A sad confession by way of a short prologue.

One of my main Christmas delights is watching the Christmas season of University Challenge, the highbrow BBC quiz show where teams of undergraduates and postgraduates, each with a brain the size of a planet, form teams representing their university or college and answer fiendishly difficult questions on all, sundry and often obscure areas of knowledge, with me dear old mum. The downside is that I am now addicted to it. So deeply am I hooked, I have now started watching series from years gone by, handily available on YouTube. I get a real kick out of answering questions before the boffins can reach their buzzers, though I have to remind myself that nearly all the answers I give (yes, I shout them out loud) are things I have learned SINCE my university days, and certainly not before the age of 20, which the majority of these brainiacs are. Hats off to them. So, I do OK on literature, languages, popular music, art and anything to do with food. Sometimes there are questions that involve a bit of mental arithmetic, and I occasionally get there (though I pause the video and call out the answer before then unpausing and still feel smug that I answered before they did. I told you this was a sad confession).

Apart from the advanced maths or quantum physics questions or anything to do with  kings or queens which I just filter out, the one thing that bugged me I was utterly pants at was classical music. Vivaldi sounded like Mozart to me, Bach and Handel were indistinguishable, Rimsky-Korsakov and Shostakovich little more than names which it is fun to say in a rich Russian accent. I decided to change this. My drive to put one over on the boffins is bordering on the obsessive. (Some might say I have crossed the border and am skipping blithely through the Kingdom of Idée Fixe.)

kings or queens which I just filter out, the one thing that bugged me I was utterly pants at was classical music. Vivaldi sounded like Mozart to me, Bach and Handel were indistinguishable, Rimsky-Korsakov and Shostakovich little more than names which it is fun to say in a rich Russian accent. I decided to change this. My drive to put one over on the boffins is bordering on the obsessive. (Some might say I have crossed the border and am skipping blithely through the Kingdom of Idée Fixe.)

So, after a brief search on the web on ways to improve my knowledge, I happened across a great site (I’m not getting paid to plug them) called Memrise. A large part of what they do is dedicated to the learning of languages (which I haven’t dipped into yet), but there is a music section (also all other aspects of the arts, maths and science, the natural world, history and geography, etc., etc.). I tried a course called ‘Who composed me?’ and was almost instantly hooked.

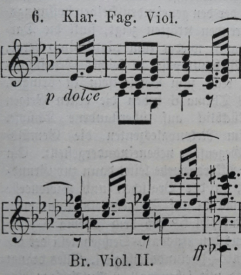

You start off by hearing snippets of well-known pieces by half a dozen famous classical composers, while they show you their name and a picture of them. They then give you the chance to hear them again, and pick out the composer’s name from a list, then you see the composer’s name and have to find the right piece of music by hovering over and listening to four options, and then you hear the piece and have to write in the correct composer’s name (they accept surname only, thankfully). All the while, new names get dropped in and they also get fed into the varied rounds of recognition and distinction tasks until you are able to hear a piece of music and key in the composer’s name. I L-O-V-E-D it. For a start, it’s nice and varied and you get the chance to recognise before producing, so to speak. Secondly, there are no penalties for wrong answers, there are no discouraging noises (or sniggers) when you claim that Brahms is Liszt or vice versa and third it is TOTALLY INTERLEAVED! (excuse the shouty capital letters). You never know what’s going to pop up next, it might be a whole new name and piece of music, it might be one they’re recycling from before, it could be recognition from a list or typing in the name – it’s all mixed up and I couldn’t have hoped for a more successfully interleaved approach if I’d tried to design it myself.

As a result, I can now hear pieces of music by Brahms, Liszt, Smetana, Beethoven, Prokofiev, Tchaikovsky, Grieg, Strauss (younger and elder and Richard), Barber, Copland, Elgar, Mussorgsky, Rachmaninoff, Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Chopin, Debussy, Mahler, Satie, Delibes, Dvorak, and various others who I can’t remember off the top of my head, but whose music (mostly) rings an instant bell. I still get Chopin and Schubert mixed up now and again, and Fauré and Saint-Saens still sound a bit similar to me, but I’ve made a huge jump forward, and had lots of fun into the bargain.

As a result, I can now hear pieces of music by Brahms, Liszt, Smetana, Beethoven, Prokofiev, Tchaikovsky, Grieg, Strauss (younger and elder and Richard), Barber, Copland, Elgar, Mussorgsky, Rachmaninoff, Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Chopin, Debussy, Mahler, Satie, Delibes, Dvorak, and various others who I can’t remember off the top of my head, but whose music (mostly) rings an instant bell. I still get Chopin and Schubert mixed up now and again, and Fauré and Saint-Saens still sound a bit similar to me, but I’ve made a huge jump forward, and had lots of fun into the bargain.

I really think the interleaving approach has helped greatly. There was no grouping by nationality, era or style, they just chucked stuff at you (at a reasonable pace) and you learn to feel your way. Of course, this one-off anecdotal experience is not scientific proof of anything. I had no way of making a ‘control group’ with one bit of my brain which studied another set of composers or pieces of music in a more ‘traditional fashion and comparing the learning outcomes.

But…It’s not to everyone’s taste. According to various writers on the topic and as mentioned in previous posts (1, 2) on this blog, it’s one of those techniques which is difficult to introduce into the classroom or persuade people to do for their own learning, as it involves switching to something different exactly when you feel you’re getting a feel for what you want to learn. There is something entrenched in our brains which says ‘I don’t give a monkey’s if it’s good for me, just let me finish!!!’ It’s akin somehow to the all-too-common mindset which says ‘Yes, I know I should take the whole course of antibiotics, but I’m feeling better now, so…’

Why do we resist things which we’ve been reliably told are good for us, but somehow don’t seem to quite fit into our outlook?

I did warn you there’d be basketball.Malcolm Gladwell (author of The Tipping Point, Blink, Outliers, What the Dog Saw and David and Goliath) has an interesting take on this in his brilliant podcast Revisionist History. He focuses in one episode on Wilt Chamberlain, one of the greatest basketball players of all time (according to some, better than Michael Jordan, Kobe Bryant or Meadowlark Lemon) and the only player to ever score 100 points in an NBA game. In fact, to show just how far ahead of the pack he was – get this statistic: only four players have scored 60 or more points on more than one occasion – Kobe Bryant did it six times,  Michael Jordan did it five times, Elgin Baylor four times and Wilt Chamberlain THIRTY-TWO TIMES! What Chamberlain sucked at, however, was free throws (after a player has been fouled and they have a chance to throw a basket twice for a point each). Most top players make 80-90% of these throws. Chamberlain often struggled to make 50-60%. This made him a liability on the court if the game was tight and time was running out.

Michael Jordan did it five times, Elgin Baylor four times and Wilt Chamberlain THIRTY-TWO TIMES! What Chamberlain sucked at, however, was free throws (after a player has been fouled and they have a chance to throw a basket twice for a point each). Most top players make 80-90% of these throws. Chamberlain often struggled to make 50-60%. This made him a liability on the court if the game was tight and time was running out.

But salvation was at hand! A player and coach called Rick Barry taught him how to raise his score dramatically by throwing ‘underhand’. The trajectory of the ball starting lower and making a higher loop means that it has a much better chance of dropping straight in the basket and much less of bouncing off the rim which happens with the more narrow-looped shot which most players use. Chamberlain used this underhand technique (it contributed to his legendary 100-pointer) and made 28 out of 32 free shots. Unheard of for him and a major contribution to his being an all-time hall of fame player for that mythical game.

Then the next season, he abandoned it and never used it again. Why?!? It’s known in the game as ‘granny style’ and it doesn’t look cool (see here for an example of the only NBA player to use the technique in years). In fact it looks downright laughable to die-hard basketball fans. Only your granny, the name suggests, would walk on court and throw like that, and admirable as grannies may be, they are not known for being cool. Never mind if it’s proven to be the best method and the proof is right there before your eyes and on your scorecard. Forget it, said Wilt. I AIN’T doing it.

Gladwell calls this reaction the high threshold reaction. The higher your threshold, the more difficulty you have in accepting new ideas. Most of us set our thresholds high and new approaches have to struggle to get past or over that high bar we set. Only when everyone else seems to be starting to do it will we cede and give it a go. The granny shot has never caught on in professional – or any – basketball. High, high threshold.

Gladwell calls this reaction the high threshold reaction. The higher your threshold, the more difficulty you have in accepting new ideas. Most of us set our thresholds high and new approaches have to struggle to get past or over that high bar we set. Only when everyone else seems to be starting to do it will we cede and give it a go. The granny shot has never caught on in professional – or any – basketball. High, high threshold.

The same seems to apply to interleaving. Years of being told to practise, practise, practise the same thing over and over again, and there seeming to be visible results for this (though, as I posited earlier, probably not for the reasons we think) have set our threshold for new learning strategies very high. I think I know how to learn, thank you VERY much! Really! It’s like trying to get my stepdaughter, Edna, to eat vegetables. Well, you SAY they’re good for me, but I seem to be doing just fine on meat and rice, so… no thanks!

No way, no how! Wait, did you just…?And so I sneak broccoli into the pasta bake, peas into the rice, and lettuce (exempt for some reason) everywhere I can stuff it. I mostly get away with it. And I do the same with my students. Pop quizzes, regular ‘revision’ exercises, lessons where we ‘tidy up unfinished bits and pieces’ or ‘preview’ what’s coming in the next month and the use of varied and entertaining stimuli mean the broccoli/pea-like goodness of interleaving gets wedged into their learning without them screwing up their faces and spitting.

I worry, though, that I’m not preparing them for the big bad outside world where knowledge of the good that interleaving can do them would be a boon. Will they thrive…? Then again, word has come through that Edna – living away from home for the first time in her first term at university – made herself black beans and rice for dinner last week! With frozen chicken nuggets. Baby steps.

Share this: