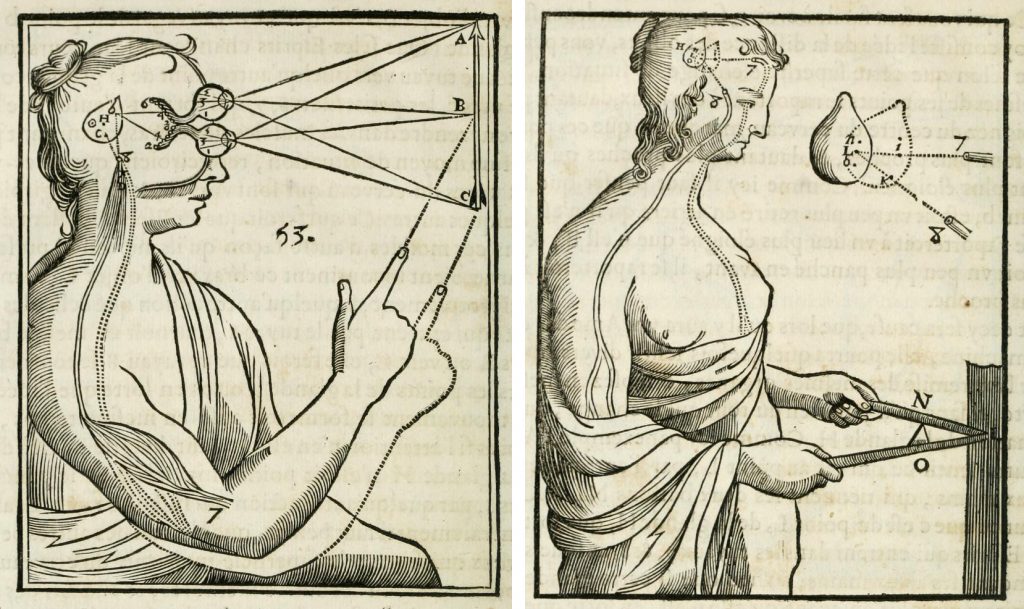

It is a strange fact that our experience isn’t body-shaped. If it can be said to have a shape at all (which it can’t), it is an ill-defined blob shifting with each slight movement of ours. Even though we are constantly receiving sensory input from each inch of our skin, somehow these data do not sum to a person-shaped field of sensation in our unified consciousness. Likewise, our visual field is not clean or shapely (in the very literal sense of “shape-like”). Sometimes we visualize our visual field as a circular vignette, blurry around the edges and then neatly fading into blackness. Of course our peripherals aren’t blurrier per se (and what’s outside them isn’t black either), rather they are just less present to our minds, in some sense that is as difficult to describe as color to the colorblind. These descriptive difficulties are somewhat disturbing, but maybe the fact that we don’t have entirely accurate models of our mode of grasping is not all that surprising. The models themselves need to be grasped, and so we come up against either the brute fact that we can successfully grasp certain things, or infinite regress. In epistemology, these two alternatives correspond somewhat roughly to the “externalist” and “internalist” positions, as regards justification.

EXT: Justification may depend on factors external to the subject.

INT: Justification only depends on what is internal to the subject.

I would argue that the “external” / “internal” distinction (as well as the previous talk of grasping) must boil down to accessibility to the subject. If there is something “produced by” the agent, or even quite literally inside the agent’s skull, and yet not directly accessible to her (for example a Freudian subconscious structure, or simpler, the firing of a neuron) it might as well be “outside.”

For the internalist about justification, there is a regress. One internalist picture of justification for belief that p would require that the subject know (have access to the fact that) the method of belief formation M that she employed in this case reliably forms true beliefs. But if this knowledge of reliability requires it’s own justification, the subject will need to know that her method (M’) for coming to believe that M is reliable itself reliably produces true beliefs, and so on. For the externalist on the other hand, the subject is justified in believing p just because her method M does in fact reliably produce true beliefs, even if the reliability itself is not verifiable by the subject without leading to regress. For similar reasons the externalist also has an easier time explaining how young children who do not possess any higher-order knowledge or much inductive evidence about the reliability of their methods of belief formation can, for example, know there is a cup on the table by simple perception.

Ultimately, however, the externalist picture starts to seem inadequate as well, since it flattens any normative edge the concept of justification (and potentially the concept of knowledge as well) might have otherwise had. It is natural to think of justification as the norm of belief, i.e. if S is justified in believing p, then S ought believe p (assuming there are no non-cognitive/practical reasons to not believe p that defeat the cognitive/epistemic reasons in the belief’s favor). But if the epistemic agent S does not have access to her justification for p, which is just a fact about her belief that p standing in the right kind of relation to the state of affairs that p, then it would seem less appealing to use justification or lack thereof as a reason for praising or condemning S’s coming to belief P. These considerations form something like an instance of an ought-implies-can argument:

Some externalists may feel pressure to simply bite the conclusion of this argument, however, a clever externalist might claim that there are just two senses of “justification” floating around in our natural language, one normative, call it “ought-to-believe-ness” and one descriptive, call it “reliability.” While in most cases, these two notions are in agreement, they can come apart in some cases: precisely those cases in which the epistemic agent is cut off from any access to the reliability of her own method of belief formation.

Consider one extreme case: blindsight. In split-brain patients and in some cases of otherwise complete blindness there is a phenomenon in which the patient will vigorously insist that she sees nothing, and has no idea where some named object is, but when she is told to guess and point or reach out to it, she will succeed most or all of the time. The neuroscience behind this is a secondary visual pathway that is not as integrated with other brain systems like the ones that control language and propositional beliefs. Here we have a case in which the agent, given all the info and evidence she has access to, ought not believe that she can successfully point to the object[1] (assuming she doesn’t have inductive evidence from previous times she was able to point to things successfully), however the process she employs to come to the true belief that “the object is right there” is actually reliable, even though subjectively it feels like the process is just guessing. The assessment that this belief has reliability but not ought-to-believe-ness seems to align with our intuitions about the case well enough.

We might then think that all that is left is an empirical dispute about natural language: in what contexts and to what degrees do people use “justification” to mean something like “ought-to-believe-ness” vs. something like reliability? And if we take justification to be a necessary component of knowledge, then we might consider a similar semantic distinction with regard to ascriptions of knowledge. Again consider the blindsighter. Surely there is a somewhat natural sense of “knows” for which “the blindsighter knows where x is” is true, (the same sense in which we speak of people knowing things unconsciously). For this sense of “knows”, the blindsighter’s denial that she can successfully point to the target object would be explained as a lack of 2nd-order knowledge: she doesn’t know that she knows. The 1st-order belief formation process is reliable, however the 2nd-order process forms a false belief about the 1st-order process, that it is not reliable, and so clearly fails to be reliable itself. However, there is another sense of “knows” for which the blindsighter lacks knowledge of where the target object is. We may call this the strict sense, or the normative sense (because of its connection with the ought-to-believe version of justification).

This distinction in knowledge and justification at least seems to explain many of the differences in use of knowledge-terms between internalist and externalist epistemologists. The question still remains, however, of whether there are any “real things” that correspond to either the “Reliablist” or the “Deontological” versions of knowledge-talk. How might this get settled? Which notions of justification get metaphysically “reified” seems to depend on other realist/anti-realist debates: the Reliablist notion perhaps depending on modal realism (if reliability must be cashed out in terms of counterfactuals) and the Deontological notions depending on moral realism. But these debates in turn are difficult to frame in any other terms that the conditions for correct and incorrect use of the terms of the domain (e.g. ethics or modality), the anti-realist often taking the side that there are certain sentences (sometimes all sentences) of the domain in consideration for which the correctness (or truth) of their use is indeterminate.

So focusing on our use of the terms, rather than the metaphysical status of their objects, we can ask the following: Is there anything that could warrant scraping one of these uses of knowledge-talk for the other (or in an extreme case rejecting both)? And if the answer to the previous question is yes, what would it look like and why would it warrant such serious revision?

Michael Dummett has some useful reflections on what sorts of things might motivate revisionism even given a use-theory-of-meaning:

“It might seem an approach to meaning which regarded it as exhaustively determined by use would rule out any form of revisionism. If use constitutes meaning, then, it might seem, use is beyond criticism: there can be no place for rejecting any established mathematical practice, such as the use of certain forms of argument or modes of proof, since that practice, together with all others which are generally accepted, is simply constitutive of the meanings of our mathematical statements, and we surely have the right to make our statements mean whatever we choose they shall mean. Such an attitude is one possible development of the thesis that use exhaustively determines meaning: it is, however, one which can, ultimately, be supported only by the adoption of a holistic view of language. On such a view, it is illegitimate to ask after the content of any single statement…there is no adequate way of understanding the statement short of knowing the entire language…it is not that a statement or even a theory has, as it were, a primal meaning which then gets modified by the interconnections that are established with other statements and other theories; rather, its meaning simply consists in the place which it occupies in the complicated network that constitutes the totality of our linguistic practices…” (The Philosophical Bases of Intuitionistic Logic)

So if we are to revise our use of “justification”, we do so by rejecting this semantic holism, and insisting that particular statements about an agent’s justification or lack thereof must have determinate individual content. For instance, we insist that for any given statement about justification, there is something real in the world that we are trying to identify. But while we may reject semantic holism, we also might accept a more restricted local holism, in which ascriptions of justification are legitimately modified by other concepts like knowledge, ought-to-believeness, and reliability, e.g. we might use “justification” as the label for the property of a true belief that is in normal cases sufficient for the belief to be legitimately called “knowledge”. On this understanding, the meaning/use of “justification” is parasitic on that of “knowledge”. Or perhaps they are interdefined.

This local holism is the antirealist challenge to epistemology’s traditional analyses of concepts like knowledge and justification, insofar as these analyses claim to show that there is a unique extralinguistic entity corresponding to, e.g. “justification”. In response to this challenge, it is crucial to consider how knowledge-talk is meaningfully related to other “semantic clusters” e.g. the normative realm of value/obligation, the theoretical realm of reliable causal processes, and the empirical realm of what Quine called observation sentences. The locally holistic model of meaning shows us that neither is it impossible for us to revise our epistemic concepts in a principled way, nor is it possible to find an Archimedean point on which to ground all our concepts, like a certain self-evident theory of epistemic justification. The project of integrated epistemology is to develop a picture in which the holistic clusters cohere with each other as much as possible (and no cluster remains floating, disconnected from the rest of our reality), whether the clusters are highly abstract (like the concepts of epistemology itself, so general as to even come under their own purview) or highly concrete (like the fact that I have hands).

[1] There is a sense of “ought” for which we would say the blindsighter ought to believe that she can successfully point to the object. This is the familiar distinction between internal reasons (those “possessed by” the agent) and external reasons. External reasons seem to constitute a form of normativity that violates the ought-implies-can principle, but it is tempting to say that they are only reasons at all insofar as an agent could acquire them. If this analysis is correct then we can claim some minimal progress, since the question of whether or not we should be realists about external reasons may reduce to the question of whether we should be modal realists, which I am not inclined to delve into here.

Advertisements Share this: