Fascinated with the form of the tripot, and interested to see what was involved in making one, I have started my own. I couldn’t think of a better way to understand and appreciate it than to make one myself.

Loosely following an article in Woodwork by Hugh McKay on his process of making a pentapot (five vessels in one), I began work on my own.

First, I played around with a sheet of paper and a compass to lay out the overall sizes of the three vessels for my tripot. I wanted their diameters to be significantly different for interest. Since most of the shaping is done on the lathe, I knew that I needed the other two pots to clear the lathe bed when any one was mounted on centres. That limited the overall size of the piece I could make. I figured that it was also important that the three pots meet in the middle, and for the walls to not overlap so much that, when hollowing them out, the cavities would meet.

Once I had a layout that met my criteria, I transferred it to a piece of 1/4” MDF which became my template. I’m not sure this was really necessary, but it was one of the steps McKay used in the creation of his pots (the template did help me when I needed to start again… more on that later).

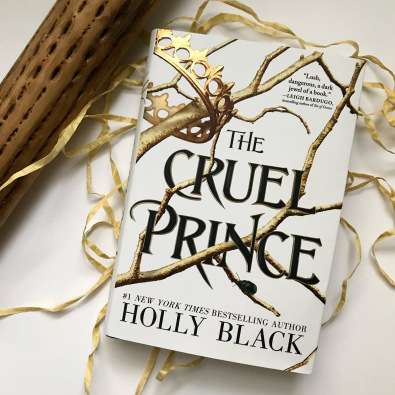

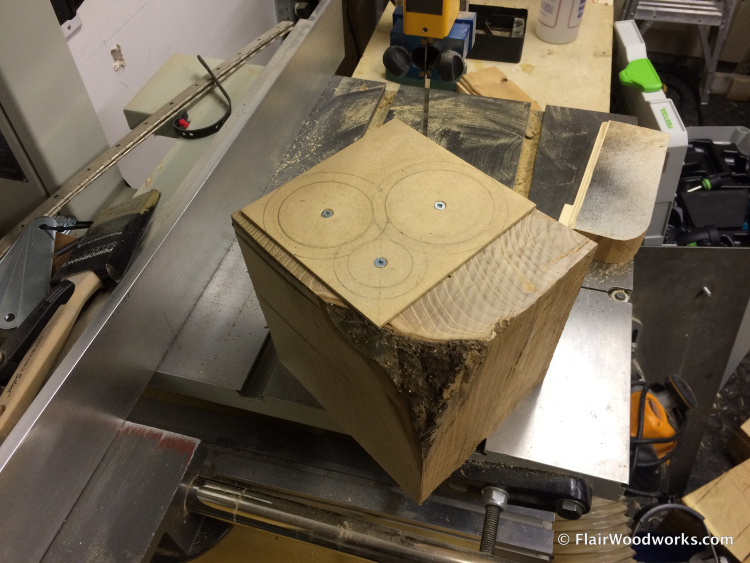

I chose a chunk of black locust about 8” thick.At the bandsaw, I squared up the blank, ensuring both ends were parallel to each other. I carefully positioned my template on the end grain, avoiding any checks, bark, or knots that could have compromised the strength of the tripot. With a short screw in the centre of each circle representing a pot, I fastened the template to the black locust. Carefully, I cut to the lines using my bandsaw.

Next, I determined how tall to make each pot. I had to remember to accommodate for some chucking wastage at one end, where the screws would go in to hold the face plate. Again, following the recommendation of McKay, I used a drill press and forstner bit to remove the bulk of the waste. Boring into the end grain of a hard wood was not quick, and the results were not especially clean, with stalagmites and brad point divots abound. I quickly cleaned up the resulting surface with a hand saw and chisels.

To profile the exterior, the pot could not simply spun on the lathe and a gouge be presented to the work unless you were impossibly good at quickly applying and removing the tool as the other two vessels off-axis came around. Instead, shaping is done with a router with the lathe unplugged. This required some jigging.

I created a plywood platform that got mounted to the lathe bed. For my smallest router, which I had chosen to use for the shaping, I built a cradle to hold it securely in line with the lathe’s axis when resting on the platform. Lastly, I cut a template for the router to follow.

For a clean cut, ease of control, and long reach, I chose to mount a 1/4” up-spiral solid carbide router bit in the trim router. With a pot screwed to a faceplate and mounted on the lathe, I used the router to estimate where to position the template to remove the minimum amount of material, while creating a fully shaped vessel without flat spots. I clamped the template with a pair of clamps and got ready to start routing.

My left hand was on the wheel controlling the rotation of the lathe, and my right hand moved the router on the platform. Taking shallow bites, I slowly worked my way around the pot as far as I could. It took patience and focus to take only small bites, and to keep the router firmly on the platform. Several times, the router caught, tipped forward, and ended up carving deep holes in the side of the pot, requiring me to re-adjust the template to remove the divots. In the end, I ended up deciding that there was not going to be enough material left to make it worth continuing.

I started again. This is where that template came in handy. I simply screwed it to a new piece of locust and cut it out again at the bandsaw. After determining the height of the pots, I cut across the tops of the pots with a coarse handsaw, then split away the waste with a chisel and mallet. This was much quicker and cleaner than using a forstner bit.

At the lathe, I took the shaping process much more cautiously. Analyzing my previous failure, I realized that I would have a better chance of success if I: clamped the router to the platform to avoid tipping; didn’t use a spiral bit to prevent the bit from wanting to pull itself into the work; used a router bit with a short cutting length and a bearing to keep the cutting part from engaging with the other two vessels; and screwed the template securely to the platform. I took all these precautions for the second attempt.

In this video, I describe my setup, and demonstrate the shaping method.

My process worked well, and the extra precautions I took were worth the effort.

After routing all three pots as much as I could, there were a few spots that the router couldn’t access. I cleaned those up with skew chisels and carving gouges.

Next up: hollowing!

Share this via: