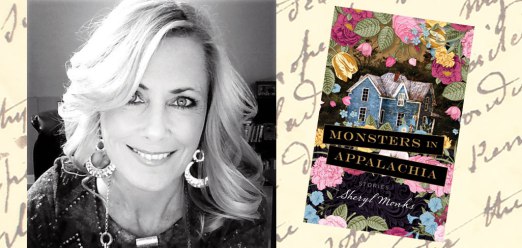

Monsters in Appalachia: Stories

By Sheryl Monks

Vandalia Press/West Virginia University Press

$16.99, 168 pages

As someone who has lived in California for all but two years of his life and feels a powerful attachment to this place — its weather, light, ocean, mountains, valleys, flora, and fauna – I am fascinated by writing that conveys the power of other places. I feel as though I know some of these locales so intimately, it’s almost as if I’d lived there. As a result, stories and novels with a sense of place so palpable that it’s almost a character remain indelibly etched in my mind.

After reading Sheryl Monks’ impressive debut collection, Monsters in Appalachia, I feel as though I have walked the mountains and valleys of West Virginia and North Carolina with her characters. The fifteen stories here are distinguished by a range of narrative voices that are as undiluted as a bottle of moonshine from the most hidden of hollers. Monks examines the lives of these hard-living and hard-learning people with an unrelenting, knowing stare that sees through the lies they tell each other and themselves.

Monks is concerned with good and evil as it plays out in the lives of the invisible people of Appalachia and similar economically struggling communities. Her stories are rich with biblical allusions from Exodus to Revelation. Desire and temptation are ever present, and salvation is just out of reach. It’s hot, humid, and dusty during the day and dark as coal at night. There is an almost claustrophobic intensity to most of these stories, whether the monsters are real or imagined. This is Southern Gothic storytelling at its finest.

In the opening “Burning Slag,” we meet a mother whose children have been taken away after she kills her abusive husband. She is so infuriated by the loss of her kids to a foster family in the area that she is driven to desperation again. “Robbing Pillars” is less than six pages long, but it’s more than enough to convey the lives – and deaths — of miners doing the dangerous work of pulling out pillars to collapse a nearly empty mine so they can mine the roofs. “That’s money standing there, supporting the roof, and the company wants every square inch.”

“Rasputin’s Remarkable Sleight of Hand” makes us a spectator at the county fair performance of an illusionist running a con that even the audience senses. But they, and we, can’t quite nail down what he’s doing or how. Is it possible he’s the real deal or the devil incarnate? Everything changes when a “fat girl with yellow eyes,” spellbound by Rasputin’s charisma, volunteers to participate in his act, and his show takes an unexpected turn that leaves us flabbergasted.

“Run, Little Girl” finds Brother Harpy, an elderly snake-handler, visiting the home of the minister of Lick Branch, whose wife is a sexy woman who has backslid six times. His young daughter is “his charismatic little angel, reaching into the burlap sack and drawing out copperheads and diamondbacks. Her child’s faith convinced the sinners of Lick Branch that God would protect any who sought Him. She had saved many souls.” She is fascinated with Brother Harpy and soon decides that she has her own powers that only he can appreciate.

“Merope” probes the conflicting impulses surrounding adolescent love and lust, with devastating results. “Crazy Checks” concerns two textile factory workers trying to figure out a way to game the system to qualify for disability payments, the “crazy checks” of the title. As in many of these stories, the unexpected can be counted on to do damage in a dozen different ways.

In “Justice Boys,” a mining strike has forced the men to find other ways to make money. “That’s what started things with the Justice boys. Arjay and Jimbo had been driving up and down hollers looking for pieces of scrap to sell to Luther Linny over in Mile Branch.” They trespass on the boys’ property, setting off a small-time gang war that climaxes on a night when the guys are gone and only Rita and the kids are at home.

According to those who know better than I, Monks accurately depicts the Appalachian dialect, attitudes, and beliefs, and she has created more than a dozen small worlds full of mesmerizing characters and startling conflicts. This is a dark and darkly humorous collection that heralds the arrival of a gifted “new” writer (Monks has been publishing stories for more than a dozen years).

Ron Rash has been the troubadour of the Appalachians for the past decade, but with Monsters in Appalachia, Sheryl Monks has joined him as a teller of twisted stories about a uniquely American place and culture.

Advertisements Share this: