By Howard “Cork” Hayden,

A few years ago, I learned of an article by Mark Z. Jacobson and Mark A. Delucchi in the November 2009 issue of Scientific American called “A Path to Sustainable Energy.” My first impression was, “These guys must be joking.” My second impression was, “Yes, they are joking, and the joke is on Scientific American.” Jacobson and Delucchi wrote a spoof to show what tomfoolery can be published in Scientific American, rather like Alan Sokal’s spoof of post-modernist jargon in Social Text. They did manage to squeeze in some calculations that detail what is really involved in a carbon-free economy, but avoided all precautionary words, lest the editors reject the manuscript. It’s a laugh a minute.

The authors have humorously gone way beyond Al Gore’s challenge to “to repower America with 100 percent carbon-free electricity within 10 years.” They have a plan “to determine how 100 percent of the world’s energy, for all purposes, could be supplied by wind, water and solar [WWS] resources, by as early as 2030.”

I suppose that if the authors had suggested power lines directly from wind farms to C-5A air transport planes, the editors of Scientific American would have caught on, but the ever-practical Jacobson (civil engineering professor at Stanford) and Delucchi (transportation expert at the University of California-Davis) used a more subtle approach.

For example, their analysis concluded that nuclear power was a poorer option than wind, solar, geothermal, tidal, and hydroelectric power because some CO2 is produced when the plant is built and when the fuel is refined. Just think of all the CO2 released when they make concrete for the containment building. J&D correctly surmised that the editors wouldn’t think of the hundreds of times more concrete would be used in the bases for the wind towers required to replace a nuclear reactor. Ditto for the steel.

On that topic, there is a lot of CO2 released when uranium is refined; gosh, that electricity comes from coal-fired power plants. It would never occur to the Scientific American editors that the electricity could come from nukes instead, so Jacobson and Delucchi (J&D) could slip that right under their noses without fear that the editors would detect the spoof.

I have no idea how J&D got one patently absurd thought past the Scientific American editors, but it must have worried them that the spoof would be discovered. A J&D chart with some colored dots to represent coal, wind, and PV showed that coal plants are down on average for 46 days a year, whereas wind and photovoltaics only have 7 days of downtime. (If only the wind would blow, our turbines will work!) They say,

The average U.S. coal plant is offline 12.5 percent of the year for scheduled and unscheduled maintenance. Modern wind turbines have a down time of less than 2 percent on land and less than 5 percent at sea. Photovoltaic systems are also at less than 2 percent.

A savvy editor would ask how much uptime they have. As a matter of fact, a savvy editor would know that the annual capacity factor of a coal plant is well over twice that of wind and 4-to-5 times that of PV. But that only shows that J&D are excellent spoofers, who recognize the gullibility of the Scientific American editors.

The spoof continues. Their mix of sources contains 1.7 billion rooftop solar photovoltaic systems, each of 3 kilowatts. They note that less than 1% of these are in place. True enough. If they were serious, they would have used a much smaller number. “Less than 1%” covers a lot of territory. Less than 1% of all men are 2.0155 meters tall with one green eye and one brown eye, yellow hair, a gray beard, a broken ankle, and only their four wisdom teeth in their mouths.

Let’s see. The world population is 6.7 billion. Likely, there are 5 people per household, making about 1.3 billion homes, some of which are single-family homes with good sunlight. (The US and Europe have anomalously low family size.) So, precisely where might these 1.7 billion sun-baked rooftops with southern exposure come from? J&G slipped another one past the number-challenged editors.

Perhaps the strongest clue that J&D wrote a spoof is that the hallmark of good engineering is overweening practicality. Given their fantastic credentials in California universities, one would expect an article by the authors to be intellectually brilliant, solidly analytical, and exquisitely practical. As their Scientific American article is none of the above, it was obviously intended to show that you can publish anything in Scientific American so long as it is fashionable nonsense.

So taken were Scientific American’s editors by the erudition[1] of the J&D article that they use the headline: “Wind, water, and solar technologies can provide 100 percent of the world’s energy, eliminating all fossil fuels.” J&D must have told the editors that their calculator said so.[2] If you know what they’re doing, these guys are funny!

It is extremely easy to solve problems if there are no constraints. A good example is in an ancient joke. “How do you get four elephants into a VW?” “Easy. Two in the front, two in the back.”

J&D joke: “How do you get all of the world’s energy from wind, water and solar?” “Easy. 490,000 tidal turbines, 5,350 geothermal plants, 900 hydroelectric plants, 3,800,000 5-MW wind turbines, 720,000 wave converters, 1,700,000,000 3-kW rooftop solar PV systems, 49,000 concentrated solar power plants, and 40,000 300-MW solar PV power plants.”

In a later Stanford publication [1], Jacobson and Cristina Archer (Associate Professor at the University of Delaware) wrote, “Thus, there is no fundamental barrier to obtaining half (approximately 5.75 TW) or several times the world’s all-purpose power from wind in a 2030 clean-energy economy.” [Emphasis added]

Evidently Andrew Myers [2], who is evidently a publicist for the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment, is just as gullible as the scribblers at Scientific American. He writes [2], “Adapting a sophisticated climate model, researchers show that there is plenty of wind available to supply half to several times the world’s total energy needs within the next two decades. “

To my knowledge, nobody has ever supposed that there was a shortage of wind energy. The problem has always been one of delivering steady power at a reasonable cost. Rather than help, wind makes the grid unstable when it supplies more than about 10% of the power on the grid at any moment.

Oh, and the wind can be weak over long periods of time. Scott MacNab writes in The Scotsman [3],

Electricity from wind power almost halved from 2,461 GW to 1,390 GW over the first two quarters of the year and was down more than 250 GWh year on year.

[1] From Ambrose Bierce’s Devil’s Dictionary…”Erudition: Dust shaken from a book into an empty skull.”

[2] It is not uncommon for students in elementary physics or chemistry classes to calculate the mass of a sodium atom and get something like 15.229387543821 kilograms, a quantity ridiculous for its size and its unwarranted precision. The usual defense is, “But that’s what my calculator said!”

In other words, for a full six months, Scottish wind power was down by half because the wind refused to blow on schedule. Oh, but that doesn’t matter, because the wind was probably pretty strong in the stratosphere or somewhere.

Robert Bryce, writing in The National Review [4], points out something that was unknown to me: Jacobson and Delucci published essentially the same stuff in the Proceedings of the National Academies:

The paper, which claimed to offer “a low-cost solution to the grid reliability problem” with 100 percent renewables, went on to win the Cozzarelli Prize, an annual award handed out by the National Academy. A Stanford website said that Jacobson’s paper was one of six chosen by “the editorial board of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences from the more than 3,000 research articles published in the journal in 2015.”

Perhaps Jacobson and Delucci meant to illustrate the low standards of the National Academies. In any case, Christopher Clack and 20 colleagues missed the humor, and took the intrepid Stanford scholars seriously enough to write a scathing rebuttal [5], and they published it in the very same Proceedings as the J&D paper.

Richard Heinberg of postcarbon.org [6] didn’t get the message that Jacobson writes Sokal-like spoofs. He has taken note of the recent Clack et al paper in National Academies Press and claimed that before too long, we could get 100% of our energy from renewable sources. He and David Fridley, staff scientist in the energy analysis program at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratories, write “A further challenge is that solar and wind yield electricity, but 80 percent of final energy is currently used in other forms—mostly as liquid and gaseous fuels.” So far, so good.

Heinberg goes on to say [6],

If, instead, the United States were to aim for an energy system, say, a tenth the size of its current one, then the transition would be far easier to fund and design. [Emphasis added]

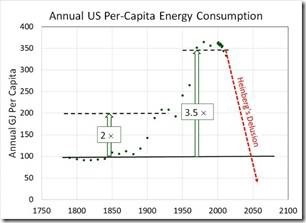

As a matter of fact, we use about 10,000 times as much energy as did our ancestors of 1700, and a mere factor of 10 seems small on that scale. However, most of the increase in consumption is due to the increase in population. On a per-capita basis, consumption has only grown by a factor of 3.5 over the same time period, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. US per-capita energy consumption. We now use 3.5 times as much energy per capita as our 1700s ancestors did. Heinberg thinks we can cut current consumption by a factor of 10.

Mr. Heinberg wants to decrease our energy consumption by a factor of ten, which would have us individually using about a third of what our ancestors used. If the population increases, the per-capita consumption might decrease to one-fourth, one fifth, or even a smaller fraction of that used by George Washington. His wish is shown in Figure 2. Good luck with that!

[1] Mark Z. Jacobson and Cristina Myers, “Saturation wind power potential and its implications for wind energy,” http://www.stanford.edu/group/efmh/jacobson/Articles/I/SatWindPot2012.pdf

[2] Andrew Myers, “Wind Could Meet Global Power Demand by 2030, September 10, 2012, http://woods.stanford.edu/news-events/news/wind-could-meet-global-power-demand-2030

[3] Scott MacNab, “Scotland ‘not windy enough’ for green power,” The Scotsman, 27 September 2012, p://www.scotsman.com/news/environment/scotland-not-windy-enough-for-green-power-1-2550478

[4] Robert Bryce, “The Appalling Delusion of 100 Percent Renewables, Exposed,” National Review, 6/24/17

[5] Christopher T. M. Clack et al, “Evaluation of a proposal for reliable low-cost grid power with 100% wind, water, and solar,” National Academies Press, June 27, 2017

[6] Richard Heinberg, “Controversy Explodes over Renewable Energy,” July 11, 2017, http://www.postcarbon.org/controversy-explodes-over-renewable-energy/ Heinberg’s CV (http://www.postcarbon.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/2016-RichardHeinberg-CV_2016-05-18.pdf) shows no educational credentials of any kind.

Advertisements Rate this:Share this: