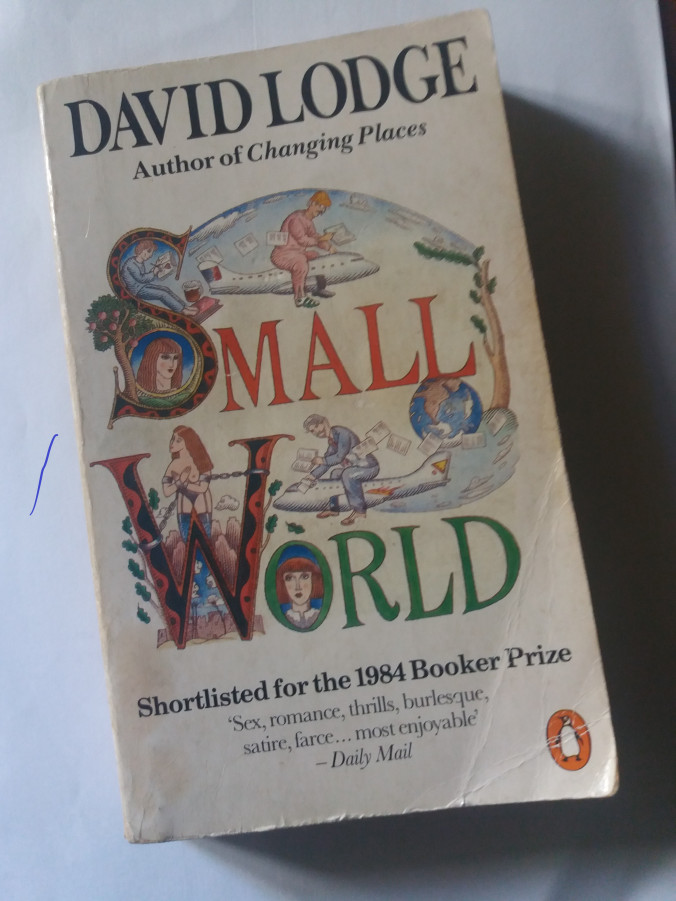

My September re-reading had to be from 1985, when the records state that I read 26 books, most of them novels. Although one of them was Middlemarch (well done, younger me), this looks like a year when I went for fairly recently published stuff, including two from the previous year’s Booker Prize shortlist: Julian Barnes’s Flaubert’s Parrot and Small World by David Lodge. (Neither of them won; they were beaten by Anita Brookner’s Hotel du Lac.) I decided on Small World because I’ve been a Lodge enthusiast for some time – and this particular book I remember as one of his most entertaining.

Small World is a kind of sequel to DL’s Changing Places (1975), which I read soon after it came out, and the characters of Philip Swallow and Morris Zapp, the first book’s memorable protagonists, are fairly central again, joined here by a much larger group of dramatis personae. But what I remember is that unlike Changing Places (and most of Lodge’s other fiction) Small World is – how shall I put this? – far-fetched. Despite its “realistic” surface, its plot is based on various Holy Grail quest legends and Spenser’s Fairie Queene (T.S.Eliot’s Waste Land also plays a part); like its models it is full of coincidences, long journeys, an innocent hero and an elusive heroine. It nevertheless fits into the “campus novel” genre, and is structured around a series of international academic conferences about literature. This makes it sound rather forbidding: but it has proved enjoyable even on a second reading.

In fact I may have got more out of Small World – subtitle “An Academic Romance” – this time, as since my first reading my life has got closer to academia. Admittedly, in 1985 Clever Wife was nearing the end of a PhD, but I didn’t know much about the academic world. Now, having worked as a journalist-cum-publicist at a US university in the 1990s, later freelancing for a higher education weekly and doing quite a lot of academic copyediting, I feel more clued up (though I am still an amateur when it comes to English literature: I don’t even have an A-level in the subject).

Although Small World is fun to read, I feel that, more than any other of Lodge’s novels, it’s designed to be the subject of learned academic exegesis. Sure enough, you can find essays such as “Quest and Conquest in the Fiction of David Lodge” and “The Reader as Discoverer in David Lodge’s Small World” online, and the novel has also been quoted in some philosophical literature. Here’s Peter Lamarque and Stein Haugom Olsen’s Truth, Fiction and Literature: A Philosophical Perspective, which I happen to have borrowed recently: in a chapter on “The Theory of Novelistic Truth” they quote Small World‘s “Author’s note”. In this, before pointing to some unlikely things in the book that “really” exist – “an underground chapel at Heathrow and a James Joyce pub in Zurich” for instance – Lodge states that his novel “resembles what is sometimes called the real world, without corresponding exactly to it, and it is peopled by figments of the imagination”. This is rather like the note at the start of Lodge’s Changing Places: “Rummidge and Euphoria [where much of the novel’s action takes place] are places on the map of a comic world which resembles the one we are standing on without corresponding to it”. Such disclaimers, Lamarque and Olsen write, “implicitly make the claim that [the author’s] work is of a type that naturally can be construed as presenting truths about particular historical events or personages. For the very act of issuing a denial presupposes that there is something that needs to be denied.”

I could digress at some length about novelistic truth, but I’ll save such philosophical ramblings for another time. Meanwhile, some further random observations about Small World:

1. I don’t think I’d noticed this before, but Lodge’s narrative switches between present and past tenses frequently. While some readers (and writers) dislike the use of the narrative present, I feel it can add some urgency – which seems to be why DL uses it. For example he jumps rapidly from one character to another at the beginning of Part II to describe more or less simultaneous events in England, Australia, New Hampshire, Chicago, Berlin, Tokyo, Turkey and elsewhere (is this an echo of the “Wandering Rocks” episode of Ulysses?). Sample: “In Paris, as in Berlin, it is 7.30. … In the high-ceilinged bedroom of an elegant apartment on the Boulevard Huysmans, the telephone rings beside the double bed. Without opening his eyes, hooded like a lizard’s in the brown leathery face, Michel Tardieu, Professor of Narratology in the Sorbonne, extends a bare arm from beneath his duvet …” (p.97 in my edition).

2. Perhaps inevitably, some of the novel has dated. Here’s Morris Zapp talking about the “global campus” in Chapter 1: “There are three things which have revolutionized academic life in the last twenty years, though very few people have woken up to the fact: jet travel, direct-dialling telephones and the Xerox machine” (p. 43). In 1984, the Internet was still a few years away.

3. Yes, there’s a lot of air travel in Small World. And we are reminded that in the 1980s, long before Al-Qaeda was a threat, airport security was already a hassle: “He joins a long line of people shuffling through the security checkpoint. His handbaggage is opened and searched. Practised fingers turn over the jumble of toiletries, medicines, cigars, spare socks … Few privacies are vouchsafed to the modern traveller” (p.102).

4. Maybe it’s a bit too long, though – 339 pages in my paperback, compared to Changing Places’s 251. The kidnapping that occurs in Part IV doesn’t seem necessary to the plot, for instance. Does it correspond to an incident in The Faerie Queene or some other romance?

5. I rather like the cover to my 1985 paperback (below), which is by Ian Beck, and has the merit of suggesting that the artist has actually read the book. (You can see more of Beck’s work at https://ianbeck.wordpress.com/, where I’m reminded he used to do illustrations for Radio Times, and at least one cover – for the 1987 Proms issue.)

Also read in September, two Brits and one American: Down and Out in Paris and London (something I should have read years ago); P.G. Wodehouse’s Doctor Sally (lightweight even by Wodehouse’s standards); and You Don’t Have to Live Like This by Benjamin Markovits (who’d have thought a novel about urban redevelopment in Detroit would be such a page-turner?). Plus some chapters of Tim Parks’s Where I’m Reading From – stimulating thoughts relevant to this blog …

Share this: