This review appears on paperbackparis.com:

This review appears on paperbackparis.com:

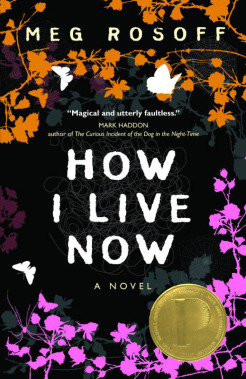

Meg Rosoff‘s 2004 novel, How I Live Now, is eerily prescient. At the time of its publication–only three years after 9/11–the dystopian world in which our protagonist, Daisy, and her cousins live could have seemed like the reality we were headed towards. While it has always been true that, at any given time, parts of the world are besieged by the atrocities of war, most inhabitants of the West cannot conceive that our societal structures will collapse. That kind of endless violence–the inevitable outcome of hundreds of years of colonialism and imperialistic greed–happens to others in “those parts of the world.”

How I Live Now tears down this facade of safety. 15-year-old Daisy, a spirited teenager with anorexia, is sent to stay with her Aunt Penn and cousins in England. Her father and his new wife have little space in their new lives for Daisy, and everyone agrees that a summer away from New York will do her good. When she reaches England, terrorist attacks have blossomed all over the world, and security is high. But her cousins’ life in the countryside is secluded from the dangers in London and other cities.

Homesick at first, Daisy finds herself isolated from their insular world. Aunt Penn keeps odd hours and travels often for her work. Osbert, the oldest cousin, takes on a superior role to his brothers and sister. He keeps track of the war we discern as World War III while the others go about their chores and games. Twins Edmond and Isaac, along with their young sister, Piper, possess preternatural abilities when it comes to understanding the earth and other people’s unspoken thoughts.

Soon enough, Daisy is completely wrapped up in their world–an idyll in the midst of a brewing storm. Aunt Penn has to attend a conference in Oslo shortly after Daisy’s arrival, so the children are alone in the house. Rosoff’s sparse narrative captures the lushness of summertime and the young love that blooms between Daisy and Edmond. The taboo of their incestuous relationship is mitigated by the circumstances the children find themselves in. Right after Penn leaves, a nuclear bomb goes off in London, and their isolation is complete. They live off of government rations and what grows on the farm.

Daisy and Edmond–two lost souls–are bound together by more than family ties. The chemistry of their blood and bones and the way they can know each others’ thoughts without saying a word becomes a refuge. They make promises to never leave each other.

Of course, their summer sanctuary goes as soon as it comes. Osbert, eager to contribute to the war effort, offers their home as a barracks for a local regiment. The children are separated from each other. Daisy and Piper are sent to live with an army officer and his wife. The boys are sent to another farm nearby. While Daisy’s days are consumed with physical labor, she and Edmond still communicate with each other through whatever invisible rope that holds them together. He is in her mind, telling her stories, bringing them peace.

But violence erupts again. Daisy and Piper are forced to flee. They make their way towards the others only to be confronted by mass slaughter. In this moment, the vertiginous out-of-body experience that accompanies the sight of heinous carnage takes over Daisy and Piper. Rosoff’s brutal sentences convey the horror of the atrocities they encounter without falling into hyperbole or melodrama. The facts are what they are. The horror of the images speaks volumes without prodding.

Eventually, Daisy’s father brings her back to America. She leaves home as soon as she can to work in the New York Public Library. Living to see the end of each day is a gamble, but she is determined to make it back to England. When she finally goes back seven years later, the farm is still the sanctuary it once was. Daisy learns what happened to Osbert, Isaac, and Edmond all those years before. They made it out. But Edmond is a shell. He hates Daisy for breaking their promise. For leaving.

Daisy begins the process of salvaging what was lost, rebuilding the structure of their happiest days. Despite all that’s happened, the novel ends on a hopeful note. Daisy will stay in England with Edmond and the others and live out the rest of their years in peace.

How I Live Now is a gorgeous, heartbreaking reflection on war and sanctuary. In just a 192 pages, Rosoff explores the ways in which young people can build worlds for themselves outside of what society claims is right. Through a deep connection to the earth and the natural world, Daisy and her cousins shape a niche under the weight of world-ending terror. In a world that is starting to appear more and more like that in How I Live Now, this story of love and resilience resonates as strongly as it did over a decade ago.

Share this: