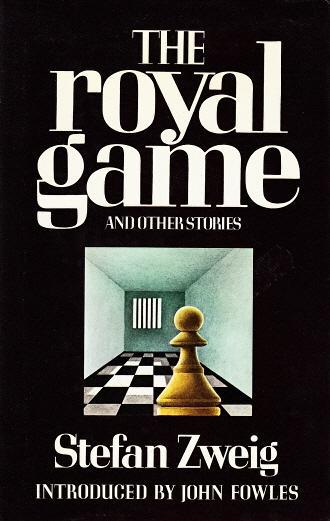

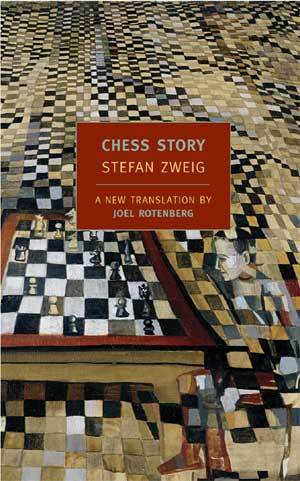

The novella Schachnovelle (which means ”The Royal Game,” a label for chess), the last fiction written by once internationally renowned and best-selling Austrian Jewish biographer and novelist Stefan Zweig (1881-1942) has been reprinted in English as The Chess Game by the New York Review Books. Zweig had gotten out of his beloved Vienna in 1934, shortly after Hitler came to power in Germany and before Austria was annexed in the Third Reich. In 1940 he and his new wife (heretofore secretary) the much younger Lotte Altmann moved on to New York City and then to Petropolis in Brazil, where they committed suicide (by veronal (a barbiturate) overdose) on February 23, 1942.

The Royal Game/Chess Story is the only fiction by Zweig to include any notice of the Nazi reign of terror. Its victim in the book, Dr. B., is not Jewish but is a banker like Zweig’s mother’s family, and a royalist, though it is not clear to me whether of the Hapsburgs (in Austria) or Hohenzollern (Prussian-German) royal house deposed by defeat in the First World War. His family has also discreetly managed to get many of the assets of Roman Catholic institutions beyond reach of Nazi expropriation.

Though not physically brutalized by the Gestapo — more interested in finding and seizing wealth than in punishing those loyal to vanished empires, Dr. B. was driven crazy by being kept in solitary confinement when not being interrogated. He managed to steal a book that laid out 150 classic chess matches and honed his chess skills by repeating them over and over and then starting to play himself: a black self and a white self that could not know what the other was thinking in the way of chess strategy (schizogenesis).

Dr. B. does not appear until nearly midway through the book. He tells his story to a curious traveler on the same slow boat to South America as the narrator, who had been trying to meet and assess the reigning world chess champion, Mirko Czentovic, a Slavic peasant who was illiterate and slow-witted, but had a talent for chess. (Czentovic is a kind of idiot savant and, perhaps, a metaphor for mindless battling of Hitler’s army, except that he is Slavic rather than “Aryan.)

A rich American chess aficionado named McConnor (a Scottish engineer who had gotten rich in California) wants to see a grand mater in action and for a fee of $250 (that’s 1941 dollars!) engages the master to play multiple simultaneous games. There is only one chessboard on the ship and Czentovic instead plays a committee. He is about to win a second game, when a bystander (Dr. B) starts offering advise that brings the game to a draw.

Dr. B has not physically played chess since he was a schoolboy, decades earlier, and does not know how he will perform in public (though he has impressed. Czentovic and the kibitzers as a sort of chess-playing ventriloquist). Thinking each side’s moves many moves in advance, Czentrovic taking the full allotment of ten minutes before each move (even the first one in the second game) is torture for Dr. B.

Herman Hesse was dismayed that only the pain and suffering of his 1927 novel Steppenwolf seemed to be noticed by readers, not the hope of redemption in the book. It seems to me the same despondent reading of Chess Story has been prevalent, in part in the shadow of the despair with the destruction of his civilization that drove Zweig to suicide after sending off the manuscript. (Why I am reading writers in German of much fame between the world wars now, I don’t know. The times here seemed more analogous to the late-1930s and early-1940s to me during the mid-2000s, when I was reading many stories about collaboration.)

The NYR edition includes an appreciative introduction by the distinguished Yale University historian (born in Berlin in 1923, got out in 1939), Peter Gay (The Pulitzer Prize-winning The Enlightenment; plus Mozart, Weimar Culture, Schnitzler’s Century, My German Question, and many books) I think it reveals too much of the plot of the slender volume and should be read after rather than before Zweig’s text, though the first part about Zweig provides a good introduction to the author, whose works revived by New York Review books so far include Confusion, The Post-Office Girl, Journey into the Past, and Beware of Pity.

©2014, Stephen O. Murray

Advertisements Share this: