Yes (I see inquisitive phantom stares), I listened to an audiobook written in this decade. And it was good. Very good. Brilliant actually. As it was an audiobook, I’m unable to write an in-depth review. However there are plenty online for the curious–in part because it won the 2015 Nebula Award. I added two additional novels that have been waiting patiently in a “to review” pile that are more my standard territory…

Think of these short reviews as tantalizing fragments rather than my normal analysis. The books that reside in these short review posts often defeated my reviewing capabilities.

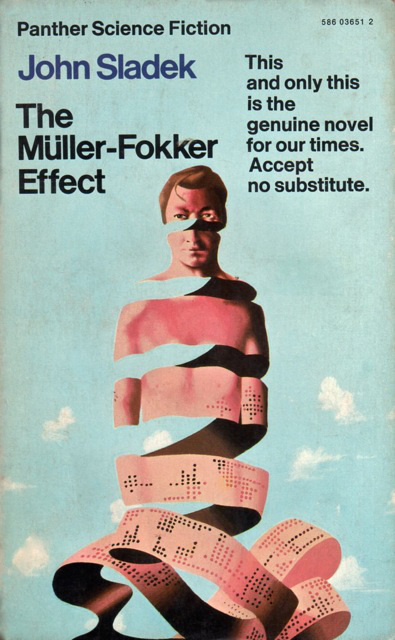

1. The Müller-Fokker Effect, John Sladek (1970)

(McInnery’s cover for the 1972 edition)

4.25/5 (Very Good)

In my 2016 in review I promised to read more of Sladek’s work, and for once I’m holding true to my reading goals.

That said, I find Sladek’s novels notoriously difficult to parse into cohesive reviews—his SF (and my reviews by extension) stretch satirically in all directions, unfolding in fascinating experiments that jest with layered wordplay and (often) diagrammatic dalliances (see example below). There’s a humorous indulgence in his work you have buy into that rewards the diligent.

Far superior to Mechasm (variant title: The Reproductive System) (1968), The Müller-Fokker Effect tells the story of Bob, “a technical writer with a BA in English” recently terminated by “National Arsenamid” (9) and his position replaced by a computer… At home his son “worships the SS” and desperately wants to attend military school (12). Sladek’s novel takes the form of mass immersion into the madcap world of rising fascism, bureaucratic ineptitude, and rampant technological transformation. The narrative strands tangle and interrelate and plunge the reader into a manic journey as Bob’s transformed into computer code in an experiment gone awry and attempts to understand his new world. Side-characters give us glimpses into the psychological landscape of this future. The masculine and irresistible Glen Dale, a cypher for Hugh Hefner, carefully shepherded by those who oversee his business (built upon his desirability and bachelor status) cannot form lasting relationships, or even sexual relationships, with women. Societal expectations, the influence of media, and the inability to assess the impact of technology form the work’s central themes.

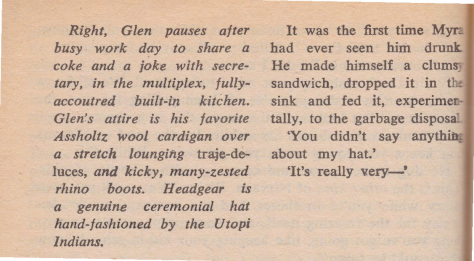

Sladek’s most successful at world emersion—analysis and comparison with Brunner’s techniques in Stand on Zanzibar (1968) would be a fascinating project. And the book’s relentlessly funny…. Dale’s experiences in his penthouse are often told in parallel columns. One column relates he’ll be presented to devoted readers, the second column his “real” life (126):

In many ways The Müller-Fokker Effect belongs back on the “to read” pile, for a slower time, for a weekend pondering its mysteries. A methodical reread is needed suss out the computerized giggles and metafictional hilarities.

Recommended for fans of New Wave SF.

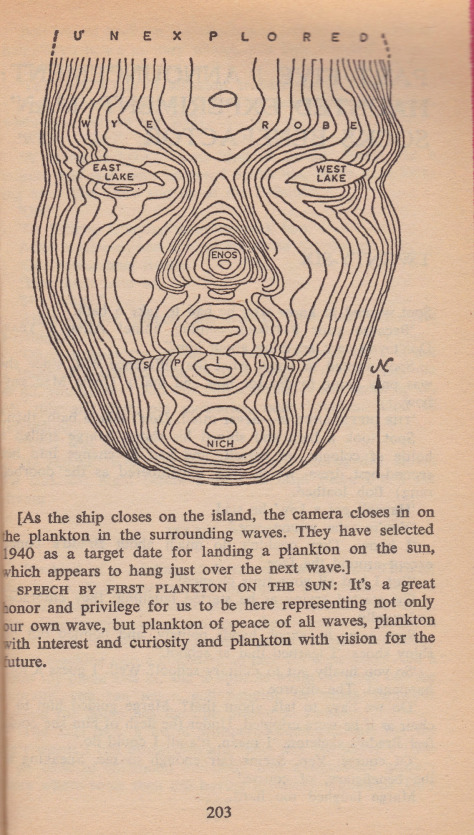

The human body as computerized geography….

If you’re curious about John Sladek’s views on genre and his own writing see this interview with David Langford. I find a few passages especially humorous/revealing:

1) Langford reminisces about asking a “partially-deaf librarian” for a copy of the book and resulting horror (due to the title) and Sladek quips: “Young persons have no business reading such a book, which contains sex, violence and anagrams.”

2) As to why Sladek writes science fiction, he responds: “Science fiction is one way of making sense out of a senseless world. I think people are often bewildered by the world they find themselves in […].” Sladek’s positioning of SF as rooted firmly in present exegesis resonates rather than some half-baked claim of prescience or foretelling a future potentiality.

And more along this same theme of the dangers (and errors) of SF as predictive:

“Of course, that leads people into the error of believing that SF has all the answers, that it’s prescriptive or predictive. They want to use it to get a peek at the way the world really will be or really ought to be. Very dangerous, because the predictions of SF are almost always too simple-minded. It’s not futurology – though futurology is too simple-minded too – and it’s not a recipe book for cooking up tomorrows.”

~

2. Options, Robert Sheckley (1975)

(Ron Waltosky’s cover for the 1975 edition)

3.5/5 (Good)

Robert Sheckley’s short stories have long been some of my favorite satires and (often) whimsical allegories of the 1950s/60s. The best of his I’ve reviewed so far include Store of Infinity (1960), Citizen in Space (1955) and his novel Journey Beyond Tomorrow (1962).

Options (1975) formed the vanguard of my attempt to move into his later (substantial) 70s oeuvre. Although technically adept and dabbling in my favorite type of narratological metafiction, Options did not sit entirely well with me–and as I am still unable to put my finger on exactly why I put off the review for months. A novel about narrative, Sheckley creates the most preposterous narrative possible, and as it no longer can more forward on its own power must interject himself into the story to fix the morass he’s created.

The novel begins with a notice:

“The rules of normalcy will be temporarily suspended while new rules are being drawn. The new rules may not be the same as the old rules. No hints can be given concerning the new rules. The best thing to do might be to avoid conflicting situations, spend the rest of the day in bed, cool out. Or, if that sounds boring, I could take you for a ride” (11).

What followers are 77 short chapters that follow the misadventures of Tom Mishkin who crashes on the planet Harmonia. He most journey across the surface with a robot programmed for an entirely different landscape in order to find a parts stash to fix his ship. Mad synesthesiasts, multi-headed worms, self-loathing raemits, and other bizarre creatures encounter Tom at every turn. Sheckley’s shines forth on every page: a tour of an imaginary castle results in a discussion of the effects of imaginary food, “among the ignorant and gullible, for example, imaginary foods tend to be quite nourishing. Pseudo-nourishing, of course, but the nervous system cannot differentiate between real and imaginary events” (52).

Perhaps my frustration derives from an inability to ascertain what precisely about narrative Sheckley wishes to exposure other than its sheer artificiality… And if that’s the case, then what better way to demonstrate sheer artificiality than state that there are no rules. But “novel” without rules has the side-effect of abandoning the reader somewhere along the journey. It’s a virtuosic display that reads in many ways as a series of 77 micro-stories, each with their own punch line.

I still recommend the book for fans of Sheckley and New Wave SF.

(Karel Thole’s cover for the 1976 edition)

(Uncredited cover for the 1977 edition)

~

3. Annihilation, Jeff VanderMeer (2014)

(Eric Nyquist’s cover for the 2014 edition)

5/5 (Masterpiece)

Won the 2015 Nebula Award.

Jeff VanderMeer is not a new author to me—as a fan of fantasy in my youth I devoured the Ambergris sequence: the stories and text fragments of the world collected in Cities of Saints and Madmen (2001) and explored with additional rigor in his fungal nightmare of a novel Shriek: An Afterword (2006). Both in hindsight, were bogged down by pseudo-Victorian stylings and forced their premises somewhat imprecisely (harsh perhaps, I’m open to arguments to the contrary)… But the fantastic dreariness of the world of Ambergris, the odd growths and peeling paint, the spectacle and mysteries, the historian characters and intertextual references fascinated and inspired me…

…and Annihilation takes everything wonderful about the Ambergris tales and distills it down to a taught and terrifying unity. The obsession with memory and recall, and hidden traumas, and fungi in all forms (on walls, repurposing bodies, metaphoric decay) finds perfect vehicle in a world that could be ours but for a few common referents that have been switched around. The story follows an anthropologist, surveyor, psychologist, and biologist and their bizarre journey into a transformed landscape called Area X. The entire book is told from the perspective of the biologist. VanderMeer deftly utilizes the diaristic form and all the notions bundled up in recording one’s activities—hiding pasts, traumas surfacing after particular events, etc. These reveals, although key for propelling the narrative forward, feel organic and “real.”

I do not plan on reading the sequels in the Southern Reach trilogy. I rather the character arc of the biologist reside, content, in mind rather than learn the particulars of Area X. I am afraid the explanation will overwhelm the human drama that forms its emotional and conceptual core. VanderMeer slims down his prose and creates a harrowing vision about the power of memory and the reasons why we explore and put ourselves in unbelievable danger.

Highly Recommended.

(Marion Blomeyer’s cover for the 2014 German edition)

For more book reviews consult the INDEX

Share this: