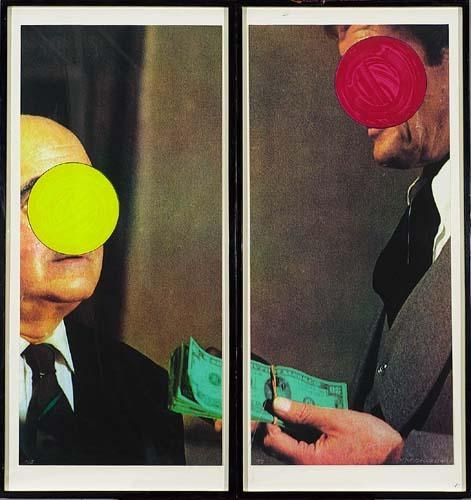

Money, With Space Between by John Baldessari

Money, With Space Between by John Baldessari

“For me, the litmus test is always language,” George Saunders told Charlie Rose in a recent interview. “If the sentences are kind of jangly and interesting, then I know how to proceed.”

Saunders composes stories syntactically: his themes and plots and characters emerge from the right jangle, the right discordant note that simultaneously pleases and disturbs. This technique shows in his latest collection Tenth of December, a showcase for Saunders’s estimable verbal prowess and a reminder that he is one of America’s preeminent satirists.

Tenth of December also reveals some of Saunders’s limitations, the biggest of which is that he seems to write the same few stories again and again. Granted, these stories are sharp, funny, puncturing criticisms of American life—satires of corpocracy and the ways commerce infests language (and hence thought); satires of how late capitalism engenders cycles of manufactured desire and very-real despair; satires, ultimately, of how we see ourselves seeing others seeing us in ways that we don’t wish to be seen. Perhaps Saunders writes the same plots repeatedly because he thinks we need to read them repeatedly—and there’s certainly pleasure and humor and pathos in Tenth of December—but there isn’t any territory explored here that would be unfamiliar to anyone who read CivilWarLand in Bad Decline or Pastoralia.

Take “Escape from Spiderhead,” one of the stronger entries in December. This is pure Saundersville, a story nudging weirdly into a skewed future that might come too-true too soon. Said spiderhead is a prison command center where wardens subject their inmates to language and desire experiments, using drugs like “Verbaluce™, VeriTalk™, ChatEase™” (lord does Saunders love incaps) to manipulate the prisoners’ minds and bodies alike (all with consent, of course).

The story is a biting and often painful exploration of how our desires and actions might be constrained and controlled by others. It’s also an excellent excuse for Saunders to flex some of those verbal muscles of his:

He added some Verbaluce™ to the drip, and soon I was feeling the same things but saying them better. The garden still looked nice. It was like the bushes were so tight-seeming and the sun made everything stand out? It was like any moment you expected some Victorians to wander in with their cups of tea. It was as if the garden had become a sort of embodiment of the domestic dreams forever intrinsic to human consciousness. It was as if I could suddenly discern, in this contemporary vignette, the ancient corollary through which Plato and some of his contemporaries might have strolled; to wit, I was sensing the eternal in the ephemeral.

“Escape from Spiderhead” is one of several tales in December that ultimately posit selflessness and empathy as a metaphysical escape hatch, an out to all the post-postmodern awful. It’s a near-perfect little story, which is why it’s too bad when Saunders essentially repeats it (right down to the Verbaluce™/amplified language conceit) in “My Chivalric Fiasco.” (Perhaps “My Chivalric Fiasco” was necessary though; it provides the sole “weird theme park” story requisite to any Saunders collection).

An equal to “Spiderhead” is “The Semplica Girl Diaries,” the collection’s strongest condemnation of how capitalism engenders bizarre ethical positions within families, between neighbors—and even countries. The longest story in the collection, “The Semplica Girl Diaries” purports to be a harried middle class father’s diary, a conceit which gives Saunders plenty of space to jangle.

Our poor narrator just wants to keep up with the Joneses, a serious character flaw that often results in hilarious hyperbole. He takes his family to the birthday party of his daughter’s classmate. This classmate’s family is wealthy, perfect, glowing, healthy, innovative, happy:

Just then father (Emmett) appears, holding freshly painted leg from merry-go-round horse, says time for dinner, hopes we like sailfish flown in fresh from Guatemala, prepared with a rare spice found only in one tiny region of Burma, which had to be bribed out, and also he had to design and build a special freshness-ensuring container for the sailfish.

Set against such a pristine backdrop our hapless narrator’s own life seems stressful and shabby:

Household in freefall, future reader. Everything chaotic. Kids, feeling tension, fighting all day. After dinner, Pam caught kids watching “I, Gropius,” (forbidden) = show where guy decides which girl to date based on feeling girls’ breasts through screen with two holes. (Do not actually show breasts. Just guy’s expressions as he feels them and girl’s expression as he feels them and girl’s expression as guy announces his rating. Still: bad show.) Pam blew up at kids: We are in most difficult period ever for family, this how they behave?

I love how Saunders works I, Gropius in there—his dystopian touches work best when they are simultaneously over-the-top (idea) and graceful (delivery of idea). These moments of humor don’t deflate the extreme anxieties that “The Semplica Girl Diaries” produces; rather, the humorous, hyperbolic eruptions add to what turns out to be a horror story.

Like the narrator of “The Semplica Girl Diaries,” the eponymous would-be hero of “Al Roosten” is painfully attuned to how others might/do see him. “Al Roosten” is one of several of December’s exercises in how we see others seeing us (set against the backdrop of how we desire others to see us, etc.). The story starts at a charity auction where local businessmen are being auctioned off (including Roosten’s rival Donfrey—an echo of Emmett) and then heads precisely nowhere (or rather, remains entirely in poor Roosten’s skull). First paragraph:

Al Roosten stood waiting behind the paper screen. Was he nervous? Well, he was a little nervous. Although probably a lot less nervous than most people would be. Most people would probably be pissing themselves by now. Was he pissing himself? Not yet. Although, wow, he could understand how someone might actually—

That sentence-interrupting final dash precedes the intrusion of the “real,” phenomenological world into Roosten’s consciousness. There’s much of James Thurber’s “Walter Mitty” in “Al Roosten”—and, indeed, much of Mitty in Saunders generally—perhaps because Saunders’s jangles lead him to explore the strange gaps between thought and action, reality and imagination. It’s worth sharing a few paragraphs of Saunders’s technique:

Frozen in the harsh spotlight, he looked so crazy and old and forlorn and yet residually arrogant that an intense discomfort settled on the room, a discomfort that, in a non-charity situation, might have led to shouted insults or thrown objects but in this case drew a kind of pity whoop from near the salad bar.

Roosten brightened and sent a relieved half wave in the direction of the whoop, and the awkwardness of this gesture—the way it inadvertently revealed how terrified he was—endeared him to the crowd that seconds before had been ready to mock him, and someone else pity-whooped, and Roosten smiled a big loopy grin, which caused a wave of mercy cheers.

Roosten was deaf to the charity in this. What a super level of whoops and cheers. He should do a flex. He would. He did. This caused an increase in the level of whoops and cheers, which, to his ear, were now at least equal in volume to Donfrey’s whoops/cheers. Plus Donfrey had been basically naked. Which meant that technically he’d beaten Donfrey, since Donfrey had needed to get naked just to manage a tie with him, Al Roosten. Ha ha, poor Donfrey! Running around in his skivvies to no avail.

We can note here the transitions between what the world sees (in those first two paragraphs) to how Roosten sees the world seeing him. This is Saunders at perhaps his finest, showcasing a meticulous control of free indirect style; Roosten is simultaneously pathetically endearing and loathsome. He is attractive and repellent precisely because we understand him—what it is to see him, but also what it is to be seen in the way he is being seen.

