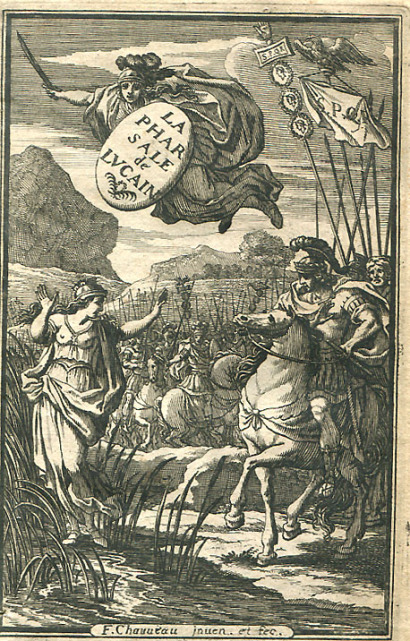

‘aduenisse diem qui fatum rebus in aeuum conderet humanis, et quaeri, Roma quid esset,

illo Marte, palam est.’

‘It is clear, the day which will decide the matters of human life forever has come,

the battle shall decide what Rome shall be.’

-Lucan, Civil War, 7. 131-133.

Attribution: Engraved title page of a French edition of Lucan’s Pharsalia, 1657.

Attribution: Engraved title page of a French edition of Lucan’s Pharsalia, 1657.

How did the young poet Lucan (39-65 AD), writing his epic poem, the Civil War, under the erratic Emperor Nero, manage to explore and engage with the notion of revolution, a term which would wait more than a thousand years to be coined in its current sense?

Though there is no identical Ancient Greek or Latin word for the drastic and fundamental political change we have come to associate with revolution, the ancients were by no means unfamiliar with such periods of transformative upheaval. Herodotus, the ‘father of history’, acknowledges fortune’s fickle loyalty when he describes the inevitable rise and collapse of cities, states, and empires, in the opening of his monumental historical treatise. Aristotle and Thucydides use the broad term ‘stasis’, which hints at disagreement, dispute, and internal conflict, in their discussions of feuding factions and disruptive civil strife. The ancient tradition drew clear lines between foreign and civil war, the former an opportunity for riches, glory, and the spread of superior culture and ideology, the latter the worst kind of crime, akin even to familicide. So how can we think about Lucan’s civil war poetry in terms of revolution while it so clearly carries the taboos of sin and violation?

When I read Lucan’s Civil War, an epic poem in ten books depicting the civil war between Pompey and Julius Caesar which heralded the fall of the Roman Republic, I am struck by the innovative skill with which Lucan handles this transformative period. Lucan offers frequent authorial interjections, stating and restating that he is narrating a pivotal moment, a turning point, a climactic crossroads in Roman history.

In this conflict, we find not a sweeping and all-encompassing revolution of banners, barricades, or the intrepid uprising of the downtrodden to challenge their oppressors. Instead, we are faced with the conflagration of two men’s ardent ambition to seize ultimate control of Rome and her empire. Within this zealous dance of desire, Lucan explores the themes of liberty and tyranny, lamenting the loss of the former, and condemning the development of the latter into the modus operandi of the period. Caesar and Pompey, the two pro-/an-tagonists, are among only a few individuals to be clearly named or identified by Lucan. And yet, Lucan manages to portray the civil war as a conflict which involves and impacts the entire world, a dispute between two individuals which swallows up the lives of innumerable unnamed men in its violent and irreversible re-writing of the Roman world.

Lucan’s story begins with Caesar’s legendary crossing of the Rubicon River (‘the die has been cast’), and takes his reader on a journey around the ancient Mediterranean, to the bloodstained battlefields of Thessaly, to the snake-infested deserts of Libya, and the ruins of Troy. Around the civil war’s historical skeleton of engagements, routs, sieges, and defeats, Lucan weaves a rich textual body, incorporating diverse, unfamiliar, and revolutionary material. We encounter ahistorical and impossible scenes – visions, ghosts, and even a fantastical necromancy – which share the themes and motifs of the main narrative which unfolds around them. Lucan’s necromancy, performed by the monstrous Thessalian witch, Erictho, explores dark and controversial magical rites, paradoxical addresses to otherwise silent gods, the violent reanimation of a fallen soldier, whipping the narrative’s themes and tensions into a climactic frenzy even before we arrive at Pharsalus, the decisive battle of the civil war. These passages connect Lucan’s rendering of the civil war with elements of Roman religion, culture, and superstition which are disturbed or even disarmed by a conflict which pitches Roman standards against Roman standards, Roman spears against Roman spears, Roman kin against Roman kin.

When we think of epic poetry, we think of grand and monumental works singing of heroic deeds and events deeply rooted in a nation’s collective culture, works such as Virgil’s Aeneid or the later La Chanson de Roland. In choosing to compose a work detailing a pivotal historical moment of revolutionary political change, Lucan appears to embrace the nature of the epic medium. However, in using such a public and elevated art form to explore the controversial theme of civil war, Lucan seems to challenge and subvert the very cultural values which raised up the epic genre as a platform for representing events and material of national importance. It is only when we look closely at Lucan’s writing, that we realise that this paradoxical act of simultaneous acceptance and subversion, of rendering this impactful and revolutionary conflict in grand and yet unconventional terms, Lucan is enacting a revolution of his own.

Elaine Sanderson is a second-year PhD student at the University of Liverpool in Classics & Ancient History. The subject of the submission relates to her main are of research, Lucan’s ‘Bellum Civile’. Other research interests include Flavian epic poetry, ancient rhetoric, Sophoclean tragedy and classical reception in opera.

Advertisements Share this: