CUL, Mac Pro, OS X, 10.6.8, Phase One P40, Capture One 7.1, Profoto Strobes, Schneider 80mm LS /f2.8, ColorChecker

CUL, Mac Pro, OS X, 10.6.8, Phase One P40, Capture One 7.1, Profoto Strobes, Schneider 80mm LS /f2.8, ColorChecker

Andrew Davidson’s The Gargoyle (Random House, 2008) is a fast-moving, smooth-reading, deceptively happy-ending narration. Taking cues from Dante Alighieri’s Inferno, medieval Italian, Japanese, and Icelandic tales of love, Davidson spins a post-modern tale set in unspecified contemporary North American city, interweaving episodes of gothic and romance literature with present-day scientific knowledge about the effects of burns, schizophrenia, as well as background histories of the major characters.

The novel offers numerous thematic elements whose prominence clearly emerges from the narration: everlasting true love even beyond the unexpected and bitter end, search for encyclopedic knowledge, life with cocaine and morphine dependency (the “snake”), artistic raptures, questions about actions and their earthly and after-life consequences, metempsychosis, need for continuity of human affairs through talismans and special objects. All of these add something particular to the plot. Having grown up with drug-addicted foster parents, taking advantage of the library to quench his thirst for knowledge, and, later, on account of his good looks and lack of other skills, becoming a porn actor and director: all of these suddenly turn inconsequential thanks to one fateful Good Friday when he is about thirty years old (obvious echoes of Dante). He has a near-fatal car accident in which he is horribly burned (the gory details are spelled out in full) and deprived of his work tool, so to speak. Ending up in a hospital, he contemplates committing suicide as soon as he is released: his disfigurement, his lack of sexual organ, the loss of his livelihood and his film company mean that there is nothing left for him to do but end it all. The narration follows him in his hospital bed; he is taken care of conscientious doctors and nurses, and one uninvited character, Marianne Engel, the anchor which steadies the path of the narration. She claims to have met the protagonist before (about 700 years before) and to have loved him then. At that time she worked in the Engelthal monastery as a scribe; he was a condottiero brought to the sisters since he was horribly burned. Marianne cures him now as she did then, and she keeps being in love with him through the centuries and now. At the hospital, Marianne’s tales of medieval romantic love, her artistic energy, kind disposition, nutritious food, make him abandon his desire to die. Once he is discharged, she takes him into her gothic-looking house, keeps taking care of him, and secures his future. She sculpts for a living: her grotesque stone sculptures resemble the strange medieval decorations on churches: gargoyles. She also starts to sculpt the protagonist. Her artistic pursuit is spurred on by three special characters from her medieval life who assure her that she only has 27 more “hearts” to sculpt and then her last heart is to be given to her true love and let free. Having finished these “hearts”, she walks off into the sea never to be found again. Our protagonist passes his life writing his story.

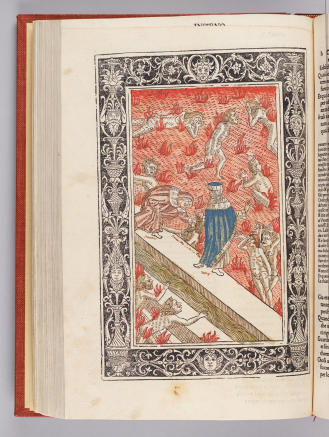

The word “inferno” conjures images of raging fire burning the damned who deserve to be punished, because, in the Catholic tradition, they transgressed specific interdictions and rules. Our nameless protagonist is not a believer and therefore he does not explain his predicament as a just retribution for his previous drug-filled debauched life. In the novel, the role of Dante’s voyage through hell is only superficial: the protagonist has entered a hellish type of life, and he tries to understand it. He too has a Virgil: it is Marianne who leads him – through narration of love stories – to forget about his disfigured existence. There is no Beatrice, though, to lead him to God. Our protagonist lives his new post-burned life simply as a spectator: unlike Dante who cries and is moved by the fate of the damned, he is not stirred by what happens around him, he does not seem to feel any gratitude to Marianne, or in fact even love. He is simply with her. His pre-accident life was full of sex but devoid of love, full of drugs and alcohol but no moral signposts, no ethical concerns, no real friends, no real parents. He did not have healthy feelings of self-love or self-worth, but he demonstrated lots of vanity. The novel is a loud yearning cry for something to hold on to, something that would explain the consequences of one’s actions much like the deserved punishments of the damned in Dante’s Inferno. Alighieri’s epic poem, for a non-believer like the protagonist, is simply an imaginative tale, full of gory details; the connection between the literary work and the society that created it and the human stories underpinned by biblical teachings, philosophical works, scientific observations is totally lost. This is perhaps the significance of The Gargoyle: the protagonist’s cynical attitude of detached observer allows him the only activity that has a semblance of pleasure, that of reading anything and everything. However, this does not make him a wise man.

Every author inevitably toys with his/her readers. It is disconcerting, however, when the protagonist/author is cynically flippant about his readers, as is the case in The Gargoyle. This talking down to the reader happens also at special moments in the story, and it completely destroys the rich imagery that the reader was about to construct. Here are two examples:

“I have no idea whether beginning with my accident was the best decision, as I’ve never written a book before. Truth be told, I started with the crash because I wanted to catch your interest and drag you into the story. You’re still reading, so it seems to have worked”. (p. 5)

In the middle of a long list of food items, he says “…guglielmo marconi (just checking to see if you’re still reading)” (p. 167.)

This meta-narrative ploy is not new, moreover, it too accentuates the novel’s postmodern construction.

In conclusion, the muddle created by juxtaposing the past and the present, religious and secular images, imaginative tales and scientific descriptions of medical conditions perfectly illustrates the post-modern emptiness which underlies the result of the attitude “anything goes”. However, the nihilistic condition seems to drain out the protagonist completely, and he stands out as a disfigured empty shell whose only real companion is a dog and whose only activity is writing. The sole effigies with a “heart” remain the heavy stone gargoyles, creations of an exalted artist.

*The top-right illustration comes from the 1487 edition of the Commedia; printer: Boninus de Boninis (https://www.frizzifrizzi.it/2017/11/10/tesori-darchivio-alcune-le-prime-edizioni-illustrate-della-divina-commedia-state-digitalizzate/).

Advertisements Share this: