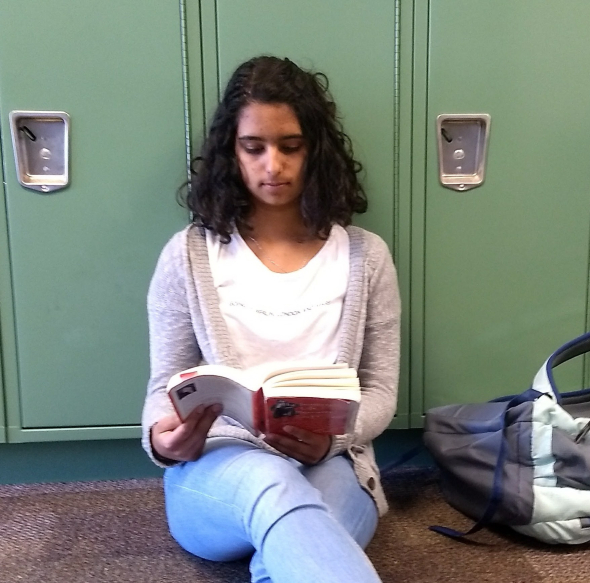

Advanced Placement Language and Composition (AP Lang) students have just concluded their study of the nonfiction book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks written by Rebecca Skloot. Skloot’s book details the historic events that led to the discovery of the first immortalized human cell line known as HeLa. Most importantly, the book is about the story of Henrietta Lacks, the woman behind the cells. Skloot’s took many years to learn and write about the life of Henrietta Lacks.

Advanced Placement Language and Composition (AP Lang) students have just concluded their study of the nonfiction book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks written by Rebecca Skloot. Skloot’s book details the historic events that led to the discovery of the first immortalized human cell line known as HeLa. Most importantly, the book is about the story of Henrietta Lacks, the woman behind the cells. Skloot’s took many years to learn and write about the life of Henrietta Lacks.

“The book is important because we had no awareness of the life of the woman behind the HeLa cells,” said Leslie Bragg, AP Language and Composition teacher. “I’m so impressed with Skloot’s commitment to learning her story and breaking down the barriers of trust with the family and having a relationship with them in order to tell that story.”

Henrietta Lacks was a poor, African-American woman living in Baltimore, Maryland in the 1950s. Lacks had been diagnosed with cervical cancer and was being treated at John Hopkins hospital.

“There were times when I don’t think she was heard,” Bragg said. “And the [time] that comes to mind most vividly is when she went back and told [the doctors] the cancer was still there and they continued to send her away.”

It was at John Hopkins where a sample of her cancer cells was taken from her without her consent. While unethical, this practice was actually legal and common at the time. When the cells were taken, they were expected to die soon afterwards. However, the research assistants working under cell biologist George Guy found that the cells not only didn’t die, but they had multiplied to the size of the container in which they were being held. The first immortalized human cell line, HeLa, was discovered.

Guy’s researchers split the cells into other containers and found the same thing the next day. Unlike normal cells, the cancerous HeLa cells lost the ability to stop reproducing. HeLa grew rapidly and soon scientists all over the world were having HeLa samples shipped to them. Since HeLa cells replicated ceaselessly, scientists could use HeLa to facilitate medical discoveries surrounding cancer research like the polio vaccine and how the parvo virus infects human cells.

While scientists, and later the public, found out about the immortal cells, Henrietta’s name was lost and the cells became known as simply HeLa. Some reporters started speculating the source of the cells and began attaching names, like Helen Lakes, to the cell line, but, unfortunately, they got the name wrong. The cells lived long after Henrietta Lacks died from cervical cancer despite the doctors’ attempts to cure it.

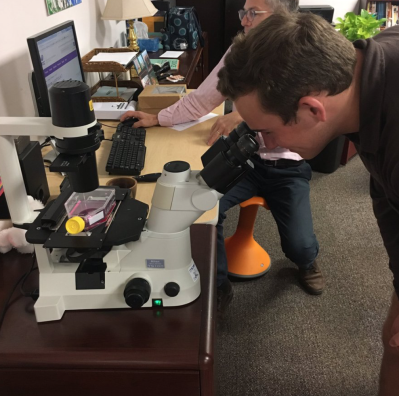

On October 10, Dave Wessner, a biology professor at Davidson College, visited all four AP Language and Composition classes to provide an inside look at how scientists work with immortalized cells.

Wessner shared that cells have many special needs in order to stay alive, they have to stay in an incubator that is kept at 37 degrees C with a high Co2 concentration. In order for the Co2 levels to stay at a consistent state, the scientists pump Co2 into the incubators. The cells also like to live in a specific PH and are kept in a fluid made with PH indicator, fluid with nutrition, glucose and salt, for easy maintenance. While HeLa cells, or any other immortalized cells, are alive, scientists can infect them with diseases to test out vaccines without having to inject them in a living human.

Wessner shared that cells have many special needs in order to stay alive, they have to stay in an incubator that is kept at 37 degrees C with a high Co2 concentration. In order for the Co2 levels to stay at a consistent state, the scientists pump Co2 into the incubators. The cells also like to live in a specific PH and are kept in a fluid made with PH indicator, fluid with nutrition, glucose and salt, for easy maintenance. While HeLa cells, or any other immortalized cells, are alive, scientists can infect them with diseases to test out vaccines without having to inject them in a living human.

Even though scientists have access to a lot of cells, cells don’t all do the same things. There are epithelial cells from the cervix which form sheets of epithelium that cover and line organs as well as produce and secrete mucus. Then there are stem cells have the ability to develop into specialized cells for specific organs. Because of the different types of cells, there could be different ways that the cells could react in different experiments and, therefore, different results. The appearance of HeLa cells caused there to be many scientific discoveries that would not have materialized if the medical community did not have Henrietta Lacks’s cells.

“I think that [The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks] accomplishes so much of what we value,” Bragg said about including Skloot’s book into her curriculum. “It’s so beautifully written but the research component [and history] of it is so fascinating.”

Share this:

![Closer to You (Haven, Montana Book 1) by [Sanders, Jill]](/ai/082/677/82677.jpg)