Clipart Panda

Great Uncle Henry taught me to pluck Thanksgiving turkeys, and cousin Carol taught me to pluck my eyebrows. When my bowling instructor told me to quit thinking so much and “just let ‘er rip,” my average rose from forty to fifty; and my brother Bob showed me how to increase the pain of those I beat when playing rock, paper and scissors by licking my fingers before viciously slapping their wrists.

Having learned such important life skills from the best, when I began writing, I realized I should try practicing the techniques I’d learned from specialists around the world. Most people call them authors. I call them mentors.

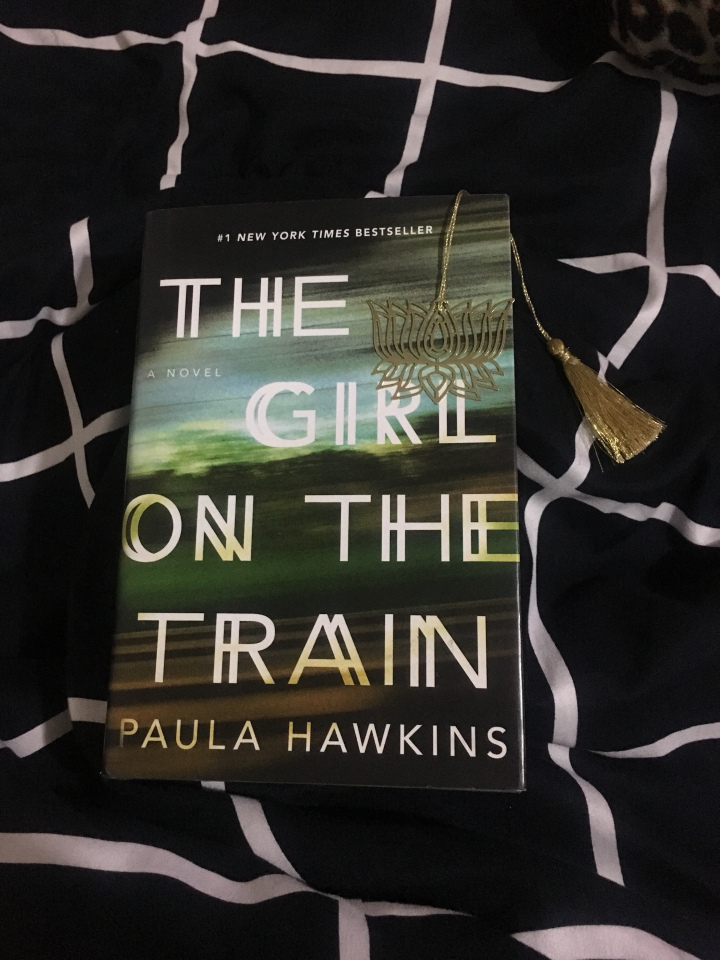

A.A. Milne’s “Winnie The Pooh” fascinated me as a child, and the words of Luis Alberto Urrea in “The Hummingbird’s Daughter” enthralled me last week. In between, a legion of authors enchanted me.

The authors of all those books became part of me, gave me a sense for paragraphs that pulse with rhythm, descriptions that usher readers into a scene and metaphors that surprise with their aptness. As I zipped through books in pursuit of compelling plots, I also developed an appreciation for dialogue that sounds real and for carefully edited works that give readers a sense of security. I was reading for pleasure, and, without realizing it, I was also learning from experts.

When I retired and began writing, my reading became more intent. Recently, though the plot of “The Hummingbird’s Daughter” captured me, I read Urrea’s words slowly, savoring his mastery over them as much as I enjoyed his rich story. I recorded delicious bits of his writing, studied them and thought how I could do something similar within my voice and topics.

Urrea, like all my must-read authors, treats words like crown jewels, selecting each with care. In “A Hummingbird’s Daughter,” he wrote, “Tomas rode his wicked black stallion through the frosting of starlight that turned his ranch blue and pale gray as if powdered sugar had blown off the sky and sifted over the mangos and mesquites;” and I felt I rode with him. I would probably have written, “Tomas rode his black horse across his ranch through starlight as white as frosting,” and few would have hopped on for the ride. But because I studied the rhythms and word choices of his sentence, I might write a stronger description the next time I write.

As another of my mentors, Mark Twain, said, “The difference between the right word and the almost right word is the difference between lightning and a lightning bug.”

I want to hurl lightening bolts like Twain and Urrea, but too often I propel tiddlywinks. For example, I know I overuse the tired twins, enjoy and like, but their alternatives rarely work. Value and appreciate are too refined, and the phrase, take pleasure in, seems a bit uppity. Casual use diminishes the compelling emotion of love. Treasure strikes me as over the top, and relish makes me think of hotdogs.

So yesterday, when I started “Dancing at the Rascal Fair” by the western writer Ivan Dog, I decided to watch for his use, or not, of like and enjoy. Does he sprinkle them liberally in his prose? Or does he have other techniques for describing or distinguishing the emotions they represent?

I’d like to discover his approach to my dilemma. In fact, I’d enjoy it.

Advertisements Share this: