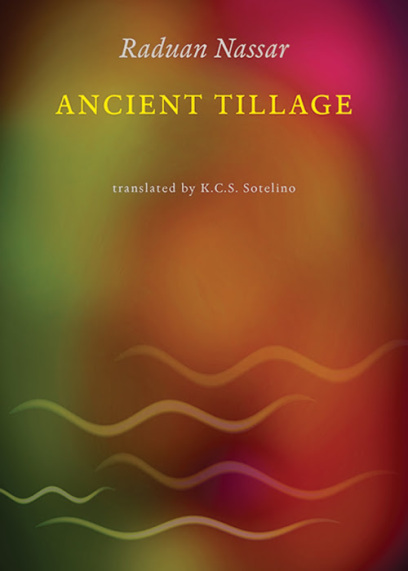

On January 31st, 2017 New Directions Publishing is bringing this masterpiece, published originally in Brazil in 1984, to an English-reading audience for the first time:

On January 31st, 2017 New Directions Publishing is bringing this masterpiece, published originally in Brazil in 1984, to an English-reading audience for the first time:

For André, a young man growing up on a farm in Brazil, life consists of “the earth, the wheat, the bread, our table, and our family.” He loves the land, fears his austere, pious father, who preaches from the head of the table as if from a pulpit, and loathes himself as he begins to harbor shameful feelings for his sister Ana. Lyrical and sensual, written with biblical intensity, this classic Brazilian coming-of-age novel follows André’s tormented path. He falls into the comforting embrace of liquor as—in his psychological and sexual awakening—he must choose between body and soul, obligation and freedom.

I was completing a degree in literature the year this was first published, but Portuguese was not an option for my reading, nor was Brazil really on my map at that time. As a result, or for whatever other reasons, I never heard of this book before.

Work assignments took me to Brazil several times in the intervening decades, and Latin America has been home base for most of the last two decades. I know I must read this, and soon, so it has just moved to the top of my next-book list. But for a very different reason the author has my attention, thanks to this:

WHY BRAZIL’S GREATEST WRITER STOPPED WRITING In 1984, at the height of his literary fame, Raduan Nassar announced his retirement, to become a farmer.By Alejandro Chacoff

Back to the land is a theme of a large number of posts on this platform, including those that we link to from external sources and some of a more personal nature–hundreds of posts on the variation of discovery that comes with connecting to agricultural roots, whether old fashioned or newfangled. Mr. Nassar’s story is one variety I appreciate for its sign of audacious humility, a combination of words I am particularly keen on at the moment.

Raduan Nassar was forty-eight and at the height of his literary fame when, in 1984, he announced his retirement. He wanted to become a farmer. ILLUSTRATION BY BEN KIRCHNER

In 1973, the Brazilian writer Raduan Nassar quit his job. After six years as editor-in-chief at the Jornal do Bairro, an influential left-wing newspaper that opposed Brazil’s military regime, he had reached an impasse with one of the co-founders, who was also his older brother. The paper had until then been distributed for free, and the brothers couldn’t agree on whether to charge subscribers. Nassar, then thirty-seven, left the paper, and spent a year in his São Paulo apartment, working twelve hours a day on a book, “crying the whole time.” In “Ancient Tillage,” the strange, short novel he wrote, a young man flees his rural home and family, only to return, chastened and a little humiliated, to the place of his childhood.

“Ancient Tillage” was published in 1975, to immediate critical acclaim. It won the best-début category of the Jabuti prize, Brazil’s main literary honor, and another prize from the Brazilian Academy of Letters. In 1978, a second novel appeared in print; Nassar had written the first draft of “A Cup of Rage” in 1970, while living in Granja Viana, a bucolic neighborhood on the outskirts of the city. It, too, was received euphorically, winning the São Paulo Art Critics’ Association Prize (acpa). “Those two books had a very strong impact,” Antonio Fernando de Franceschi, a poet and critic who became a close friend of Nassar’s, told me. “They are small, hard rocks. Everything is concentrated there.” Last year, Nassar’s two novels were translated into English for the first time, for the Penguin Modern Classics Series—New Directions will publish them this month in the U.S.—and “A Cup of Rage,” translated by Stefan Tobler, was longlisted for the Man Booker International Prize.

Nassar’s novels quickly caught the eye of publishers in France and Germany and, by the early nineteen-eighties, with two short books that together amounted to fewer than three hundred pages, he was already being hailed as one of Brazil’s greatest writers, mentioned in the same breath as Clarice Lispector and João Guimarães Rosa. On visits to Paris, he was invited to speak at the Sorbonne, and doted on by the publishing heir Claude Gallimard and the famous Catalan literary agent Carmen Balcells. A close friend to Gabriel García Márquez, Mario Vargas Llosa, and Pablo Neruda, whose estates she looked after, Balcells is often thought to have been responsible for the vaguely defined but highly marketable concept of the Latin American Boom, a growth in the global appetite for the region’s literature during the nineteen-sixties and seventies. Back then, she sought out Nassar to join the club. “She expected something big,” he told me last year, when we met for the first time, at his home in São Paulo. “She was a very generous person.”

Nassar was forty-eight and at the height of his literary fame when, in 1984, he gave an interview with Folha de São Paulo, the country’s biggest daily newspaper, in which he announced his retirement. He wanted to become a farmer. “My mind is lit up with other things now; I’m looking into agriculture and stockbreeding,” he told the interviewer. Many were baffled. Nassar kept his word. The following year, he bought a property of roughly sixteen hundred acres and began to plant soy, corn, beans, and wheat.

“I gave up a lot of things then, you have no idea,” he told me that afternoon. Nassar, who is now eighty-one years old, lives alone in a discreet, red-brick building in one of the quieter parts of Vila Madalena, a bohemian neighborhood on the city’s west side. In 2011, after almost three decades spent tending to crops, Nassar donated his land to the Federal University of São Carlos, on the condition that they build an extra campus to give better access to rural communities. The campus is now up and running; Nassar spoke of a former farm employee whose daughter was studying there.

Nassar’s living room is sparsely furnished, with an old, yellowing clock on the wall and a black-and-white portrait of his parents above his desk. There are no bookshelves in the living room, but there was a short row of books on the mantelpiece: André Gide, Dostoevsky (a writer he especially loves), and many old volumes of Caldas Aulete, a Portuguese dictionary. I noticed haphazard piles of crisp new books on his side tables and couch. “Those are gifts,” he said. “I tell people I don’t read anymore, but they never believe me.”

Writers who choose not to exercise their talents can provoke a range of reactions in readers and fellow-writers, from envy to exasperation to awe. Nassar’s early retirement was received in Brazil with a sort of fascination tinged by a hint of offense. In deciding to become a farmer—not an idle dweller but the owner of a productive, medium-sized fazenda—he had downgraded the status of literature…

Read the whole profile here.

Share this: