There have been many discoveries of potentially habitable planets orbiting stars other than our own over the last few years. Now things are getting even more exciting. Scientists have documented a star surrounded by seven Earth-like planets – several of which would be at the right temperature for liquid water, and potentially life, to exist.

But is it possible to know anything about what these planets are like beyond simple measures such as temperature and mass? There may indeed be several factors that can give us a clue – let’s take a look at what planetary processes we might expect to find there.

The seven planets orbit an ‘ultracool dwarf‘ a mere 39 light years away. However, with a mass of only 8% of our sun’s and shining less than 0.1% as brightly, it is at the small, faint end of the ‘red dwarf‘ star type, barely able to power itself by nuclear fusion.

Telling transitsIn 2010, a group of scientists began monitoring the closest dwarf stars using a robotic telescope in Chile called TRAPPIST (the Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope). They were hoping to find periodic dips in brightness caused by a planet passing in front of the star, cutting out part of its light (a transit). In 2016, they found their first candidate: an ultracool dwarf.

They named this star TRAPPIST-1 and began to study it with more powerful telescopes, including NASA’s Spitzer space telescope. This revealed a total of seven transiting exoplanets there.

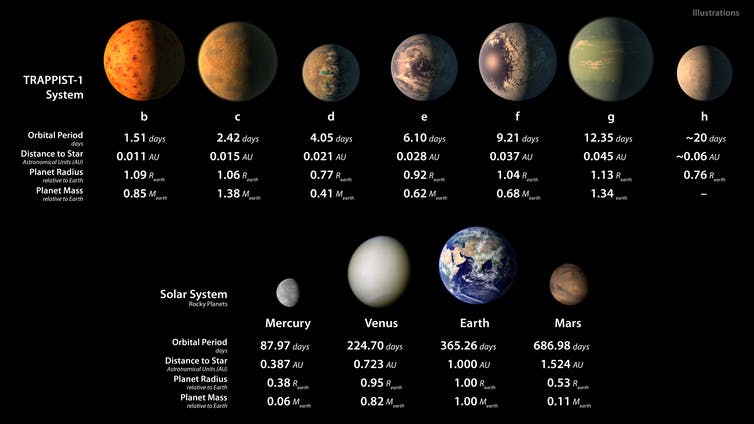

- The amount of light blocked out by each exoplanet during a transit reveals its size

- The repeat frequency reveals each exoplanet’s orbit time

- From this, the laws of gravity allow us to work out its distance from the star.

Amazingly, the planets of TRAPPIST-1 span only a narrow range of sizes, not much different to Earth, and are all much closer to their star than Earth is to the sun. However, TRAPPIST-1 is so faint that even its innermost planet may be just cool enough for liquid water to exist on its surface, while its outermost planet may be just warm enough to avoid global freezing.

This artist’s conception shows what the seven planets of TRAPPIST-1 may look like, based on available data about their sizes, masses and distances from the star. NASA/JPL-Caltech

This artist’s conception shows what the seven planets of TRAPPIST-1 may look like, based on available data about their sizes, masses and distances from the star. NASA/JPL-Caltech

The slight irregularities in transit times can be attributed to neighbouring exoplanets influencing each others’ orbits. This suggest that most of the family are Earth-like in their density and not just their size. There is no way to be sure yet how much water most of them have, if any. Similarly, it’s hard to know whether any resemblance to Earth extends as far as having plate tectonics and a distinction between oceanic and continental crust like Earth.

Seeds of life?With most or maybe all of its seven known planets in the not-too-hot, not-too-cold ‘Goldilocks zone‘ around the star, TRAPPIST-1 offers the intriguing prospect of several Earth-like planets capable of hosting Earth-like life around the same star.

TRAPPIST-1 is as young as ultracool dwarfs go, maybe only half a billion years old. Thanks to the frugal rate at which it uses its nuclear fuel it has a further 10 trillion years left to run (a thousand times longer than the sun). On Earth, it took two billion years to go from microbes to multi-cellular organisms and another billion years for intelligence to emerge. So while we may not expect advanced civilisations to exist on the TRAPPIST-1 planets, some simple lifeforms may be in the works or already exist.

TRAPPIST-1 and its planets are sure to be among the prime targets for the James Webb Space Telescope, likely to begin operations in 2019. This should be able to detect the presence of any atmosphere about a planet whilst it is in transit across the star and maybe even reveal whether atmospheric composition seems to have been modified by living processes. Until then however, all we can do is wait…

Advertisements Share this: