Himalayan Balsam

Himalayan Balsam

Pioneering research carried out by scientists from Royal Holloway and the University of Reading in collaboration with CABI is looking to enhance the effectiveness of the biological control of invasive species. The team is using rust fungus (Puccinia komarovii var. glanduliferae) to control the invasive species, Himalayan balsam (impatients gladulifera), and developing ways in which this approach could be replicated for other invasive plant species.

Himlayan balsam dominates the banks of the UK’s rivers and waterways, eradicating native plants and leaving soil exposed to erosion during the winter. Although it dies off in colder months, research has found that the plant has actually caused changes in the soil microbiota meaning that native plants are not able to re-colonise during this time. Further problems are also caused by the plant clogging waterways as well as its potential to attract pollinators required by other species.

The use of herbicides is ineffective in controlling the Himalayan balsam due to its proximity to waterways and although regular removal by volunteers has been valuable, it is slow and costly in terms of labour. Therefore the introduction of a biological control agent would be a novel and environmentally friendly method of reducing and controlling the invasive population.

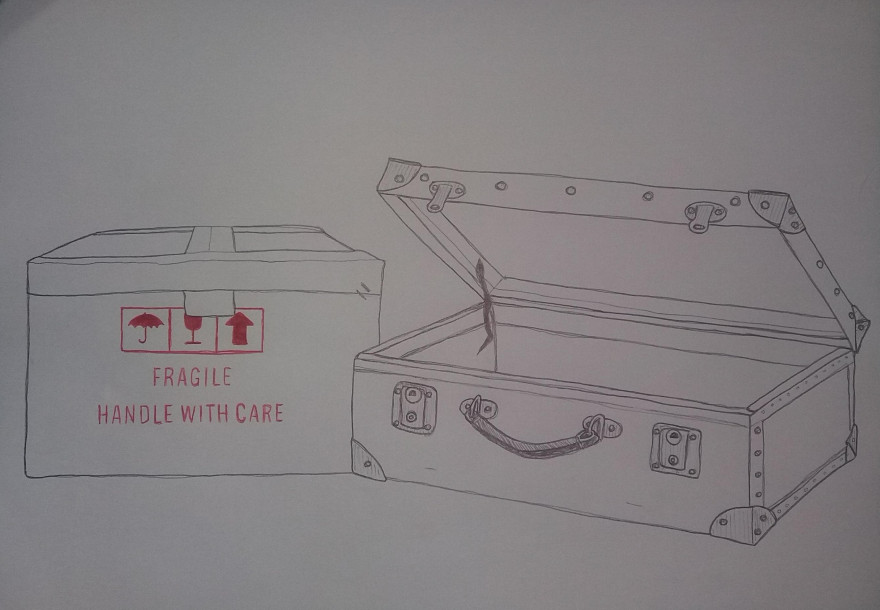

Himalayan balsam leaf showing the effects of rust fungus

Himalayan balsam leaf showing the effects of rust fungus

Lead researcher, Professor Alan Gange outlines the study, “we are conducting experiments to see if fungi inside leaves (endophytes) and inside roots (mycorrhizas) can affect the ability of the rust fungus to infect Himalayan balsam.” After a year in the lab, the results of team’s experiments show dramatic effects of each fungal group on the other. Going into the second year of the project means taking the experiments into the field where things get much more complicated. This is where the team will also get to assess the microbiome of the Himalayan balsam to see if the application of rust fungus starts to damage the plant so that the microbial community around the roots and inside the plant changes, and whether this change is beneficial or not. By comparing both treated and untreated plants, the team will be able to see differences such as whether an increase in microbes means that they are detrimental to plant health or act as an indicator of plant decline. As well as recording any effects on the plant and soil, the CABI team is also looking at the recovery of native plants and invertebrate communities after the introduction of the rust fungus.

The decision to utilise rust fungi, says Dr Carol Ellison from CABI, was because they “are often extremely host specific, sometimes only infecting a limited number of genotypes of the target weed, which makes them very safe to use.” There are also a number of other examples where the fungi have proven to be an effective and sustainable long-term solution for controlling individual invasive plant species.

Whilst biological control has its many benefits, it does not come without obstacles. Even if the agent is ready to be introduced, there can be conflicts of interest with various stakeholders in the field. Certain invasive species provide natural shelter for farm animals, they can be a source of firewood, or could even hold monetary value as an ornamental plant. Undertaking detailed consultations are as important as the science in ensuring suitable release of control agents. In other cases, insects introduced as control agents have themselves been controlled by local predators that were suddenly able to feast!

The research is vital to the future of biological control as it opens the door for using this approach across a wide variety of alien species; contributing to growing literature that looks beyond pesticides. The rust fungus has been introduced into a selection of field sites and its impact is being observed in a number of ways. The priority is monitoring the effectiveness in reducing plant population but in future the team are also looking at recovering native species in place of the Himalayan balsam and the impact of changing plant populations on the soil microbiota and local insect populations.

Find out more in this fascinating Q&A with the research team.

Rate this:Share this: