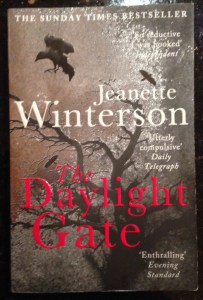

Starting from the assumption that Jacobean Lancashire was a rebel Catholic stronghold in a protestant country, Jeanette Winterson’s version of the most famous English witch trials is quite unlike any other. The Daylight Gate is a novella – not the hefty Victorian saga first told by Harrison Ainsworth – and it often strays away from the recorded historical facts. Indeed, this book examines witchcraft and Catholicism as “matters treasonable and diabolical” in an impressionistic, modernist manner, which culminates in a broody tale where events appear blurred by the mists of time.

Winterson takes a lot of poetic license with the facts as they are recorded in the trial documents, inventing new players, and placing famous people of that era in implausible situations. Her Alice Nutter – the central character she admits is not true to the actual historical figure – is lured into witchcraft, knows William Shakespeare and the magician John Dee, appears younger than the matron who was actually executed, and is bisexual. Yet at the same time Justice Roger Nowell, who led the puritanical crusade against the local cunning folk, gets painted in an unexpectedly sympathetic light.

However, Winterson’s rough characters and brutal situations are credible for that time, area, and circumstance. And she deftly strips away the romanticism found in some of the earlier novels based on these same events. I particularly admire her intelligent justification for the motives and causes behind the three remaining puzzles: Why was a gentlewoman of Mistress Nutter’s rank convicted alongside the common poor? Why did nine-year-old Jennet Device betray her entire family? And why did some of the accused willingly confess to diabolical crimes? Winterson has obviously considered these questions and reached her own conclusions about the excitement, hysteria, and sexual opportunities that open up during a witch hunt. And while she does not dwell on the misogynist drive that fuelled men like Nowell, she does address the other power imbalances associated with gender, wealth, and rank.

I appreciate Winterson’s sparse, poetic technique that functions like a series of flashbacks to a dangerous, incomprehensible era that was ripe with suspicion and superstition – a place where poor women did what was necessary to survive. Because they had no control over the real world they “must get what power they can in theirs,” though this is not a feel-good fairy tale where everyone lives happily ever after.

If you like intensity, and are open to magical realism, The Daylight Gate is an interesting introduction to the Pendle Witches. But it is ultimately more of a literary horror story than a traditional historical fiction.

Share this: