Read 17/07/2017-20/07/2017

Rating: 4 stars

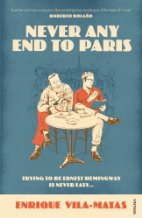

Read for the Reader’s Room Read Around the World Challenge: Spain

The Enrique Vila-Matas of Never Any End to Paris, who both is and isn’t the novelist Enrique Vila-Matas, is convinced that he grows to resemble Ernest Hemingway more every day. Nobody else agrees with him, least of all his wife, most of all the organisers of a Hemingway Lookalike contest in Key West. Like the novelist, the book’s Vila-Matas has been obsessed with Hemingway since he read A Moveable Feast as a teenager. In his 20s, he moved to Paris to try to absorb some of what inspired Hemingway. Never Any End to Paris is Vila-Matas looking back on those youthful days.

I’m not the biggest fan of Hemingway, but I own two copies of A Moveable Feast: the original version published after Hemingway’s death, based on his draft and notes, and the revised version edited by his grandson. I read the original version years ago, but I can only call up vague memories of F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald and Shakespeare and Company. I need to re-read it. Perhaps I should have done so before starting Vila-Matas’s humorous tribute to it.

The format of Never Any End to Paris is that of a lecture, broken down into sections for delivery to an audience. Each section is numbered like a chapter, and most sections are around a page long. It lends a particular rhythm to the story. The structure also put me in mind of Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet because of the slightly disjointed way Vila-Matas jumps from topic to topic. I paused my reading of Pessoa because his disjointedness became too much. Fortunately, Vila-Matas is humorously self-aware, so the disjointedness was less of an issue. I enjoyed his breezy way of recalling episodes in his youth and his more recent past. He is quite the raconteur.

He also doesn’t write like Hemingway. He writes more like Borges, whose work he first discovered while living in Paris. There is subtext to his writing, which is unpicked by reading it with a sense of the irony Vila-Matas refers to in his lecture. He seems to be searching for truth, not in facts or the reality of life, but in the margins of life, or the mirages that what we think of as reality is often made up of. He has a delightful sense of the absurd, particularly the absurdity of his younger self.

While first living in Paris, the young Vila-Matas decides to be a Situationist. He candidly admits that he wasn’t actually a Situationist, but rather thought he had the air of a Situationist. He dressed entirely in black, bought a pipe like Sartre’s and some glasses, and spent his days sitting in cafés, pretending to smoke at the same time as pretending to read French poets. He was every romantically inclined twenty-something who equated despair with being interesting. In short, he was a Morrissey lyric.

Looking back on this time, Vila-Matas realises how absurd he must have seemed to other people. Aren’t we all absurd in our twenties, though? Trying to work out who we are, what will become our enduring adult self, holding dreams and ideals as though our authenticity depends on it.

In those days, I started walking around the neighbourhood streets believing myself to be an interesting person. Sometimes I sat on the terrace of the Café Flore or Chez Tonton and tried to get passers-by to notice me, to observe me, with my Sartresque pipe, reading with the air of a young, dangerous French poet. Sometimes – I was well practiced – I looked up from the book I was pretending to read and at that moment my penetrating maudit-writer look was at its most piercing.

Maturity also gives him a greater perspective on his first steps as a writer. He says he knew nothing. He had read very little. He expected the experience of living in Paris would feed his imagination in the way it had fed Hemingway’s. He sought advice from other writers in his social circle, but lacked the literary vocabulary to understand what they told him. Eventually, as a result of trying LSD for the first time, he decided that his inspiration should come from the resultant widening of his visual field of perception. This leads to his rejection of realism in literature. He is quite dismissive of realist writers.

Certainly an author who has come to the experience of writing after having imbibed the contents of the family library seems much more respectable than one who has begun to construct his literary edifice after an acid trip. The quality of my early poetics seems scanty if, as I am saying, it was basically sustained by a drug that simply widened my visual field of perception. And yet, I’m not sure now that I should reproach myself at all, rather quite the reverse. Because while it’s true that later on I read quite a lot and my literary knowledge was strengthened, it’s also true that LSD, by opening up my visual field, was not at the time by any means an insignificant source of inspiration. Besides, some of those perceptions of a distinct reality have lasted firmly and still today carry a highly remarkable energy, and are the reason I can laugh at realist writers, for example, who duplicate reality and so impoverish it.

This passage went a good way towards explaining Vila-Matas as a writer to me. I’ve never read anything by him before and didn’t know what to expect. I’m glad that I read this novel first, because I’m sure that understanding his approach to writing – his delighting in irony, his use of parody, his playfulness with paradox – will make future readings of his works more satisfying.

The things I enjoyed most about the book were the wry humour and the little gems of wisdom scattered among the occasionally disastrous experiences that Vila-Matas gathers during his Paris sojourn. It’s very funny in the way the author acknowledges how seriously he took himself and needed to be taken by others, at the same time as he laughs at his own absurdity. And for all that the Vila-Matas of the novel claims to have been poor and unhappy in Paris, this faux-memoir is a hymn to Paris’s charms. Vila-Matas visits every café that Hemingway frequented and, much as Hemingway was among famous contemporaries and had famous mentors when he first lived in Paris, Vila-Matas is surrounded by a mix of established auteurs, members of the nouvelle vague, and Spanish and Latin American contemporaries. It is rich company for him to feel mediocre and out of his depth in, as he attempts to triumph.

Advertisements Share this: