OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

The Spring 2017 issue of Catfish Alley is now available! And, as usual, I submitted an article on a local plant that I like to use as medicine. As you can already tell by now, the article was on poke or Phytolacca americana.

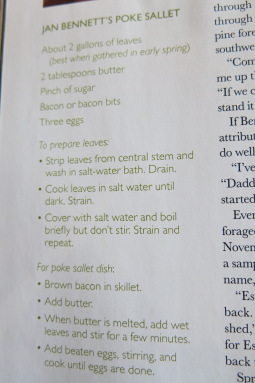

A fun twist this quarter, is that my article on poke was preceded by an article on Jan Bennett, the local “poke sallet queen” (her recipe is above). The other text image above is a line from the song “Polk Salad Annie” by Tony Joe White.

Another interesting thing is that, after the magazine was published, I got an email from someone local saying that he actually harvested poke greens for the last poke green canning facility in the US, The Allens, in Arkansas. He said he was helping hid dad make some extra money at the local canning facility.

I’ve posted the unedited story that was published in Catfish Alley below (although, I do like their tight, edited version better).

With spring well on its way, we have to talk about the semitropical plant, pokeweed or poke (Phytolacca americana). You can find this native plant growing from the Deep South all the way up to the Midwest. It even has relatives in South America, East Asia, and New Zealand. It is easily found along roadsides, forest edges, disturbed areas, and fields.

To some farmers it’s a pernicious weed. To native plant enthusiasts, it’s a spectacular addition to native plant landscaping. Its white blooms adorn the plant from early summer to fall while the showy pink stalk adds color and texture to any yard or garden. The dark purple, pea-size berries hang from clusters in the fall. The plant dies back every year and will eventually grow up to 4-6 ft. And, if you want to attract birds to your yard, the gray catbird, mockingbird, cardinal, and brown thrasher, and cedar waxwing all frequent this plant for its fall berries.

Dyed yarn using poke berries, by Grackle & Sun

To a craftsperson that uses natural pigments to dye fabric and yarn, poke is well-known. Depending on the mordant (or fixative), you can render different shades of fuchsias, salmony-brown colors, periwinkle purples, and even red. Actually, the word “poke” even alludes to its traditional use as a dye. It comes from the Virginia Algonquian (Indian) word “pakon” or “pucone.” Pakon refers to a plant used for dye or staining, and pokeweed’s berries have been used as a dye for centuries.

To a historian, poke would also be of interest. In the botanical world, there are well-founded rumors that Thomas Jefferson used poke berry ink to write the original US Constitution (on hemp paper). During the US Civil War, many of the letters written by soldiers to their families back home were written in poke berry ink as well.

Of course, you know that my column in this magazine is always about plant medicine and herbs. You may have heard that this plant is dangerous and toxic. So, why would I be writing about it as medicine? Well, it is and it isn’t toxic. Although this plant is one that I would use a high level of caution with, it still has a lot to share with us. After all, dosage has a lot to do with the toxicity of a plant.

For now, let’s look at its use as a food. Some of my readers may know about “poke sallet,” as it is an old tradition here in the Deep South. When times were lean and the early settlers were living off the land, poke sallet was a survival food. Considering that it was the first greens to appear after winter-time, it was an early spring tradition to eat poke sallet in the Deep South and Appalachia.

Young poke leaves, by Tinycamper

Basically, they would harvest the young, spring leaves (typically leaves that are under six inches long) of the poke plant and then boil them three times, draining the water and refilling it with fresh water each time. This leeching process ridded the plant of its toxicity. The boiled leaves were then eaten to move the lymphatic system and clean out the blood.

Let’s go back and think about life at that time. Settlers lived close to the land and had some sensibilities when it came to seasonal living. Their survival depended on their awareness of these things and the practicality in which they approached it.

As one of my teachers, Phyllis Light, has explained to me, one awareness piece of Southern Folk medicine is that the blood gets thicker and moves to the core of the body in the winter-time, just like a tree’s sap. During these winter months, people ate heavier foods, lived a more sedentary life because it was cold, and put on some winter pounds. Poke sallet was eaten in the spring to counter winter stagnation by moving the lymph fluid and breaking up residual fats in the lymph.

Poke sallet makes a lot of sense when you think of it in those terms. However, I have never made the “sallet” myself, so I can’t speak from experience.

This brings me to talking about poke’s medicinal properties. Even though I am going to share this information with you, I urge you to only use poke as a medicine if guided or supervised by a trained herbalist or Clinical Herbalist. There are issues of poisoning with this plant. Namely, children seeing those beautiful dark purple berries, and, thinking that they are blueberries, eating a whole mess of them only to have their stomachs pumped later. As I said, use caution.

Let’s start with the berries then. As I mentioned earlier, a variety of birds eat the berries with no issue of toxicity. That’s because the seeds’ outer coverings are rather hard and the birds do not digest them at all. This allows the seeds to pass through their systems and disperse freely as droppings.

The legendary Southern Folk Herbalist from northern Alabama, Tommie Bass, would eat a few berries every day for six days in the fall to clean the blood and move the lymph. I have actually done this practice myself, except eating one berry a day for three days. The important thing is to not chew the seeds and simply mash the berry against the roof of your mouth and swallow. To learn more about the life of Tommie Bass, I urge you to go to folkstreams.net and watch “Tommie Bass: A Life in the Ridge and Valley Country.”

Tommie Bass, photo by Tom Rankin (actually my former photography professor at Univ of MS)

Then there is the root, the most potent part of the plant, and the most toxic. Many herbalists chose not to use this herb while others feel very confident and comfortable. Either way, it is a low dose herb, meaning the dose (in tincture form) is 1-5 drops, depending on the person. The root can also be used topically as an infused oil or a salve (the root is infused in oil and then thickened with beeswax).

I, personally, love digging up poke root and cutting it open. It has a strangely sweet smell that is fragrant and earthy. There are rings in the root like rings on a tree, showing each year of growth. And, the color of the root flesh is a really pale yellow-cream.

Traditionally, the root has been used to move the lymph fluid through the lymph vessels, to encourage lymphatic function, to clean the blood, for its anti-viral properties, to eliminate swollen lymph nodes, and as a stimulant to the immune system. Topically, it can also be used for mastitis, for common warts, and for swollen glands around the thyroid associated with hypothyroidism. I also find it to be a great topical salve to use on the throat for strep throat. When combined with anti-microbial herbs such as propolis and immune-stimulating herbs such as southern prickly ash, I find it to be the right defense for most viruses and bacteria that can attack the system.

Truly, poke is a powerful herb that deserves a lot of attention as well as a lot of precaution. When used appropriately this herb can give a person needed support and relief from a health imbalance. Like many of our plants, the right knowledge will lead to proper and effective use. For now, let’s just enjoy the unusual beauty of poke and deepen our interest on its purpose in our life and in our environment.

Poke article spread in Catfish Alley

Advertisements Share this:

![Pageflex Persona [document: PRS0000030_00040]](/ai/048/232/48232.jpg)