Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945 by Tony Judt

Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945 by Tony Judt

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

History is a discipline peculiarly impervious to high theoretical speculation: the more Theory intrudes, the father History recedes.

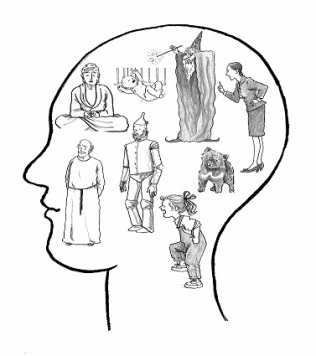

When I was in university, studying anthropology, I always resented the requirement that my essays have thesis statements. Can’t I just collect information and serve it up without taking some ultimate stance? Tony Judt seems to have been of the same mind, since this book is one very large serving of information, absent of any overarching thesis. As he says himself, Judt is rather like the proverbial fox than the hegdehog: he knows many things, and has many valuable observations scattered throughout the text, without any one big idea to tie them together.

There are compelling advantages to this approach. This book is one-stop shopping for many aspects of post-war European life. Economic development, intellectual fashions, architecture, film history, political movements, the Cold War, regionalism, the emergence of the European Union—all this and more is covered in impressive detail. And though multifarious, all of these pieces come together to form an astounding story: a continent nearly destroyed by war, divided by dangerous political tension, slowly emerging from American and Soviet dominance to become the most affluent, most peaceful, and most progressive place in the world.

The main disadvantage of this method is, of course, that this story remains fairly messy and haphazard. Without a thesis to guide him, Judt had to rely on a mixture of interest, instinct, and whim—the latter playing an especially significant role in some sections. What is more, though Judt is an opinionated and assertive guide, the lack of a thesis renders it difficult to point to anything distinctly “Judtean” in his analysis. What ties the narrative together is, rather, a certain mood or sensibility—most notably, Judt’s keen sense of historical irony, which he employs to great effect.

This ironic sensibility is most often directed toward Judt’s political foes. Though he is never explicitly partisan, it is easy to tell where Judt’s sympathies lie: in the center-left, socialist-democratic camp. Thus, depending on where the reader falls on the political spectrum, Judt’s comments will be either gratifying or grating. For me they were usually the former. What irked me, instead, was Judt’s relatively brief treatment of Spain—the Franco era is entirely ignored, and the transition to democracy is covered in just a few pages. But this is admittedly my own prejudice speaking.

If Postwar has one takeaway message, it is this: that Postwar Europe is the anxious construction of a generation wearied and horrified by conflict. After going through the belligerent nationalism of the First World War, the economic depression and intense ideological polarization of the interwar period, the even more gruesome Second World War and the unspeakable Holocaust—all this, coupled with the prolonged armed standoff and Soviet repression of the Cold War—Europeans were intent on creating a world where this could never happen again. Extreme ideological stances fell into disgrace; strong government social safety nets helped to prevent economic crisis and, in so doing, made people less susceptible to demagogues; and governments forged institutional ties with one another, a project that culminated in the European Union.

Without constant reminders of this catastrophe—a European civil war that began in 1914 and whose political aftereffects did not disappear until 1991, if then—we risk falling into the same errors that tore the continent apart one hundred years ago. For this, we need good historians—and Judt is certainly among the best.

View all my reviews

Advertisements Share this: