Originally published on the Quietus.

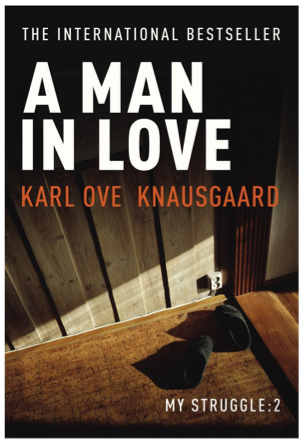

Early on in the second volume of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s blistering memoir Min Kamp (or, My Struggle – volume II of which is published in English as A Man in Love), following a passage in which he discusses what he calls the ‘drama of the soul’ present in Dostoevsky as well as the meaninglessness resulting from man’s subsequent division between conscious and subconscious, he writes:

Death makes life meaningless because everything we have striven for ceases when life does, and it makes life meaningful too, because its presence makes what little we have of it indispensable, every moment precious.

Last year the first volume of Norwegian literary sensation My Struggle by Karl Ove Knausgaard was published in English under the title A Death in the Family. The narrative focused on the death of his father, and the spectre of death permeated the book’s formless atonal style like a low hum – reverberating in the spaces between its minutely detailed description and brutally direct exposition.

The upcoming second volume tells of Knausgaard’s life after he leaves his first wife Tonje and his native Norway to move to Stockholm, where he reacquaints himself with Linda – a poet he met at a writing course years before. They fall in love and fatherhood soon follows; all the while Knausgaard is fighting writer’s block, attempting to write a second novel about angels (the material which was eventually to become A Time for Everything) and trying to cope with his constant desire for distance, not only from others, but from himself.

A Man in Love resounds with the same direct prosaic form as its predecessors: there are hugely detailed descriptions of seemingly banal occurrences in the author’s life – from changing nappies and children’s parties to cooking and shopping. Everything is presented on a flat narrative plane, only further accentuated by the book’s apparent lack of any tangible matrix to which the words can adhere. There is no event on the epiphanic scale of his father’s death to be found here, merely the routines of ordinary life: love, family, leisure and work. Paradoxes, like the one above, are everywhere throughout the book, they are continually undermined, diffused and withered away just as easily as they are formed; reflecting Knausgaard’s own struggle with his daily life and the struggle with writing itself in their destabilised recurrence. Meaning is consistently out of reach.

Ultimately, however, these factors and meandering frustrations only serve to fortify the strength of his approach. The continued extension of that vibrating hum, that face in the waves, which goes beyond what can be expressed in words, soon reveals itself to be something more than simply death – something which goes, again, beyond the feelings clustered around a single event, no matter how important.

This space between the words then – this lofty meaning to which it aspires – is something more than life, writing itself and even death. These abstract, sometimes incompatible, notions are not only linked together, but become seemingly interchangeable to Knausgaard. (‘And writing, what else was is it but death?’) But, in the end, not one of these concepts can sufficiently describe another. The continued juxtaposition of such weighty ideas, often collapsing in on themselves while simultaneously reinforcing previous relations, highlights not only the failure of writing but also of death (and of life) at being able to reach any “real” meaning. It is the exposure of this failure, in objects and relationships of the strongest kind, which make My Struggle one of the most remarkable works of literature in recent times.

It is, perhaps, no wonder that such a longing for distance seems to seep through every sentence: despite occasional beams of light which briefly turn the author’s face towards life, the birth of his first child, the look of his friend Christina when she thinks she is unobserved, or the most intense moments of love he feels for Linda – the search for something more surpasses and eclipses everything despite its evident futility:

the life around me was not meaningful. I always longed to be away from it, and always had done. So the life I led was not my own. I tried to make it mine, this was my struggle, because of course I wanted it, but I failed, the longing for something else undermined all my efforts.

The repeated failure, recalling Beckett’s ‘fail better’, keeps reinforcing the inescapable futility of the struggle; the impossibly close relationship between writing and life means that the novelistic project itself is doomed to fail. There are allusions to this later in the book when Knausgaard talks about his terrible memory, about the black holes which swallow up so much and leave memory a fragmented array of moments woven together with myth and fictions. Yet the book presents itself as one of the most detailed recollections of a life ever written, and so the failure of writing is not just in its ability to express that unreachable space of (and between) meaning, but also to accurately represent the struggle itself.

So, after life, writing and death have failed what is left?

The act of reading becomes a process of Heideggerian attunement where, beyond meaning and born out of the banality and anxiety, the confrontation with things as they actually are may occur. But any realisations that may arise in this state or mood are uncomfortable and unheimlich. The reverberations felt by the reader are the sour note being repeatedly plucked that Kertesz refers to in the remarkable Kaddish, For an Unborn Child where the author’s declarative ‘No!’ contains within it another impossible struggle. This discomfort from the realisation that meaning may never be found, even in the most intense moments of life, writing and even death, result in a turning back towards life. As one of Knausgaard’s favourite references Paul Celan wrote:

Don’t write yourself

in between worlds,

rise up against

multiple meanings,

trust the trail of tears

and learn to live.

My Struggle answers this call and rises up against multiple meanings in the most trenchant way possible. The panoply of details and the inexorable amalgamation throbbing beneath the veil like ‘the light behind the bookshelves’ results in the breakdown of semantics as well as the form of the novel as a whole and one encounters a space where the words themselves are the progenitors of their own collapse. Knausgaard’s writing creates an almost subatomic prosaic model which uses the formal constraints of speed and length (the entire work is three and a half thousand pages long and was written in just three years) to stretch the everyday to breaking point and cracks can be heard opening up between the molecular sentences.

Failure and failure alone may be ‘left as the sole fulfillable experience’, but in this incredible heterotopic work, amidst the withering paradoxes and the failure of escape the groundless ground of writing breaks open. In doing so it reveals something akin to music in the manner which Stendhal, defending it as the highest art form, described: something which does not depict or represent anything else but simply is.

Advertisements Share this: