I’m trying to institute a new tradition in our house: on each of the children’s birthdays we will all get up and do birthday breakfast, open presents and be generally celebratory, and then I will go back to bed for at least an hour. I think it is a good idea for all of us to remember that this is the anniversary of these kids coming out of my body and that body could do with a little lie down.

I’m trying to institute a new tradition in our house: on each of the children’s birthdays we will all get up and do birthday breakfast, open presents and be generally celebratory, and then I will go back to bed for at least an hour. I think it is a good idea for all of us to remember that this is the anniversary of these kids coming out of my body and that body could do with a little lie down.

Stella’s birthday a few weeks ago was the first time I implemented this brilliant new tradition, and as I was lying down remembering her birth two years ago, I read an article by Chitra Ramaswarmy about her tendency to catastrophise. It was poignant to be reading about how incubating and then having children affects your outlook on life, particularly if one of your children is diagnosed with a disability.

Ramaswarmy experienced a very tough year in which numerous difficult things happened. By its end she had – after a complicated pregnancy – given birth to a healthy baby, her partner and mother had been seriously ill and recovered, and her son had been diagnosed with autism. Was it a year of disaster or, actually, was her family lucky?

Ramaswarmy describes how she is naturally a catastrophist, and inclined to be anxious about the potential for the worst case scenario to occur. She makes the case that the parenting is an antidote to catastrophising:

‘The hard graft and small, pure joys of looking after a baby and a little boy with autism anchor me to the present. The baby keeps me healthy, makes me feel lucky and gives me a constant dose of perspective. She is also exhausting: I am too tired and busy to catastrophise with as much fervour as the habit demands.’

This rings true for me. I am not a catastrophist. My natural tendency is towards slightly anxious optimism. But there is no doubt that I thrive when I am rooted in the present, and nothing keeps you in the present like having a small child, and then another, and then another. It’s not all rose-tinted snuggles – Sam’s early months were difficult for us all and he was frequently made miserable by reflux and feeding difficulties. But my focus on looking after him meant that by the time I looked up and around we had largely weathered the storm.

I went on to have two more babies and, luckily for all of us (and I mean luck, because these things are just a roll of the dice), Eli and Stella were babies that were easy to please. I have been largely too busy caring for all of them over the last eight years to spend much time thinking about what might have been, or what might go wrong.

What really resonated with me was Ramaswarmy’s reaction to her son’s autism diagnosis:

‘Then there is my brilliantly singular, loving and brave son. Before he was diagnosed with autism (that happened this year, too) I feared this moment: how will we manage? What will we do about school? How will he develop? Is everything going to be OK? The mystery and idiosyncrasy of autism can be frustrating, but it is also a visceral reminder that none of us knows what lies ahead and that compassion is the most powerful weapon against anxiety. So, here I am, living and thriving in the future over which I once catastrophised. And you know what? It is not so scary after all.’

We have had Sam’s birth described as a catastrophe, and in purely medical terms that may be true. But it has not been a catastrophe for our family. Sure there are difficult times, and complications, and we are sometimes sad and frustrated, but there is no catastrophe here. Something that was unfamiliar and therefore terrifying has become normal to us, and with familiarity comes an ease (hugely helped by the privilege of having carers to help and living in an adapted house).

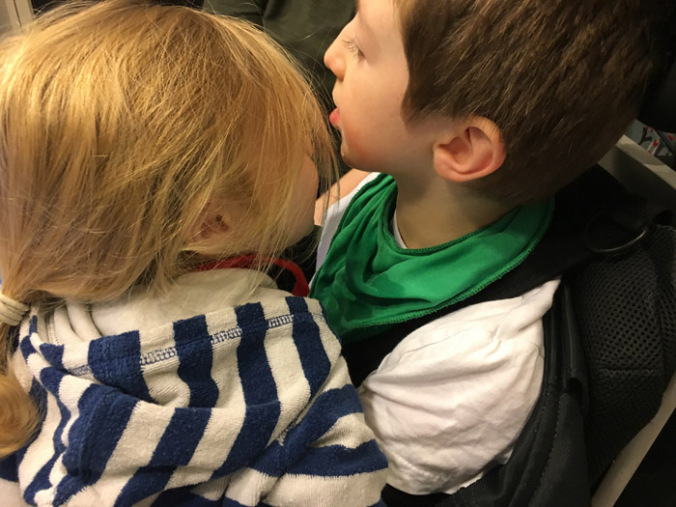

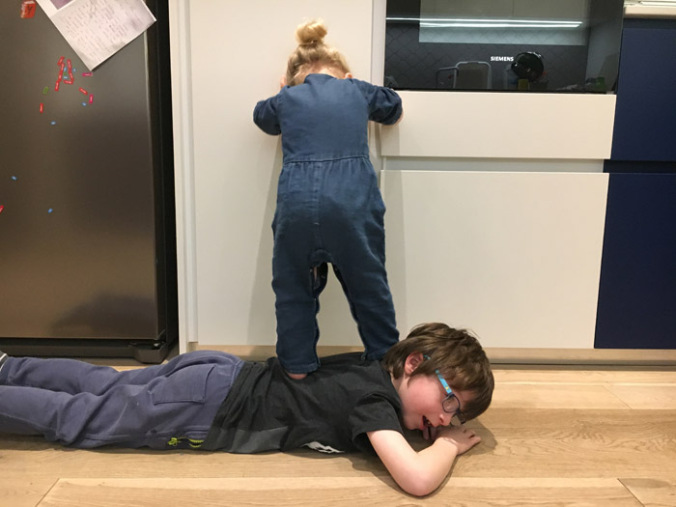

Over Christmas, all the kids were largely at home every day for two weeks, something that is rare, which meant they spent more time together than usual. Stella can now talk and asked about, or talked about, Sam at least every hour. Sam happily tolerated her climbing on his wheelchair, wiping his face, pressing her cheek into his. Eli is currently obsessed with gags about bodily functions and Sam encouraged him by laughing at his poo jokes. Sam let Eli play with all of his Christmas presents. Stella clambered on Eli and ruined his games and he only snapped after such goading that any jury would be on his side. Sam and Eli watched Star Wars for the first time and were scared and excited by the same bits. We went ice skating, for walks, swimming and to the cinema.

The ‘mystery and idiosyncrasy’ of cerebral palsy can be difficult, but it is also a prompt to live this life that is happening right now, even if it is one that would have counted as a bad outcome at some point. We have three healthy kids, and it’s not so scary after all. Are our family the survivors of a disaster, or are we lucky? Perhaps ask me again when they’re all teenagers, but on the basis of this Christmas we’re extraordinarily lucky.

- More