The titular story, which closes the collection, also offers a Walter Mittyish figure, a “pale boy with unfortunate Prince Valiant bangs and cublike mannerisms” who sneaks off into the woods to fantasize about the Lilliputian “Nethers” who might try to kidnap his crush Suzanne (whom he’s never addressed, of course). “Somewhere there is a man who likes to play and hug, Suzanne said,” the poor boy imagines. Again, this is Saundersville, where we laugh out loud and then reprimand ourselves for our cruelty and then engage, empathize, say, Hey kid, I’ve been there too…

“Tenth of December” is a sort of rewrite of two stories from Pastoralia, “The End of FIRPO in the World” and “The Falls.” I suppose I don’t mind, but I wish that Saunders’s jangles might lead him to new plots. Despite its rehashing of these earlier stories, “Tenth of December” delivers possibly the strongest case for empathy-as-transcendence in the collection. Our boy gets a shot at actually living up to his haircut—he’ll valiantly help a suicidal terminally ill man, who will, in turn, help him. What the story illustrates best though is how impulse precedes action and action precedes thought, how action can be shot through with memory:

He was on his way down before he knew he’d started. Kid in the pond, kid in the pond, ran repetitively through his head as he minced. Progress was tree to tree. Standing there panting, you got to know a tree well. This one had three knots: eye, eye, nose. This started out as one tree and became two.

Suddenly he was not purely the dying guy who woke nights in the med bed thinking, Make this not true make this not true, but again, partly, the guy who used to put bananas in the freezer, then crack them on the counter and pour chocolate over the broken chunks, the guy who’d once stood outside a classroom window in a rainstorm to see how Jodi was faring with that little red-headed shit who wouldn’t give her a chance at the book table, the guy who used to hand-paint birdfeeders in college and sell them on weekends in Boulder, wearing a jester hat and doing a little juggling routine he’d—

There’s that dash again. Dare I liken it to the dashes of Poe, of Dickinson? Maybe, maybe not.

I’ve shared some highlights of December, which I believe outweigh its weaker spots, unremarkable pieces like “Puppy,” a transparent exercise in how class in America inheres through a system of seeing/not-seeing others, or “Exhortation,” an amusing but forgettable memorandum that reads like Saunders-doing-Saunders.

“Home” is really the only story I would’ve left out of December. It’s the story of a war veteran trying to reintegrate into a society that flatly reiterates “Thank you for your service” while doing precisely nothing to actually thank the vet. Saunders’s sentiments are clearly in the right place, but the story rings false and hollow, its authorial anger overriding the humanity of its characters. At its worst moments, “Home” gives us a world of shuffling grotesques whose quirks preëmpt any possibility for genuine pathos. Saunders, usually in command of language, seems strained here. And it’s not a strain of venturing into new territory; no, all of Saunders’s tricks and traps are on display here (including an unexplained/unexplored substance called MiiVOXmax). Perhaps that’s the problem. Perhaps there’s too much of the author in the story.

And maybe that’s why I like the short, visceral two-paragraph perfection of “Sticks” so much–it seems freer, sharper. At fewer than four hundred words it’s easily the shortest piece in the collection (and the shortest thing I’ve read by Saunders). “Sticks” condenses the harried middle class hero of almost every Saunders tale into one ur-Dad, stunning, sad, majestic. It’s also the oldest story in the collection, originally published by Harper’s in 1995, which means it predates the publication of all his other collections. I don’t know why Saunders included it in December but I’m glad he did. It breaks up some of his rut.

That rut, by the way, is a pleasure to roll through—a fast, funny pleasure, but a pleasure nonetheless. Saunders is very good at highlighting our culture’s ugly absurdities, and he usually does so with moving pathos. And if his jangly sentences are their own raison d’être, then so be it. They are harmonious and sour, soaring and searing. Recommended.

[Ed. note—Biblioklept first ran this review in April of 2013]

Advertisements Share this: