely problematic mother-in-law, a sister-in-law who is no better, and an estranged husband who has fucked off to England for his “further studies” and who has completely cut off all communication with her post gaining knowledge of her condition, Anupama is almost driven to the brink of suicide when even her own family refuses to help her. Gathering herself, she leaves Dr. Anand and his family behind, and moves in hopes of a fresh start to Mumbai, where she begins working as a lecturer.

She meets Dr. Vasanth whilst living there, with whom she develops a deep friendship. He eventually proposes to her, but her life and the experiences that came with it have taught her a major lesson: that she never wants to be entwined within the cycle of husband and family ever again.

I read this book when I was in the eleventh grade, a young feminist in the making. Funnily enough, when I re-read this book a while back to write this article, I discovered lots of issues and red flags that I now know are problems in the first place.

To quickly summarize in brief what I thought was irrelevant and kind of problematic in the book the second time around, I would say Murty has given unnecessary importance to the protagonist’s “beauty”. Yes, I understand that it’s for the sake of the story, but the treatment that Anupama receives is undeserved, wrong and shockingly racist even if she wasn’t conventionally beautiful. Domestic and mental abuse is uncalled for in any given case, and the appearance of the victim is hardly relevant to the crimes committed and therefore should not affect the nature of the treatment received. There’s a lot of ado over Anupama receiving this abuse and how even though she has her beauty, she is still tormented and subjected to pain. Now, whether Murty meant to do this or not is still up for questioning.

Secondly, at the beginning of the book, Dr. Anand arrives at a colleague Dr. Desai’s house, to talk about Anupama, who is a mutual friend at the time. This is when Dr. Anand has realized that he has feelings for her, and therefore wants to get hitched.

Expressing concern about her singledom, Dr. Anand worries that “a beautiful girl like Anupama might have been ‘booked’ long time ago.”

And this is verbatim.

Booked? Last I checked, I wasn’t a fucking movie ticket to be “booked.” Plus, why would Dr. Anand go to his colleague to ask for Anupama’s hand in marriage? Aren’t you a well-educated doctor who should umm, I don’t know, kind of be above such formal trivialities, as though Anupama, a whole entire human being who has a perfectly sound brain that helps her make decisions, won’t be able to let him know how she felt about him her own damn self? Where is the logic? I’ve been searching for 5000 years now.

Lastly, towards the end of the book, there’s a scene in which Dr. Anand finds an old letter written to Girija, his sister, from a person called Vijay. In the letter, Vijay talks about the nights that he and Girija had spent together and of their intimacy. Dr. Anand is said to be shocked when he finds out that his own sister has had premarital sex (oh my god!) and that too, casually. (faints)

Here’s where Murty’s old-fashioned conditioning comes into view. I read ahead, hoping that maybe she’s justified Girija’s behaviour with, you know, the obvious idea of a woman’s right to sexual freedom…but no. The very concept of a casual relationship involving sex is still held to be taboo in a book that seeks to talk about the right of women to make their own choices in life irrespective of what society may say. That’s where I felt a little bit of a “Hold on, what now?” come up straight away.

But going back to my initial reading experience, as incredibly privileged first-world people, it’s sometimes hard for us to acknowledge and realize that there are many mini-worlds in our immediate desi society that still cling on to their conservative roots for dear fucking life. I was one of them, all the way back in 2012. Sure, I knew all the basic principles and concepts that qualified me as hashtag woke, but I still had a long, long way to go. So I hope you’ll understand when I tell you that this book totally expanded my perception of the sexism, misogyny, casteism and the rampant racism that so resides in our beloved Bharat.

I read this book through and through with nothing but sympathy for our girl Anupama right here–obviously, given her situation. I devoured this book in one sitting. It has a quality that leaves you wanting more, maybe a quality that Murty has in her writing itself (her other book, Wise and Otherwise, had the same effect on me). However, the idea that there are people–educated, “mature” people that still associate outer beauty and skin colour as the be all and end all to a woman–even in today’s day and age completely baffled me. Now when I look back on it, it comes as no surprise, but this was a complete tabula rasa situation for someone who had only recently realized that she’s a feminist. I had a long road to walk.

Probably one of the biggest lessons this book taught me was that education does not equal basic human decency. The most respectful person you’ll ever meet could be an illiterate househelp and the most outrageous dick of a person could have a fucking PhD. Oftentimes I hear my family talk about people who have said or done something sexist or racist and the likes, and usually the comment followed right after is “…and they’re such an educated person! I can’t believe they’d do that!” Pfft. Since when does being educated automatically mean you’re a decent person?

Anyway, this book reaffirmed that belief in me. Dr. Anand ghosts on our homegirl Anupama big time, to the point where he suddenly has this ~realization~ that “Wow, I married this woman and fuck, I HAVE RESPONSIBILITIES AND SHIT” after he sees an old couple walk into his clinic for help while he’s in England. The wife is wheelchair-bound due to the loss of her legs in a car accident, and her husband has brought her to Dr. Ass–sorry, Dr. Anand for medical assistance. When he asks the old man how they’ve managed to stay married for so long in spite of, you know, her situation, the man simply states that they’re God-fearing people, and since he vowed to her that he will love and help her during sickness and in health, it’s his duty to be there for her during her times of hardship. This suddenly lights up the narrow-minded darkness in Dr. Anand’s brain and he returns to India to apologize to Anupama–except he has no clue as to where she is anymore.

After a lot of searching and borderline stalking, he finally meets her in her apartment in Bandra. She, of course has a couple things to say to him, all with more than good enough reason. After her (justified) rant, dudebro still hopes she’ll come back to him and forgive him after all the shit he’s put her through. Obviously she tells him to stick it where the sun don’t shine, and he leaves.

In the end as I was done reading this book, one of the few things that really satisfied me was the fact that even though Dr. Vasanth is all sorts of goals for her, Anupama is let live by Murty, immersed in her freedom as a single woman. It would’ve been easy (and predictable) for Murty to have Anupama wed Vasanth and live a happily-ever-after, but she reasserts the “radical” idea that a woman can live all by herself. It also pushes the incredibly new-age and amazingly astounding idea that may or may not send 90% of Bollywood scripts into complete shit: that a guy and a girl can be just friends.

All in all, although there are a few potholes when it comes to how the characters are written and the choice amounts of adjectives used to describe Anupama (as very passionately mentioned at the beginning of this article), it’s kind of understandable that Murty would write a story like this, given the fact that she comes from a time and era where feminism in India was only in its formative years, with very, very basic ideas of where emancipation for women (and all those who identify as such) would begin and therefore, grow.

Share this:

- More