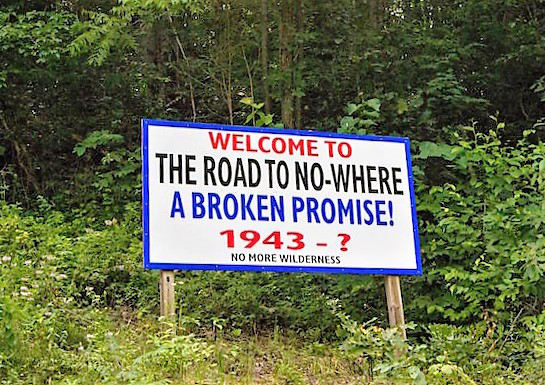

A seven-mile stretch of road from the southern lip of Great Smoky Mountain National Park to its tunnel terminus remains a source of irritation for generations of locals, and a symbol of an unfulfilled promise from the Federal bureaucracy,

which once pledged to replace submerged Highway 288, but lost their way amid a forest of red tape and environmental concerns.

Fontana Dam begat Fontana Lake in 1941 after the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA)–in concert with the Army Corps of Engineers–built a hydroelectric plant for ALCOA in consideration of the military’s demand for aluminum essential for aircraft, ship-building, and munitions during WWII. Consequently, communities and roads disappeared under the high-water reserves, and townspeople lost their land and their livelihoods.

In exchange for losing Highway 288, the displaced people of Swain County were promised a road north of Fontana Lake–through Great Smoky Mountain park lands–for continuing access to their ancestral cemeteries left behind, and compensation for relocation assistance. However, most of the 1,300 citizens who resisted the move never saw a dime after ultimately fleeing the rising waters.

Thirty years later, after building 7.2 miles of road and a quarter-mile tunnel, appropriated funds had dried up and the project stalled. By 2003, the National Park Service eventually revealed a feasibility study listing several considerations for public debate, and in 2007, issued a 13-page report detailing the government’s position, electing the No-Action Alternative:

The No-Action Alternative would forego any improvements to Lake View Road with the exception of routine maintenance. Under this alternative, there would be no changes to the existing conditions within the study area. No compensation would be provided in lieu of building the road. NPS would continue to provide transportation across Fontana Lake for annual cemetery visits and would maintain current amenities, policies, and practices of GSMNP.

Subsequently, Swain County sought a monetary settlement, demanding $52 million from the Department of Interior for defaulting on the original agreement. Yet to date, only $12 million has been paid, thus generating a pending lawsuit for the balance of money owed.

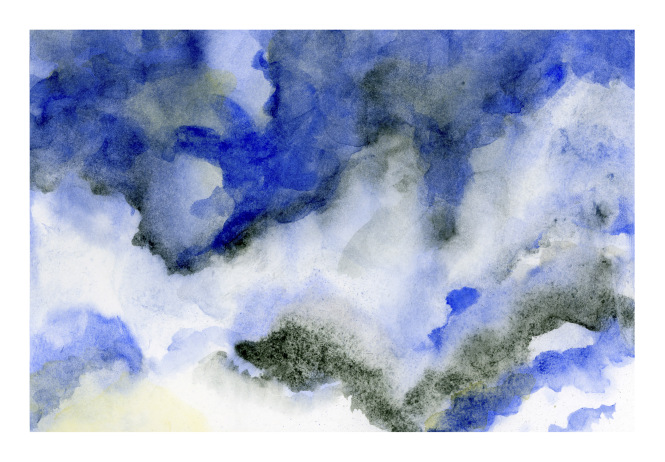

After learning about the history, Leah and I decided to make the pilgrimage to see this road for ourselves. We departed Bryson City on a dreary autumn morning, surrounded by mist and brisk winds that had us zipping up and foraging for hats and gloves from a backseat storage bin.

The drive along Fontana Road took us through bucolic farms and pastoral settings.

We followed the lightly traveled road until we reached the park entrance, and continued along a windy incline dotted with shrouded overlooks of the Tuckasegee River below us.

We knew we had reached the end of the line when we crossed over Nolands Creek,

and encountered a barricade of steel poles that barred us from approaching the tunnel around the bend.

The ¼-mile tunnel was dark and dank. And while a flashlight was a handy accessory for navigating the rutted road and avoiding scattered animal feces,

it became an essential tool for spotlighting the pervasive high school graffiti that randomly “decorated” the oft-covered whitewashed walls–

–most of it, a reflection of egocentric teenagers flexing their hormones…

…but in other cases, the graffiti represented a cathartic release of current political expression–

–bringing new meaning to an erstwhile patch of pavement.

As advertised, the “Road to Nowhere” terminated on the back side of the tunnel,

casting a glimpse of an uncertain future fraught with empty promises disguised as good intentions.

Share this:

- More