Image credit: Elizabeth Butler, Remnants of an Army (1879) Tate Gallery

I have finished reading William Dalrymple‘s mesmerising and tragical history of the first Anglo-Afghan War (1839-42), Return of a King: the battle for Afghanistan. It tells the story of the British invasion of Afghanistan, or, as it was known by its local rulers then, Khurusan.

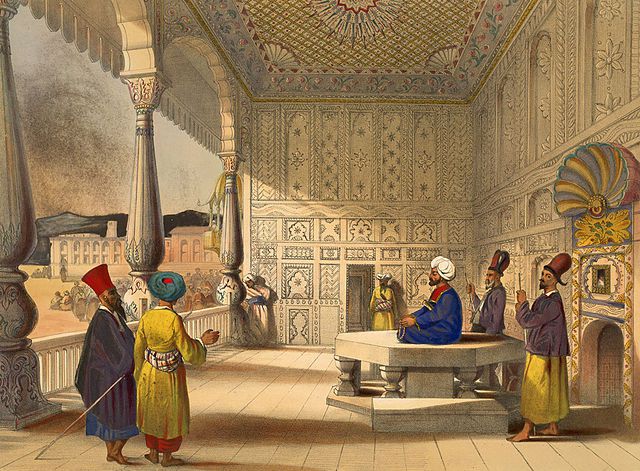

The king who returns in this story is Shah Shuja of the Sadozai dynasty, who is depicted below holding court in the Bala Hissar fort and royal palace of Kabul.

Image Source: Interior of the palace of Shauh Shujah Ool Moolk, Late King of Cabul, 1839, Lithograph by Lieutenant James Rattray, British Library Online, Wikimedia Commons .

In 1800 the Sadozai dynasty had been ousted by its main rival, the Barakzais. The Barakzais clan would be led ultimately by the formidable Dost Mohammed Khan (1779-1863). Shah Shuja lived in exile in Ludhiana in the Punjab, and suffered many humiliations and defeats in his efforts to reclaim the throne, not least yielding the Koh-i-Noor diamond to Maharajah Ranjit Singh, the Lion of Punjab, one of the most effective military rulers who resisted the British. The British made a strategic decision to ally with Shah Shuja. They supported him with a pension, and kept his tattered court intact for thirty years before deciding in the 1830s to reinstall the Shah as ruler of Khurusan.

The British motive to return this King was geo-strategic rivalry with Russia, and the secure control of Britain’s Indian Empire. Fears were spread in doctored intelligence reports that the Russians planned to take control of Afghanistan, ally with Persia, and squeeze Britain’s imperial heart from the north. These fears were unfounded, but give Dalrymple’s book some of its most intriguing and tragic characters – the three key local intelligence officers of Britain and Russia, Alexander Burnes (a relative of poet, Robert Burns) and his Afghan colleague Mohan Lal Kashmiri, and Ivan Vitkevitch or Jan Prosper Wietkiwicz. These three were the central players in the opening gambit of the Great Game of espionage and geo-strategic rivalry in Central Asia between Russia and Britain. All their lives ended tragically, perhaps none more so than Wietkiwicz. He had been exiled and sentenced to death at the age of 14 for opposing Russian rule of his native Poland. His death sentence was commuted and he made a life as an extraordinary military officer, linguist and early intelligence officer in the Russian army, which he had resented as an adolescent. He outwits the British, and achieves Russia’s initial objectives of securing an alliance with the Barakzai clain, but then is withdrawn as Russia makes a diplomatic pivot. He dies suspiciously in St Petersburg in an apparent suicide on the eve of being honoured by his Tsar, but some historians, including Dalrymple, credit a plausible hypothesis that he was assassinated by British agents.

These men’s lives were consumed and destroyed by rulers and decision-makers full of delusions and misjudgements. The mystery at the heart of the book is the incompetence of power. Why did the least able generals, diplomats and rulers control the command boxes, while the able ones were shunned, ignored, overlooked and slighted? The greatest tragedy that flows from that incompetence is the invasion of Afghanistan, ordered by the remote and inattentive governor, Lord Auckland, executed with ferocious stupidity by Major-General William Elphinstone, and overseen politically by the pompously self-certain, deluded Sir William Hay McNaghten.

The invasion began with a disastrous unprotected march through the Bolan Pass, where the British army, principally made up of Indian sepoys and camp followers, was attacked by snipers from the high cliffs, and lost most of its supplies. Still, they made it through and were surprised by the withdrawal from Kabul of the Afghan rulers. The British took it over and engaged in outrageous looting and destruction of some of the commercial centres of Kabul. They reinstalled Shah Shuja as a puppet ruler, and settled in for a year or more of British proxy rule. That rule was characterised by arrogant misjudgements and contempt for the local population, and even Shah Shuja himself. McNaghten was the real ruler of Afghanistan, and he inspired an Islamic uprising against mistreatment and foreign infidel rule.

Dost Mohammed had withdrawn strategically to gather his strength. By 1841 he marched his armies and coordinated a network of urban insurrection. The British were trapped in Kabul, and overrun by this urban insurrection. Alexander Burnes – a figure of hate in Afghanistan for his espionage and his private harem of Afghan women – was murdered. Dost Mohammed outsmarted by the vain British rulers. He offered them safe passage out of Kabul. In reality he continued to harry and attack the retreating army, shepherding it into ambush after ambush, while claiming these attacks were made by uncontrollable rival tribes. Almost the whole retreating army and its camp followers died or were captured and sold into slavery in the most terrible scenes. Starving, frostbitten husks lined the mountain passes to Peshawar. Ultimately, a single man – the British surgeon who survived misadventures through luck more than heroism – rode alone and exhausted into the last British stronghold of Jalalabad. This is the scene depicted in Elizabeth Butler’s Remnants of an Army (1879).

Shah Shuja had earlier been attacked on his march out of Kabul by a band of vengeful Afghani warlords who he had alienated and offended. His palanquin was found and attacked. The last Shah of the Durrani empire, the last Timurid ruler of Khurasan, was shot and left to rot in the barren sands outside Kabul. The British had done much to ruin Afghanistan. It would no longer be a commercial cross-roads of Central Asia. Still, Dost Mohammed ruled successfully for another twenty years, increasing the revenues and security of his country. He would become a national hero, but still an imperial “war for no wise purpose” had wrecked so many lives.

In another of Dalrymple’s histories of Mughal India, The Last Mughal: the Fall of a Dynasty, Delhi, 1857 (2006), he writes:

Public, political and national tragedies, after all, consist of a multitude of private, domestic and individual tragedies. It is through the human stories of the successes, struggles, grief, anguish and despair of these individuals that we can best bridge the great chasm of time and understanding separating us from the remarkably different world of mid-nineteenth century India (p. 13)

The Return of a King is a masterpiece in bridging that chasm through the interweaving of exceptional individual stories with profound public tragedies, and the presentation together of uncanny contemporary parallels with all the strangeness of a lost but recoverable world.

Advertisements Share this: